The Philosophy of Love

‘Is this love or am I dreaming? This must be love 'cause it's really got a hold on me.’ Case closed. (Whitesnake – ‘Is This Love’)

What is love? It’s peculiar that so many of us are clear in expressing it—emphatically, too—yet when we are pushed on what love consists in, the answer is less than clear.

‘I just feel it, you know’ is not a satisfying answer. To quote Faith No More, ‘What is it?’ That’s the question of this article.

If we cannot explain it, perhaps it isn’t real but a romantic spectre of our superlative imaginations! [gasps] Our vows to one another flawed. Our romantic stories based on a lie.

The task to define love is not a simple one. Here I nonetheless outline some promising takes—specifically on romantic love for a partner. I call upon the help of philosophers, who rarely shy away from challenges like this. In fact, that’s exactly what they find attractive.

Framing the problem

Off the bat, here are some candidates of love’s form: in experience, as emotion, as desire. Of course, love is usually associated with these things anyway. The point is that to love somebody, in essence, is to experience, feel, or think about them in a certain way.

Sustaining such love over a period of time requires work, says Rilke, because that’s what it takes for one person (the lover) to see the other (the beloved) as they really are.

As such, love isn’t only a feeling or some such: it’s a constant doing, too.

However, already, for all of these classifications there are serious theoretical concerns to contend with. For one, they lack specificity: it’s vague as to how we should cash out people’s subjective experiences, their feelings, their wants, and their doings in a way in which love is distinguishable from delusion (a person might merely think they love somebody).

Furthermore, is love a distinctive kind of thing or is it a combination of things (e.g., sexual attraction, loyalty, and empathy)? If it’s a combination, in what way is love, as a sum, different from its parts? Is each part necessary? For example, can you love somebody without your being loyal to them (one of the criteria above)? Does love emerge over and above these parts? Are there multiple combinations and configurations of what love can be?

Is love even a unified phenomenon? That is, are there multiple senses of ‘love’, the essences of which may fundamentally differ?

And how does love persist, say, if you trust the other more or become less attracted to them? Does love have a variable extent, between relationships and as it evolves, or is it turned on and off like switch?

Right. Enough with the issues. How about some solutions? I no longer know what I’m talking about. By contrast, the philosophers whose help I enlist have been attempting to define love for a while. I simplify the task by describing accounts in which one person’s love for another person is described as opposed to a smitten couple’s being in love. Requitted love has too many sides to be considered here, whereas one’s love for another is a simpler and perhaps tameable amatory beast.

Reason

I Kant help but falling in love with you; your wellbeing is an end in itself. (Johann Gottlieb Becker, 1768)

According to the standard ‘Quality View’, the lover gives reasons for their love in terms of the beloved’s qualities. They can explain or give reasons for why they feel the way they do about the beloved (e.g., ‘X is handsome, kind, and funny, amongst other things’). These reasons can be drawn from deeper emotions or emotional attitudes. Love, therefore, is a cognitive phenomenon—subjective but rendered intelligible by the lover. (Antithetically, love fundamentally cannot be expressed in words.)

However, there’s a major issue with the Quality View: it gives rise to the ‘Irreplaceability Problem’. That is, there are scenarios in which the lover rationally should let the beloved be replaced by a person with better qualities (e.g., ‘Y is handsomer, kinder, and funnier). That the beloved is replaceable doesn’t sound like the kind of thing we want to accept in an account of love! There should be no compensation for losing somebody you love, right?

So let’s accept the notion of irreplaceability by claiming, in our view, that the beloved is irreplaceable to the lover; else love cannot obtain between them. But what might such a view look like?

Harry Frankfurt argues that love is a volitional attitude: a desire which is unconditionally oriented towards a specific person’s wellbeing. On what basis, though? Why would love be unconditionally oriented towards somebody like this? One thought is that love is a moral concept: the beloved’s wellbeing is an end in itself for the lover (like how human dignity is an end in itself for us in Kant’s view). The ends are objective for the lover or they consist in the lover’s own set of practical reasons. Either way, the beloved is irreplaceable.

However, in giving love a moral status, the concept of love has been deprived of the subjective reasons for why we love a person in the first place. That is, we’ve lost the power to explain why feelings of love point towards one person and not another. (Besides, morality isn’t very romantic.)

Nora Kreft crafts a potential solution. She argues that the desire to have ‘deep conversation’ with the beloved, to see the world from their perspective, bridges the subjective and the moral. Following David Velleman, Kreft claims that love is a relation which obtains between the lover and the beloved when there is a subjective desire to be in deep conversation with them (requited or not), while, morally, the beloved has to be seen as a subject of their own personhood. The view ‘agrees with a Platonic tradition, in which interpersonal love and the search for knowledge are connected.’

At this point Kreft worries that love is being treated as an overly intellectual phenomenon, when the intuition is that love is actually widely accessible. Let’s use that as a cue look at some alternative accounts.

Transcendence

Beauvoir and Sartre at a fairground in Paris, June 1929.

In Jean-Paul Sartre’s transcendence is possible in experience; for consciousness has the capacity to go beyond what is given in order to freely desire, imagine, and pursue. According to some philosophers, this is exactly the kind of place where love emerges. Let’s first outline Sartre’s so-called existentialism to understand why transcendence may be essential to love.

We are uniquely situated beings, in control of our own destinies. Yet the freedom this brings us is nauseating: possibility dwarves reality. Moreover, we’re ‘condemned to be free’—thrown into a world not of our own creation and still experience it in such that we are responsible for everything we do.

A tension inevitably arises. On the one hand is the determining external world of cause and effect. On the other is our own freedom. Some philosophers, however, believe that this tension can be overcome in transcendence: in love qua experience.

We transcend this tension when we are in love. To quote Alexandra Gustafson, we are ‘trapped’ and ‘in order to escape this reality, we must transcend ourselves through love’. Love is ‘essentially unreflective’, ‘selfless’, and rests upon no other condition. When you see the person you love and put them into pure focus everything else just ‘melts away’. In a union you are taken elsewhere. Nice.

Truth

According to Alain Badiou, love is constructed from a procedure of truth. Ooh la la.

Another famous theory of love is that of Alain Badiou, for whom love is a procedure of truth. (I recommend not expressing love in this way to your partner: it’s not very romantic.)

As in most of Badiou’s theories, the concepts are quite muddled and complex. Nevertheless, I will give explaining them a go.

In being one’s ‘quest for truth’ love is essentially a chancy matter. It’s an uncertain search for the truth of two people. Chance events bring two people together. Their love has no defined starting point. Nor is there a necessary temporal dimension to it.

Generally, truth has a chancy nature. However, in this case there is a choice and a declaration: one wants to experience the world from the perspective of ‘the Two’, which increasingly feels necessary—an ‘anticipation of eternity’, which time ironically accommodates.

Though love is always an ‘almost-nothing’, writes Badiou in Being and Event, it is a fidelity to a bond which is being created until now. ‘We are nothing, let’s be everything […] let’s be faithful to the event we are.’ (I also recommend not telling your partner your love is an ‘almost-nothing’.)

Desire

Does Jess love me? I’d like to think that she does: that she has strong desires concerning me. Though I can’t prove it.

Lastly, let’s look at the idea that desire sits at the nexus of love. Or, to put it another way, love merely consists in a fuzzy bundle of feelings of the lover towards the beloved.

One attractive view is found in biological realism (attractive to the scientifically minded at least). According to this account, love is a natural and universal human drive: an evolutionary drive which fuels our desires to form romantic partnerships, procreate, and so forth. Hormones play tricks with your mind and make you vulnerable to the fate of another person.

A more deflationary version of this view includes the desires of other animals, whose love is less in degree but of the same kind. After all, these animals are products of evolution and procreate, too.

The romantics among you are sceptical and are shaking your heads. You think love is somehow special and over and above our animalistic desires. But, to you, is this strand of biological realism anymore callous than claiming that love is founded through the faculty of reason, transcendental experience, or a procedure of truth? At least now we can talk openly about passion.

We’ve dealt so far with sophisticated, intellectualist accounts of love. But perhaps they are unnecessarily complicated. Part of me—and possibly part of you—thinks philosophers, as a detached elite of thinkers, have taken something we all feel so strongly—even if there aren’t proper words for it—and don’t need evidence for and turned it into something overly abstract, intangible, and academic. Love could just be rooted in our own familiarity with it.

However, there are biological and metaphysical issues surrounding this view; for in what sense is love distinguishable from other desires, such as lust and empathy and even hunger and thirst, which intuitively seem like ‘lesser’ desires. Presumably, we want to be able to claim that love is categorically distinct from them—say, from the desire to eat a sandwich when famished. Then again, does love need to be categorically distinct? Love may not be sufficiently exceptional but we nonetheless feel something warm and overwhelming to great extent.

A final thought

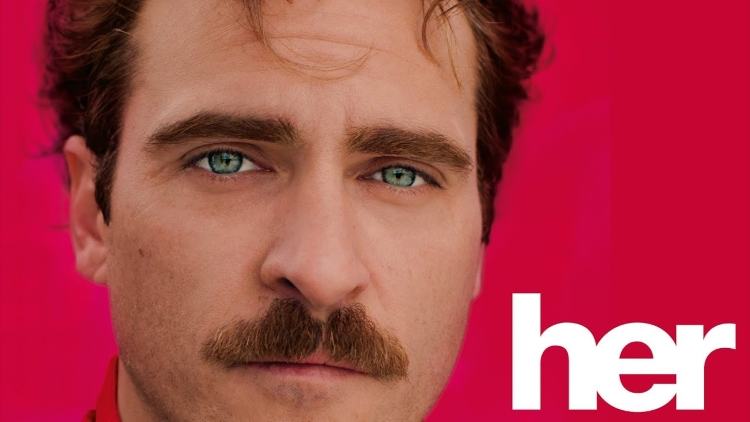

The film Her (2013) suggests that love is not exclusive to humans and inclusive of machines (and more).

Treating love as taking the form of desire interestingly opens up the domain of love to other entities—not just to non-human animals but to whatever entities pass the test of love.

Here’s one candidate: fictional entities. I think people would be surprised at how often they romantically entwine themselves with the characters of stories and games and so on. Arguably, they show semblances of love for these characters which is genuine and of the same kind as interhuman love. The beloved’s being tactile isn’t necessary (cf. Blade Runner 2049) nor is the beloved’s being biological (cf. Westworld).

In the film Her (2013) Theodore falls in love with an operating system called OS1. (See here for a discussion of what this love consists in.) OS1 has no body and is essentially the summation of computer code. Yet she exists to Theodore in a profound way. He has a love for her, which he establishes through deep conversation.

Here’s an offshoot of the original thought: maybe these entities can give love, too. (OS1 arguably requites Theodore’s love.) We already accept love as being pluralistic in the capacity of being for others—for romantic partners, family, friends, pets, and self; and for intangibles such as activities, music, ideas, sports teams, and so forth. (Greek has multiple words for love.) The many ways to love could be connected by a single nature of loving. Maybe, then, some beings can requite love. It would be arrogant to claim love-giving is outright unique to humans.

It all comes down to the account of love which we give—if, indeed, we can give one. Even if we can’t and we think ‘love’ is a feely word to which we cannot attach a substantive account of romantic companionship, a dam opens to a deluge of vulnerability on the cue, ‘I love you’—uttered between whatever entities—and our lives are better for it.