You, Me ... We're All Selfish. So What?

Featured image: Are good deeds self-interested acts we perform to make ourselves feel better?

Born, live—reproduce?—die: every action, all behaviour, is underpinned by this primordial paradigm. Behind each thought, no matter the façade, your fundamental genetic endeavour is to achieve the amoral self-preservation of your genes. To this end you’re hardwired to be self-serving.

It’s inherent: your genes—short, repeated sections of DNA that genetically code everything about you—strive solely to survive. Even when you act with reason and kindness there is philosophical reason to suggest you’re only thinking about yourself.

Yet this perspective doesn’t have to bleak! If you allow yourself to understand these self-interested predispositions, you might be better able to direct your rational motivations for ‘good’. The question is: how?

Selfish genes

To label ourselves selfish isn’t to say we only consider ourselves—evidently, we care for others—however, our intentions naturally favour those who are biologically closer to us. We place greater precedence on the survival of other humans, whilst our families, who share particularly high concentrations of our genes, are afforded special deliberation.

As an example of genes’ influence in our lives, the decision to create a life—life which contains genetically half of you—is fundamentally driven by a disposition to propagate our genes. The joy romantic relationships and new life bring usually come after a primal motivation has propelled into sexual attraction in the first place. A gene-centred view of evolution also explains why behave with paternal and maternal instincts (i.e. to enhance genes’ survival chances).

The selfish gene manifests to the fore of our thoughts every day, though: it’s written into our cognitive reward systems, our fears, and our desires. Such evolutionary programming has been active not just the human race but all life from whom we can trace the same genealogical origins. Its persistence is the lifeblood of survival. As human animals we cannot be so self-righteous as to dismiss the influence of this instinctual selfishness.

Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in On the Origin of Species describes the ascent of homo sapiens.

Nonetheless, if our motivations are only ever self-serving, how can we explain our desire to help others without the expectation of reciprocation, a notion we define as ‘altruism’? Well, it was such cooperative behaviour that enabled our distant ancestors to survive under harsher conditions—to purvey their DNA. Hardly selfless. Then is there such a thing as altruism?

Altruism in nature is underpinned by the gene’s own selfish drive to proliferate, not unconditional kindness. Interestingly, we tend to sever individualistic connotations when we discuss humans and altruism because, as conscious, self-aware, and rational beings, we see ourselves as somehow kind and compassionate. But these features of our existences are still the end products of an evolutionary line; they were still driven by genetic forces.

Anticipating a personal gain, a coral trout points toward food before an octopus flushes it out (as filmed by the Blue Planet II team). Other wonderful examples of cooperation in nature include: herder ants shepherding aphids in return for a nutritious, sugary substance; primates mutually benefiting from social grooming; and cleaner-fish mutualism.

Human … kind?

At this point you might fairly argue that this is pure evolutionary talk which only deals with the primal behaviours of an elapsed epoch, where beings emerged from an aimless primordial soup; that life now is less violent and more thoughtful. Why? Because we’re capable of thinking beyond biological impulse: where other animals are compelled into action by their desires (unless they are trained by us), we’re able to refrain from acting upon ours. In fact, we can distinguish ourselves in a number of ways: we construct ethical frameworks, we fight for justice with them, we appreciate beauty, we contemplate the past and the future, we comprehend consequence and its multitudes of possibilities, we ponder reality, and we despair at mortality.

Even so, Sigmund Freud, in his Project for a Scientific Psychology, asserted that our motive is always to satisfy the individual’s biological and psychological needs. He argued that we operate according to the ‘pleasure principle’, whereby it’s our instinctual animalistic drive to seek pleasure alone. However, it’s clear that we can derive more-reliable satisfaction from deeper and more-fulfilling sources, including love and beauty, than from simple pleasures, such as food and sex. Furthermore, his perspective cannot explain why we intentionally expose ourselves to media that are known to elicit negative emotions, such as tragedy, horror, fear, and disgust.

Clearly, we’re rather complex organisms—persons who exercise reflective thinking. Our cognition is so advanced that, through the sophisticated power of reason, we always possess the potential to do ‘good’; yet this isn’t always implemented. Instead, to somewhat vindicate Freud, we often hunt for superficial personal gratification.

The pertinent question here, then, is: why do we suppose that we’re intrinsically moral creatures?

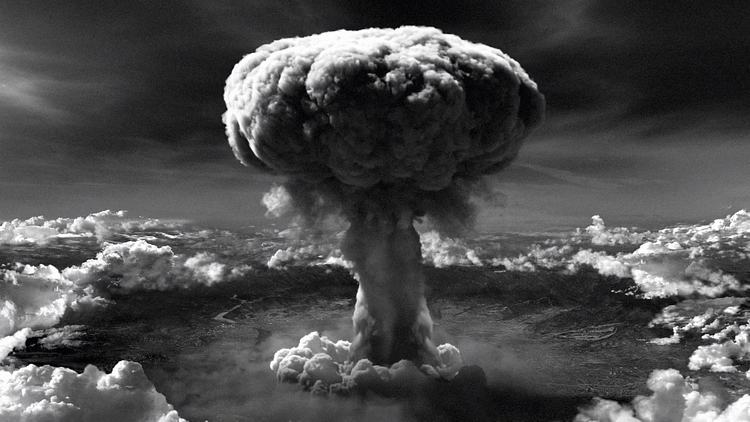

Although we frame ourselves to be morally superior beings, humankind, unwatched, cannot be relied upon to protect and augment its own wellbeing. We will reason to deliver acts of harm for our own gain: we exploit non-human animals for our own short-term satisfaction in the form of food, clothing, experimentation, and entertainment; we opportunistically utilise faceless members of our own species for materialistic personal gain; we will even deliver destruction for the sake of our own ideologies. We are gluttonous and we will destroy Earth.

'Little Boy': The bombing of Hiroshima, 6th August 1945.

But, equally, we’re capable of bringing happiness to others—with jobs that provide value in security and joy to others, with charity, with random acts of kindness. Yet, even when we act in ways that are considered to be morally virtuous, there’s reason to suggest that an ulterior motivation is at the helm of our thinking: namely, the pursuit of our own wellbeing.

We're not selfless

The argument goes as follows.

We only act morally to build our own self-esteem.

We behave with agency. We believe, at least, that we’re responsible for influencing our lives with our choices. So we develop our own ethical frameworks; and when we enact them we believe that we are acting morally. This is validating since we’re operating under the guidance of our own moral codes. The result is a sense of fulfilment.

Self-esteem is an inherent human impulse that has always played an important role in our decision-making. We may recognise its manifestation as a ‘good feeling’ when we behave cooperatively. In a world that we’ve constructed for ourselves, self-esteem is our incentive to behave in what we deem to be morally correct ways.

It’s our moral purpose to pursue happiness; Ayn Rand called this ‘Objectivism’. Our moral choices reflect an attempt to increase personal satisfaction through ‘rational self-interest’. In her collection of essays titled The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism she posited:

Robbing is usually considered immoral—but replace the ‘evil of a robber’ with ‘the compassion of a nurse’ in the example and the argument remains unchanged.

‘Selfishness’ can be understood as concern with one’s own interests, regardless of what we consider to be virtues. It’s our prerogative to think and act successfully in order to be happy; it’s morality’s task to identify the kinds of action that reap self-serving benefit that will serve this meaningful happiness.

Although I disagree with her push for humankind to be more self-centred and recognise that she was a strong advocate of laissez-faire capitalism, I see some sense in her philosophical position. Neuroscientist and philosopher Sam Harris, in stark opposition to Rand, labelled fans drawn to her ideas as ‘malignantly selfish’. In what was ostensibly a counter argument, he said:

While Harris might not see value in her view—I acknowledge its limitations too—I can marry their two philosophies to form a moral conglomerate of self-servitude and decency.

Ayn Rand. For the most part I disagree with her. But her take on selfishness seems helpful in understanding the motivations of our species better.

The arguments may become less arbitrary and more easily understood if we flesh them out with some examples of supposed selflessness.

Why do we keep pets? Is it because we like helping animals or, since their company is linked with our better mental health, do they provide us with something? However well looked after some animals are, we compartmentalise our thinking to ignore the wellbeing of other animals of similar intelligence to enhance our own utility.

We're able to mould whatever moral worldview we deem fit to suit ourselves.

I can hardly talk. Given the impact of climate change and an ever-growing population and that all life on the planet is at risk of eradication, I’d modify many of my behaviours. If I was completely dedicated to my convictions, I’d stop eating as much as I do. I’d never catch a plane for environmental reasons. I’d ensure that my actions were never detrimental unless I was sure that they could ultimately bring positive changes over my lifetime. Moreover, if I was totally committed, I’d go beyond sustainability to sacrifice my own life to render my impact on Earth to zero. But I possess a will to live. I’m selfish and I want to survive; it’s how I’ve been assembled.

What about my political convictions? What do I truly believe in? I dedicate myself to my own causes. It would be objective and fair to allocate most resources to campaigning against the issues that adversely affect the most people in the most significant ways. Yet I don’t; I have my own motivations. In this regard, why don’t I vocalise my opposition to more human rights violations abroad instead of, say, criticising the UK’s monarchy so much? But I’m not alone here.

We're selective about which charities we volunteer for and donate to. We might've been personally affected by the loss of a loved one and relate to the cause through empathy. Perhaps we tangibly fear the negative impact of an issue if we don't assist in the fight against it.

We value topics that relate to us the most. I care about other animals, maybe because they were always around me as I grew up. I care about inequality because I believe I faced some social adversity growing up.

We want to instil our visions and implement our ideas to make ourselves happy. Why am I writing this article? Why do I write any article? I want to impart an impression of my particular vision—perhaps to illuminate, to enlighten, to persuade, or to learn something for myself. I want to see the growth of my own ideas—a reflection of myself—the fruits of my ego—in the world that I see fit for us because it confers meaning to me.

The emphasis of our own values can, if we're not careful, skyrocket into deluded and impotent narcissism—egos swollen by the sheer amount of faith we place in our own worldviews. Heeding this, we should make an effort to think and treat others' views with humility if we care to make a positive difference.

The road to righteousness

Darwin and Freud offered inward-looking insights: the theory of evolution beautifully describes the selfish gene’s dominion over humankind; the pleasure principle elucidates the physical draws of sex and explains the chase for superficial, materialistic pleasures. However, the story is incomplete. The vast potential of human reasoning is there to be harnessed for the sake of decency. We’re selfish, yes, but we can still behave morally.

First, we must accept that we’re irrational creatures who can’t control or suppress selfish animal instinct, only refrain from acting on it. This much is necessary for our mental health. Instead, we should seek to understand our irrationalities and be culpable to them for ‘good’.

The greed of Black Friday: A scarcity of resources often brings out the worst in people, indulging our ugly instincts. Game theory, too, aptly demonstrates human selfishness.

I’ve argued that we’re innately selfish. But this doesn’t mean that we can’t build ethical frameworks which reap ‘good’. Defining universally accepted, objective moral behaviour isn’t possible, for there’ll always be something to disagree on: our moral standards are conditioned by society’s nurturing hand, where what’s moral to one group might seem immoral to another. Moreover, reasoning powers only help us with the task at hand so much. We can rationalise all kinds of individualised advantages. Meanwhile, even when we have full faculty of mind, we can be the unwitting subjects of undetectable manipulation, which guides our thinking.

Nevertheless, there are prevalent moral standards. They dictate that values of kindness and compassion—sharing, giving, listening, understanding, considering—are virtuous. This is a strong foundation since, regardless of what ethical framework we follow to arrive there, we are centring our morality on others. If we reasonably assign importance to these values, we will help others whilst selfishly promoting our own self-esteem according to our values.

A Buddhist monk is acting ethically according to his belief system. He thus lives by his moral standards and is fulfilled in return. Irrespective of creed or school of thought, I think the central tenet of an ethical framework, religious or secular, must stipulate that helping others is unconditional.

It’d be fair to ask why you’d ever lend yourself things that didn’t make you happy directly. But, propelled by reason, concern for others needn’t be a hindrance: compassion is conducive to the growth of our mental and physical wellbeing. Embrace it.

Don’t question it: pander to your innermost selfish self to, effectively, be moral, for selfishness and morality don’t have to be discordant. Commandeer your human instinct to harmonise your conscience to the wellbeing of others. This will evoke fulfilment, lasting satisfaction, and comfort with one’s self. Without a moral compass you’ll be left shipwrecked—numbed by superficial pleasures and insulated by the absence of connection. With one you’ll have meaning—purpose—outside yourself.

#DoSomethingForNothing: Joshua Coombes raises the spirits of the homeless by providing them with free haircuts, bringing dignity back into their lives. This is not nothing.

Embrace your selfishness

‘Selflessness’ is disingenuous since human beings can be exposed as inherent self-servers. We assign value to the wellbeing of others on the condition that we can derive personal satisfaction from them. Everything we do is self-serving; each thought, rational or irrational, can be deconstructed to reveal this. But if the world becomes a better place as a result of our raised self-esteem, there can be no shame.

Self-servitude doesn’t invalidate positive impact: ‘selfish’ morality is indistinguishable from ‘selfless’ morality. In the act of self-serving compassion you’re not masquerading as a good person: you are one. Self-esteem is just a welcome by-product—no, an incentive. So correlate your happiness with others’. Rejoice at acts of kindness to feel buoyant. Welcome the desire to be perceived as a good person. Back this up. You will find meaning.

Only humans can seek justice for everyone and everything around us. Selfishness must be permitted such that we can harness the truest of motivations for moral behaviour. Employ it. As Richard Dawkins put forward in The Selfish Gene:

'Let us try to teach generosity and altruism, because we are born selfish. Let us understand what our own selfish genes are up to, because we may then at least have the chance to upset their designs, something that no other species has ever aspired to do.'