Do You Want to Be Free?

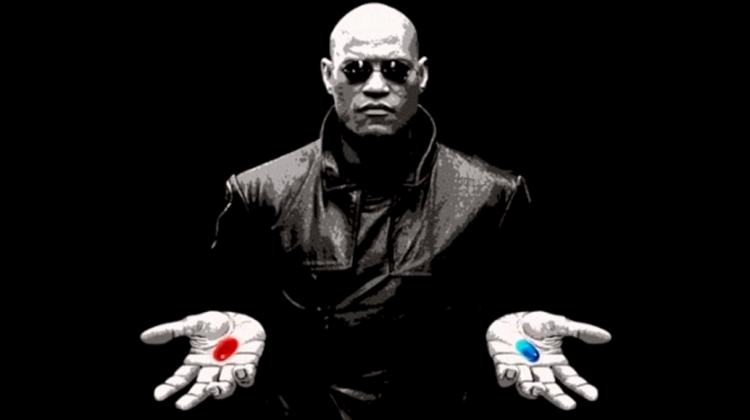

Featured image: In The Matrix (1999) Neo must choose: be free in a bleak world or be enslaved by the ignorance of his own mind. Neo decides the former. Faced with the same choice, would you follow him? (Source)

The question ‘Do you want to be free?’, on its surface, is barbaric. Who would ask for the wilful demise of their own freedom? And, yet, the question requires extensive examination. Freedom is terrifying. You have to fight for it—and suffer.

To be free you must take what’s ‘real’ and be prepared to commit it to the flames. You must incessantly question everything. You must interrogate your reasons for believing X and not Y. You must dampen your hearty conviction and hollow-out your dearly held views. You must be willing to feel the weight of ultimate responsibility when the answers guide you to nowhere.

Do you want it now?

You are free to escape the prison for your mind whenever you are ready. Then again, if you’re being kept comfortable in your everyday reality, why would you?

In The Matrix (1999) we are told of two realities: a cold, lifeless world ruled by machines (pictured) and a simulation, wherein humans bathe in their dreams' falsities as these very machines harvest energy from their bodies. For these synthetically created humans with no histories—humans who convincingly interact with one another in a simulation—truth is a bold choice. (Warner Bros.)

What is freedom?

Freedom is presented to us as something which is coherent and desirable; it’s everything we’ve been sold and believed.

Privately, it’s opportunity, creativity, and control: means to meet our own ends. Politically, it’s the protection of autonomy, the treasuring of rights we deem important, and the furthering of liberty. Naturally, we tend to favour some notion of it; and, for the most part, we flourish.

William Wallace (Mel Gibson) rallies Scottish troops during the First War of Scottish Independence with a famous rousing speech in Braveheart (1995): 'I am William Wallace, and I see a whole army of my countrymen, here, in defiance of Tyranny. You've come to fight as free men, and free men you are. What will you do without freedom? Will you fight? … Aye. Fight, and you may die. Run, and you'll live … at least a while. And dying in your beds, many years from now, would you be willing to trade all the days, from this day to that, for one chance—just one chance—to come back here and tell our enemies that they may take our lives but they'll never take our freedom!'

What precisely freedom should be, socially and politically, however, we don’t agree on. Our of notions are fuzzy and incoherent and based on individually ideology, obscuring a deeper problem: that, fundamentally, we favour unfreedom.

Of course, we don’t favour restrictions (the removal of liberty) when we become aware of them. By governments we are impeded and by law-enforcers we are restrained; and when they do so unjustly we duly fight for change.

We dream of ways to break these iron bars

We dream of black nights without moon or stars

We dream of tunnels and of sleeping guards

We dream of blackouts in the prison yard

Heartbroken, we found (a gleam of hope)

Hearken to the sound, (a whistle blows)

Heaven sent reply, (however small)

Evidence of life (beyond these walls)

Born and bred (in this machine)

Wardens dread (to see us dream)

We hold tight (to legends of)

Real life, (the way it was before)

We dream of jailers throwing down their arms

We dream of open gates and no alarms

Look to the day the Earth will shake

These weathered walls will fall away

However, we don’t always choose the freedom of self-governance (autonomy) when the option is there. We let go of our agency as we are socially manipulated and conditioned by people and our environments and let them define our choices, undermining our autonomy in a myriad of uncountable ways.

As this unfreedom permeates our routines we remain docile, unfazed by our boundaries being infiltrated.

'Style and comfort for the discriminating crotch!' Fry's dreams are invaded by 'Lightspeed briefs' in Futurama S1E6. In this painfully accurate prediction from 1999 we witness the effects of targeted advertisement (in the above case, to sell swish underwear). Today, while our dreams remain safe from invasion (for now), our external environments have been jeopardised: social media feeds are curated for out tastes; major entertainment platforms, such as Netflix and Spotify, deploy algorithms to bombard us with selected content; and governments buy votes with gargantuan levels of directed public spending. Is this freedom: handing over of our decision-making to huge, profiteering companies and powerful governments? If it isn't, not many people seem to mind. (20th Century Fox Television)

It’s true that most of us do not lose our agency by being enslaved—literally or by political means, say, in a theocracy led by a vicious despot or in North Korea. And, generally, we possess some power to autonomously determine how our lives should go, particularly when we reach legally defined adulthood. We like to think this is all especially true in ‘the West’.

Yet, even in countries wherein personal freedom is actively celebrated, people’s lives are filled with external forces which reveal our corruptibility. Take inequality, poor social mobility, pushy families, peer pressure, nepotism, discrimination, and custom and tradition: they nurture us—existing freely within their barriers is a bare and superficial kind of autonomy as we so easily internalise the norms of our environments.

Pictured: Me with my local team's replica shirt on. We firmly believe we form special bonds with objects of our values—political opinions, commitments to sports team, musical tastes—independently. We align with them, we feel them, we want them. But, really, nothing is unique to us. We were seduced by everything which came before us; we were exposed during mere moments in time.

Fear of life

Freedom is a real possibility however we define it. But that’s not the point. The point concerns our lack of want for freedom. The power to choose seems to scare us; we embrace unfreedoms because we know how to.

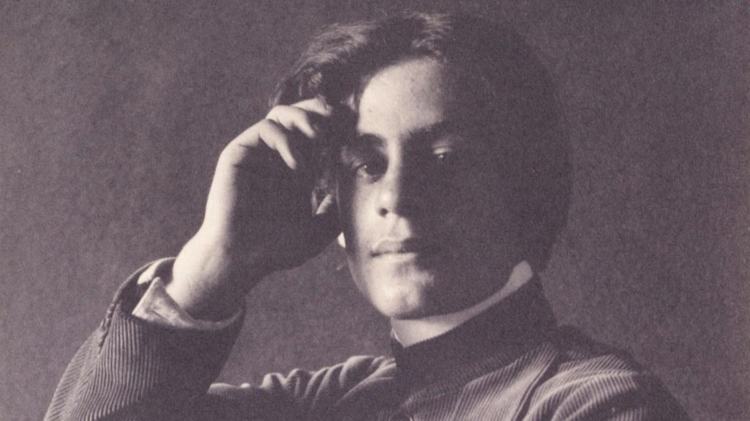

Existentialists, such as Søren Kierkegaard (pictured in the drawing above) and Jean-Paul Sartre, have claimed that we find nothing more terrifying than to be truly free: that we fear being the free, unhindered versions of ourselves, often clinging onto our current values and avoiding our questioning of things. For freedom is a terrible burden; many choose to hide behind a religion or another belief system in 'bad faith' without the responsibility of being free. Albert Camus, particularly in The Myth of Sisyphus, even nudged us towards loving unfreedom. Here's the crux: we seem to fear the lack of meaning life entails when we are free. (Wikimedia Commons)

Of those people whom you know, consider how many choose to act independently with respect to norms. For most the hands of custom and tradition offer identity; and they are gratified. Their experiences are few; but they are taken comfort in. Their liberal societies sanction their ways of living; and they are afraid to disobey them.

We could do jobs which suit our inner passions. We could wear clothes which suit our personalities. We could abandon the belief systems which we were fed. We could stray from the paths which our friends and families built. We could reject the standards systems set for us. We rationally know the alternatives might be better.

Seldom do we pursue these alternatives, though. It’s easier to conform: to marry and have children, to share interests with the friends who’ve appeared in our lives, and to please our small societies with the reputations we’ve contrived within them.

The non-Individual is fortified in the herd: offered immunity from doubting their existence.

The Individual steps out into uncertainty and is engulfed by it, burdened with the responsibility to create identity.

Fear is the consequence of going alone: a wavering hand outstretched into the night.

Human nature

A great many people, in stages, do favour freedom as a choice; only they seem to lose it. Even as they acknowledge problems in their lives and devise possible ways out of them and construct bucket lists they buckle when it’s time to act. Why?

Many philosophers believe that we start out as free beings in our thinking; that, at a decision-making level, we are only constrained by the environments we enter. As we grow we develop preferences that reflect the restricted options which are presented to us: we internalise norms and face manipulation accordingly.

Thus I might actually want to eat risotto one night but, because the chef chooses not to put it on the menu and includes spaghetti Bolognese and Caesar salad, I ‘become’ a ‘spaghetti Bolognese’ guy on the false premise of my own autonomy. I may firmly believe that I am this guy on that night but it won’t really be my freely made decision—I actually wanted risotto—and so on and so forth.

A more-compelling picture, I think, however, is a phenomenological account of freedom whose thesis is that we, as human agents, tend to turn away from freedom as our default way of being despite having access to it.

According to this ontological approach, which is underpinned by the study of reality through first-person consciousness, we are fundamentally free at a metaphysical level; however, on a psychological level, we are only free insofar as we first enact some notion of self-governance effectively—that is, we act with the inner authenticity required of functioning, free beings who act to establish their autonomy.

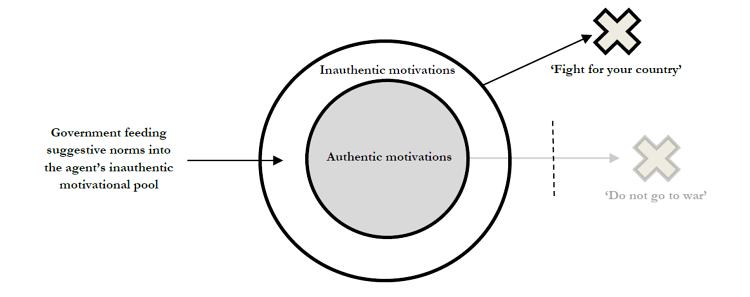

Preference-manipulation of someone's motivations is depicted. Their true or real self (or their 'agent proper') theoretically has an authentic motivation not to go to war. But this motivation is relegated by the internalised motivation to fight for their country, which is achieved through governmental influence over their decision-making and not by authentic endorsement. The dashed line shows how the removal of the agent's freedom could be an external obstacle as well.

The trouble is that we seem to accept unfreedom under very normal conditions: men submit themselves to cultures which are toxically masculine and stifle how they want to be seen and heard; right-wing women are complicit in their own losses in rights; liberal-minded women participate in cultures of oppressive socialisation which make them feel insecure; citizens subordinate themselves to monarchies and vote for their own loss of rights across unions; and followers of religions hide behind commandments and wilfully cower from their gods.

Individuals will contest that their participation in masculine, feminine, left-wing, right-wing, religious, and unreligious cultures are in no way the results of oppression or manipulation, for their decisions were intentional and informed. Then what can we call freedom and what can we call unfreedom?

Freedom is indecipherable from unfreedom: we can’t see authentic from inauthentic. Rebellion is just participation on a smaller scale, whereby every motivation has a genealogy.

In this respect the pious theologian has something in common with the adamant atheist: both steadfastly believe in their own morality. But any morality, like any firmly held belief, is deeply entrenched and existentially laden in the customs and traditions that have taken hold in a particular human society and that people have organised their lives around.

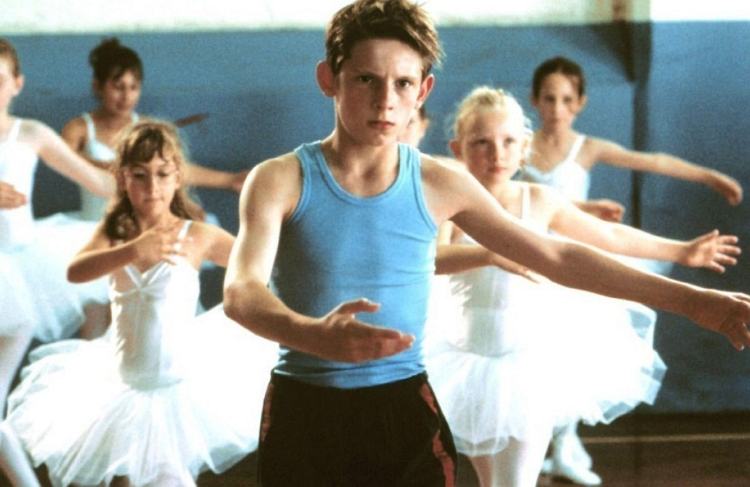

In Billy Elliot (2000) a working-class boy from a mining town in the north of England wants to be a ballet dancer, disobeying the archetypal male stereotype of his community. The film is a celebration of a boy's freedom to pursue a dream which is authentically his. But might his 'authentic' motivation just be a result of events that came before him? Viz, he didn't choose it—not by any wishful ideal of self-governance. There is no 'real self'. (Universal Pictures)

Want freedom? Go get it

The opportunity to be free has to be fought for and is covetable on certain terms, many philosophers maintain.

But why should we want freedom and its responsibility to begin with? It takes guts to create identity which is unique. Plus we often don’t have enough information to make intentional decisions which are immune from external corruption.

More stirringly, there is nothing outside ourselves that can answer the Existential Question of why we should do anything: who are we and how should we live? These questions are characterised by ambiguity and constantly pursue us. We, therefore, fix on things that are clear-cut and make sense within the upbringings and cultures we were born and formed in.

Experience hands us series of choices, which are brought forth and perhaps determined by the exterior world. We’re not free. Are we? We’re destined to be complicit in some interfering game—with ‘autonomy’ no more than what Immanuel Kant called an ‘idea of freedom’ and intention consciously straddling an awareness of antecedent events and what happens next.

Kahlil Gibran (pictured) advocated a philosophically-laid-back notion of freedom, with which we strive for acceptance and inner peace first: pursuits for freedom, itself, are futile and shackle us to unfreedom. 'I have seen you prostrate yourself and worship your own freedom … Ay … I have seen the freest amongst you wear their freedom as a yoke and a handcuff … [Y]ou can only be free when even the desire of seeking freedom becomes a harness to you, and when you cease to speak of freedom as a goal and a fulfilment … In truth that which you call freedom is the strongest of these chains … And if it is a despot you would dethrone, see first that his throne erected in you in destroyed.' — Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet

For existential philosophers such as Simone de Beauvoir freedom comes to an individual, as a state of being, in virtue of trying to attain it. They will find meaning and transcendentally affirm their existence. But, first, they must partially relinquish what made them by embracing the uncertainty of their motives; reasons are ‘made manifest’ in the future. That is:

False certainty about our choices undermines our autonomy in making them: our choices become tyrannies as we belie our chances of real freedom, embracing existence too concretely. Our beliefs should be held more ambiguously than that. We should keep a distance from our beliefs and be driven by an open future.

Consider a man who wraps the value of his existence in external goals: money, power, position, conquest—it is only by achieving these external objects that he feels his existence will be validated. He cannot ever admit to the subjectivity of his goals, even though he himself identified them: to do so would be to acknowledge the subjectivity of his own existence. Alas, he undermines a true understanding of himself: he loses his chance at being free as he is constantly upset by an ‘uncontrollable course of events’ which he will never be the master of. Simply put, he is controlled by his goals—and we don’t want that.

'[T]he whole universe is perceived only as an ensemble of means or obstacles through which it is a matter of attaining the thing in which one has engaged his being. [But despite] all precautions, he will never be the master of this exterior world to which he has consented to submit … To be free is not to have the power to do anything you like; it is to be able to surpass the given towards an open future; the existence of others as a freedom defines my situation and is even the condition of my own freedom.' — Simone de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity. To this end, we must constantly question our situations. A free person places hope in a unique situation but they must scrutinise conflicts along the way, accept the subjectivity of their goals, and only embrace their motivations authentically at a distance: their journey trying to be free is their freedom. (Roger Viollet/Topfoto)

We should want meaning, which comes from within. But it takes modesty, for the required freedom arises from recognising that there will always be a distance between us and these things and aspiring to them anyway. The firmness of our beliefs exposes our soft underbellies: that we are impressionable to systems which are designed to provide ready-made solutions to the meaning of life. But in our unfamiliarity we lay a foundation for life affirmation to become someone who finds meaning and is free.

Now we're alone

Freedom—if there is such a thing—means many different things to many different people, Our wills for freedom tend to be superficially born; most of us only deceive ourselves with surface-level notions of it. This obscures the nature of a fundamental relationship: that our idea of freedom is existentially terrifying.

If I am free to become someone—to revolt against meaningless and affirm my life’s values freely—who do I become and why? Am I more than loyalties to the desires that birthed within me?

Pictured: A still image from the opening sequence of British television series The Prisoner. TWO: 'You are Number 6.' SIX: 'I am not a number; I am a free man!'

If we follow line of Simone de Beauvoir’s philosophy, we might be tempted to believe that, in our freedom, we will discover the depths of our true selves—affirm our life’s values, honestly and critically. However, while self-scrutiny and uncertainty will alleviate from us the directives of some oppressive forces, we are still shrouded by the grandest of doubts.

Wanting freedom requires much-bigger motivations than most of us know. To quote André Gide’s perturbing thought: ‘To know how to free oneself is nothing; the arduous thing is to know what to do with one’s freedom.’ Was he wrong?

Thus we return to the Existential Question: why seek free individualism over the harmonious chorus of collectivism?

To attain freedom is to shed confidence, be daunted by a sense of doubt, and be forced to cut our gaze from comfort.

Indeed, we shy from freedom and embrace unfreedom by placing faith in that which we do not choose. Our faith shows that, deep down, despite our calls, most of us do not truly want to be free.

And, yet, we affirm life, not negate it, by being complicit in the processes that make us, by finding salvation in prison. And in this weakness—this suppleness—we find strength: solidarity, hope, and reasons for doing anything at all.

I. Negation of life

For you will always fear what's out there

Fear the world until you're gone

You will come to realize you were never truly alive

If you deny your existence

Life will pull you back in

The faster you fall the deeper you sink

The quicker you'll leave this all behind

Your cross to bear is a burden you won't realize

So see this as a blessing in disguise

Let the blackened smoke fill your lungs

Breath it in

One day this will bury me as I buried you

Fear the world

Fear this world

II. Affirmation of life