How Pity Informs Our Political Views

Featured image: Joker (2019) is an origin story which follows the troubled life of Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix). The narrative is suggestive of Fleck being driven by external factors to the brink of insanity: made socially and economically vulnerable by poverty, an abnormal family life, and inadequate mental health support; kicked down and mistreated many times by his colleagues and strangers; a failed comedian and a loner who wants to be felt—seen and loved—but just isn't. He searches for validation. Amidst a decaying Gotham City and a crumbling personal life, he dreams of leading a counter-cultural revolution against the rich and the powerful, committing heinous crimes as his alter-ego, 'the Joker' (scenes which sparked a media backlash in real life for potentially inspiring 'incels'). How much moral responsibility we alleviate from Fleck for his wickedness depends on how much we perceive him as a victim, whereby those politically on the left tend to be more charitable with their pity. (Niko Tavernise/The Associated Press)

noun

/'pɪt.i/

the feeling of sorrow and compassion caused by the sufferings and misfortunes of others.

Someone may be living in poverty. They could be suffering from stress, anxiety, or trauma. They could be addicted to a substance such as alcohol, nicotine, or methamphetamine. They could just be unlucky in having the dispositions they have coupled with their upbringing. Yet we may not see them as a victim at all but an enabler of their own suffering. Or we might consider them a victim of their circumstances; so we cut them slack with our judgements.

Politically, we each draw a line at which we believe someone should take personal responsibility for themselves. This line is subjective but tends to be drawn at the point at which we believe the individual overly relies on or exploits the systems and people around them.

Pity or pity’s absence, then, sits at the hearts of our convictions, determining whether we feel sorry for or are left frustrated by people’s behaviours. But the million-dollar question is this: when do we offer ‘too much’ pity? For the state must pass the buck back to its citizens somewhere by saying: ‘Look, you have to sort this out for yourselves now. Only you can take control of your situations.’

From left to right, our answers reveal deep divisions.

I. Politics

Political views shape the laws which determine the boundaries of personal responsibility. But it’s not the ends we disagree on: it’s the means.

A common end goal, across all political ideologies, is for people to be autonomous from external forces: we want people to flourish independently, not be fecklessly stuck in ruts without reachable escape routes. Certain governmental support should be available (only) when people genuinely require. Of course, this is where we diverge: when does someone ‘genuinely require’ help? Our beliefs on this particular point, I hypothesise, are founded on how much agency we assume people have.

Many people want to get themselves out of problematic situations and are even proactive in the first instance but later fail because the support systems aren’t in place to sustain their motivations and supply them with opportunities to navigate their ways out.

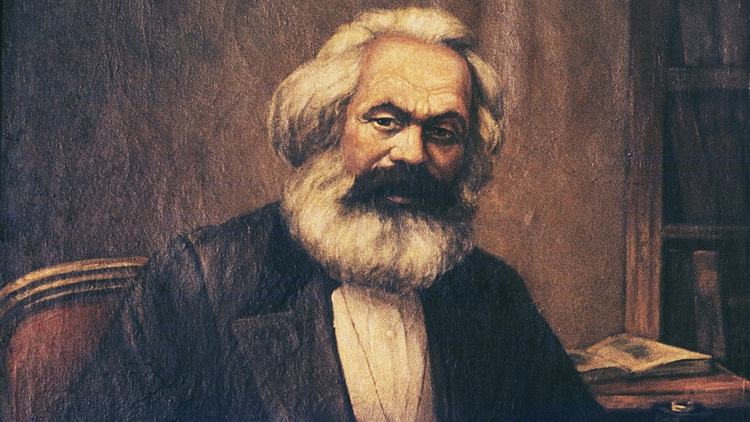

Karl Marx (pictured) accepted Hegel's view that divisions have been historically driven by material conditions in society (e.g. of wealth). Humans, Marx claimed, were isolated, egoistic beings who impeded each other. But their selfishness arose from the fight for scarce resources, which capitalism exacerbates, not human nature. Adding rights would not do enough to provide people with adequate freedoms for a good life. Instead, Marx asked us to welcome community ideals, whereby the 'real, individual man resumes the abstract citizen into himself and as an individual man has become a species-being' (On the Jewish Question). His communism stipulates state ownership of the means of production, where each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs—i.e. we need a symbiotic relationship between a big state and its citizens. (ullsteinbild)

Those on the left of the political spectrum tend to believe people, particularly the poor and the oppressed, lack the means to flourish without state interventions. They, therefore, tend to support relatively high tax rates and well-funded public services (e.g. schools, hospitals, mental health services, etc., as paid for by taxes) to rectify inequalities caused by humans being humans across their specific cultural contexts. They assume that, when the state is absent to redistribute resources (e.g. through unemployment benefits, greater government spending to create jobs better state-funded education, state-incentivised house-building), people will inhibit each other from fairly earning good standards of living.

Those on the right tend to place greater trust in people’s individual judgement. In a society of entrusted individuals (e.g. in line with libertarianism) people provide themselves with good standards of living. Resources will fairly distribute themselves through the merit of skill and hard work: people will find jobs, they will meet their needs through the property they acquire and their disposable income, and be happy—they will earn their living. They, therefore, tend to support a small state which is restricted to legislative matters, sets low taxes, and encourages free-flowing private enterprise (e.g. laissez-faire economics). The state meddling in human affairs enmeshes people in modes of dependency by pampering them. There are opportunity costs to this, too: money from state-legislated provisions and programmes could be put to better use—say, towards public security, legal representation, measures to fight climate change, and so forth.

Do people choose to be poor? If they do, why should we pity them for the conditions they live in? This opens up a complex debate. Arguably, money is a resource that buys one more freedoms unfairly (see: G.A. Cohen) and the rich can have many more opportunities to stay out of poverty. Take Terry Pratchett's 'Boots' theory: expensive boots last longer and save the buyer more money in the long term. The same is true for fancy washing machines and reliable cars. Thus there is a strong sense of socioeconomic unfairness in how wealth is divided amongst us since the poor don't have the same luxuries, let alone access to more-modest opportunities, such as affordable apprenticeships and places to study in higher education without working and incurring significant debt. One way to challenge this idea (e.g. through a Hobbesian approach) is to distinguish 'freedom' from 'ability': someone is free to work as an apprentice and study and pay for nice boots, washing machines, and cars; they're only unable to at the present time. But, then, governments should do everything they can to ensure that every citizen is able to climb out of poverty and gain access to the same opportunities as everyone else. Do they? (Source)

Left-wing views are frequently seen to house more pity—sympathy, empathy, compassion, sorrow—whatever you want to call it. For example, they afford more compassion to the gambling addict who may or may not benefit from publicly available counselling, the person who hasn’t learned to cook affordably and doesn’t eat healthily, and the individual who can’t hold down a job because their IT literacy is poor and their anxiety affects their ability to get up in the morning and make it through a full day of work.

Those on the right, however, make little use of pity and offer hope in its place. They think, generally speaking, that most people are better off when they live freely and independently and figure out ways to overcome personal obstacles by themselves.

Should we be free to decide how much sugar we consume? The Financial Times once asked: 'Is the sugar tax an example of the nanny state going too far?' Typically, those on the left will say: 'No'. A sugar tax disincentivises consumption and generates funding for health services and for spreading awareness. This intervention is necessary because people will consume sugar to the detriment of their health. They can't be trusted, in totality, to promote their own interests. Freedom isn't fundamentally important, anyway. Those on the right, however, will disagree and say that choice is essential: an individual should be free to consume an unhealthy amount of sugar if they want to, irrespective of the impact, since it is their responsibility to bear and work through. Besides, taxing regressively hits the poor. (The term 'nanny state', of British origin, was popularised by the tobacco industry. It refers to an overprotective state which interferes with personal choices too much.) (Diabetes.co.uk)

II. Free will

One concept that frequently hides under one’s political ideology is freedom.

The state can’t do everything for its citizens. Nor should it: we are not husks of beings but beings of individual will—of plans and preferences and intentions and choices and so forth (unless we lack such capacities). But the society we each want is politically described by an ideology and that ideology is underpinned by how much freedom we ascribe to people. And if people are free, they are responsible for bettering their lives.

Can they come off welfare and take responsibility in a job? Can they choose to get up at 6 am to do a job they don’t like, at least for a while, without having a mental breakdown? Can they choose to stop smoking? Can they choose to stop finding harmful people attractive? Can they choose to stop comparing themselves to unrealistic beauty standards? Can they learn to stop hating their bodies? Can they choose to work harder?

If we think they crafted their own downfalls knowingly, giving them our pity is probably misplaced. If we deem that they cannot sever themselves from their adversity, they probably deserve our pity.

'Pity? It's a pity that stayed Bilbo's hand. Many that live deserve death. Some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them, Frodo? Do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. Even the very wise cannot see all ends … The pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many.' — Gandalf the Grey, The Lord of the Rings (New Line Cinema)

A good case to consider is addiction. Someone politically on the left may lend more credence to the idea that a person has a physical dependency on a substance. Someone politically on the right may lend more credence to the idea that they have the mental capacity to break the causal chains that determine their desires for that substance and that their precarious relationship with it is the culmination of an array of bad choices. Of course, these are very simplistic takes and the nature of their addiction depends on a complex mesh of many factors, all of which have been generalised here.

One possibility always lingers: that an addict cannot reliably act above the core of their physically born desires, say, to choose not to take opium. As Socrates said, ‘No one goes willingly toward the bad.’ This is the kind of approach a health professional takes: they explain, at varying levels, that dependency is a phenomenon physically caused by the presence of foreign substances in the brain rather than a set of self-inflicted, purely conscious desires separate from these interactions. Even for non-substance addictions, such as shoplifting and gambling, subjects experience their stimulation physically.

However, this can be argued to be a purist’s take. Indeed, there is emerging evidence many disorders are born of choice as opposed to compulsivity. This is a controversial view, I know, not least because there are countless counterexamples which suggest agency is eaten up by physical activity: Phineas Gage famously underwent a personality change when an iron bar impaled him, destroying parts of his brain; paedophilia in a 40-year-old man was ‘caused’ by a brain tumour; and it would seem absurd to lay responsibility of depression at the doors of people suffering from it and not their neurological imbalances, however caused. And while psychologists have used words like ‘voluntary’ and ‘reflection’ to describe how someone’s free will is present in their decision-making, they generally have to assume that mental phenomena are separable from physical brain processes.

The film The Butterfly Effect (2004) shows us that the lives we find ourselves living are subject to chance. Its narrative should spur a set of thoughts concerning moral luck, given that some people are more susceptible to making 'bad' choices. For example, they may be born with unfavourable attributes (e.g. slow to learn, disposed to certain physical and mental illnesses, etc.): this is called constitutive luck. They may be born into inauspicious environments (e.g. impoverished, broken families which are beset by emotional turbulence): this is called circumstantial luck. In an uncertain world they may also be victims of pure chance (e.g. because of the result of one punch that put them into a juvenile prison): this is called consequential luck. And then there are limits to how much one person can reasonably come to know, saving space for ignorance. How, then, is it fair to punish people with our political ideologies for unfavourable conditions they are never truly in control of? Shouldn't we pity them for having to exist in them? After all, life could have been very different for any of us. (New Line Cinema)

But if we overstate the role of nature in our lives, we erode personal responsibility to the point of amoral grounds. Some academics, such as Randy Thornhill and Craig Palmer, for example, in offering evolutionary accounts of why men rape, attempt to explain repugnant human behaviour in terms of science: men have greater reproductive eagerness, they say, and are, therefore, more likely to be sexually coercive, which is sometimes seen in the animal kingdom (e.g. in gorillas). The authors conclude that we should adopt the scientific explanation of evolutionary biology into the debate of human agency to find truth in place of ideology. But in doing so they reduce the moral responsibility we ascribe to heinous rapists, who commit morally indefensible crimes, since men have to be more concerted in their attempts to steer clear of their sexual desires.

So we ought to consider carefully how discernible our free mental capacity is from the physical processes that apparently govern the world outside of human experience. Those who pity a person with a greater mental illness disposition or addiction may be forced, by similar logic, to take away at least some of the moral responsibility away from a rapist.

Clearly, there is an interplay between agent and environment. But, here, the lesson is that we have to pay attention to the degree to which someone feels in control of their actions if we are to understand their suffering. Is it laziness or cowardice or do we need to help them through it? From the outside we usually think we would be able to change our fortunes by transcending internal causes (e.g. by losing weight or by quitting smoking). But we say this as we repetitively refresh our social media feeds, choosing the dopamine hit, like rats, instead of pursuing something more meaningful.

People are born into cycles of suffering and become stuck within them, unresolved of their guilt or their shame. Quite understandably, in such cases it’s easier for them to make sense of who they are in the world now than amend themselves to become someone else. Thus we should be cautious with our judgements.

Despite his relatively affluent upbringing with his happily married parents, Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul; pictured) in Breaking Bad finds reasons to feel sorry for himself. He hasn't amounted to anyone special so he gets high to make personal problems momentarily disappear. He needs to get by financially and earn a reputation so he cooks a potent form of meth. However, he eventually realises the grave consequences of his actions, which are becoming too much for him to cope with in S5E7. With new a desire to start taking moral responsibility for his actions, Jesse attempts to end his role in drug crime and accuses his callous, mastermind manipulator, Walt (Bryan Cranston), of showing no remorse for the harm of which they are the causes. But when Jesse attempts to repent Walt throws Jesse's self-pity back at him, with particular regard to the death of a young boy, which Jesse regrets most. Walt says: 'I'm the one who's a father here. What, do I have to curl up in a ball of years in front of you? Do I have to lock myself away in a room and get high to prove it to you? What happened to that boy is a tragedy, and it tears me up inside! But because it happened, what, am I supposed to lie down and die with him? It's done!' But despite Walt's efforts, despite the excuses Jesse's support group provide for his actions, and despite the moral responsibilities no one else is willing to take care of, one day Jesse will find redemption and, with screaming catharsis, escape this torrid period of his life. (Sony Pictures)

III. Existentialism

There are some key existential themes in the philosophy of pity we have yet to explore: namely, suffering, unfreedom, and meaning.

‘Here I stand, I can do no other,’ said Martin Luther, ‘so help me, God’. Luther was alluding to being responsible for the person he is now. But who will take accountable to those decisions in the past?

To feel pity towards someone we have to believe their suffering is a misfortune. That is to say, as per the last section, pity has more grounding when we believe the sufferer cannot improve their circumstances. For if their freedom or ability to improve their situation is seriously constrained, society has probably failed them somehow.

However, it has been shown that people with lower beliefs in free will are more likely to give into temptation and become addicts. This is interesting because it suggests that people who suffer—in this case, because of addiction—are complicit in their downfalls because they don’t believe they were much free to do otherwise. They even find reasons to justify why they can’t help their situations and create narratives for the way things have turned out. Some philosophers think that this orientation of oneself towards suffering is an impulse: an all-too-human drive to find meaning.

Friedrich Nietzsche thought that we have a need to find suffering meaningful to create purpose in a continuous process of interpretation and reinterpretation. In On the Genealogy of Morality, for instance, Nietzsche claimed that we are inclined to live under creditor-debtor relationships. While there are higher creditors (God, society, etc.), we choose to be the debtors because we only favour the 'foretaste' of higher status. In these relationships we feel existential guilt (e.g. from sins, from using society's goods and services, etc.). But we embrace—even enjoy—the suffering that comes with it (e.g. self-discipline, submission, celibacy, diet and rigorous exercise, tradition, sacrifice … ).This is a psychological instinct: the will to power turned against itself: 'the internalizing of man … what he later calls his soul'. Nietzsche did not approve of this ascetic self-maltreatment, which belongs to 'desperate prisoners' filled with 'longing' and without bodily instinct! He took 'bad conscience to be the deep sickness into which man had to fall under the pressure of the most fundamental of all changes he ever experienced—the change of finding himself enclosed once and for all within the sway of society and peace. Just as water animals must have fared when they were forced either to become land animals or to perish, so fared these half animals who were happily adapted to wilderness, war, roaming about, adventure—all at once all their instincts were devalued and "disconnected".' But while this may be so, Nietzsche admits that a desire to suffer meaningfully—which even the privileged share—is a human drive. Then, maybe, sufferers cannot help their desire to suffer and should be pitied. (Edvard Munch)

The idea that we embrace suffering is a spanner in the works of those who build their ideologies on the shoulders of compassion. For if sufferers are the architects of their own poor-decision loops, perhaps we should feel less inclined to offer help. It is the sufferer who holds negative views about themselves: indulging self-pity, they thereby justify their suffering (e.g. by picking up the bottle or by quitting a job). In the example of the drug addict it wouldn’t just be the presence of the substance itself but a perception of its addictiveness which defines its irresistibility and power. The subject rationally creates reasons to take this substance and not detach themselves from addiction; they will find causes to blame for the bad things they do.

In black comedy Heathers (1989), starring Winona Ryder and Christian Slater (pictured), the local Sherwood community posthumously offer sensationalised reasons for why teens at Westbury High School are dying by what is perceived as suicide. The dead, who were nasty and ill-disposed, are honoured and worshipped in death: there must be a good explanation for why they took their own lives: surely, they harboured depth and pain? But, in neglecting the truth, the community fails to uncover the victims and the tragedy that befell them. (New World Pictures)

But if suffering is a choice, isn’t the reverse true: can’t we choose to fight it by appropriating the adversity that apprehends us? That is, can’t an argument be made for using one’s will to meaning (Frankl) to turn our suffering into something productive? As Baruch de Spinoza wrote in Ethics, ‘Emotion, which is suffering, ceases to be suffering as soon as we form a clear and precise picture of it.’

However, some suffering comes with burdens too big. For example, reconciliation might not be plausible for victims of hideous and unprovoked crimes and tragic accidents, from which anguish is paralysing. Even with much-less-violent adversities, people invent reasons to be unfree and choose not to manoeuvre themselves away from grief (e.g. ‘It’s who I am’, astrology, fate). This self-styled subjectivity gives us meaning in prosperity, too, as we mask our luck with personalised reasons for how things fortuitously turned out.

So freedom from suffering, as a reaction to adversity with mental agility, may not be much of a choice at all. We tend to assume people act freely so we can make sense of their characters in the world (e.g. by showing gratitude when they choose to help us or by putting people in prison for actions they chose to commit). But that doesn’t seem to capture the inflexibility of our innermost thoughts and motivations. We find freedom, as a voidance of meaning, terrifying. We only ‘feel free because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom’ (Slavoj Žižek). Why, then, willingly try to detach oneself from the meaningful strings of one’s own suffering?

by Jonathon Francis Deiley & Adrian James Fitipaldes & Nic Edward Pettersen (Northlane)

The truth is we all suffer

We all suffer in life

We all suffer in time

Beat me down, beat me down

Again and again, again and again

Rain hell on me

In life we all suffer

But I will find my way

Through the darkness

This is the truth

In the back of my mind

It's been hiding away

For me to find

The end

I admit that a great deal of my pity for the sorrow of others is guided by a naïve compassion, which stems from a love of this world and my hope for the beings in it.

There is too much unnecessary suffering and I want to take people’s existential journeys, contextualise them, and understand the suffering they wilfully embrace so that I can identify their triggers and help (if they want it). Without any support the fate of many is determined. Those who are imbalanced inside may need assistance to restore their meaningful sense of responsibility. Though they are mostly passengers—undesignated subjects—in this world, they must relate to events in it to want to change it together.

But pity inevitably reaches its bounds in personal responsibility. Sufferers must apprehend the weight that burdens them at some level. Without an excess of pity they must reconfigure themselves, alone, with a newfound purpose: grounded, connected, and with the illusion of control. True recovery cannot come without this step!

Our solutions are that different.

Where one scars another grows; where one is insular another is involved; where one processes another moves on. It’s not simply a matter of telling those who self-pity to ‘grow up’ (Stephen Fry). Philosophy and politics must come together if we are to advance people’s lives. So we must tie in the uniqueness of human experience—of individualised perspective and internal suffering—to one-fits-all ideology.

Weary souls trying to forget

That we're all puppets with a lifetime debt