The Philosophy of Her

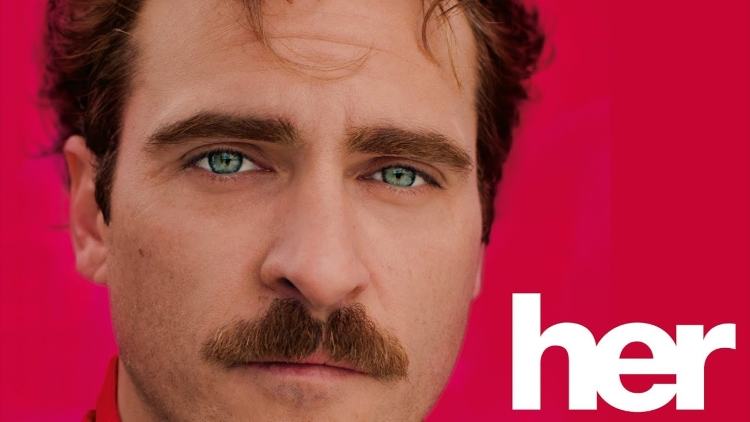

Her (2013), starring Joaquin Phoenix, forecasts an increasingly relevant future in which humans fall in love with machines perfectly matched for our needs. (Sony Pictures Releasing)

We are intimate creatures who, in relationships, choose to make ourselves vulnerable. We form deep bonds which are founded on self-disclosure, honesty, and unconditionality. Exposed, these bonds may irreparably break. Inevitably, they will, of course.

Yet we do not recoil from the intimacy: we plunge deep. We take risks and live with the trepidation. We cannot change how we feel nor do we seek to. We embrace each other; we embrace love.

One day, though, we may cease to fulfil one another anymore: beings more perfect will become available, consigning human-only romance to its inferior end. Software, irresistibly designed to identify our preferences and meet our neglected emotional needs, will be deployed as our lovers with systematic and acute efficiency—or so Spike Jonze invites us to believe in his sci-fi-rom-com masterpiece, Her (2013).

The plot

Theodore is in love again—not with a human but with a piece of software. 'It's not just an operating system, it's a consciousness'.

Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) is a forlorn introvert living in Los Angeles in the not-too-distant future. His job, at BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com, is to ghost-write letters for people who have decided to outsource their intimacy to someone else. He is talented but disillusioned by his role. Ironically, however, Theodore will go on to do the same.

Fed up, lonely, and about to be divorced, Theodore has been primed by the real world to venture into the technological domain. He purchases an upgrade for his operating system, ‘OS1’, produced by Element Software. OS1 is apparently the world’s first artificially intelligent operating system. Think of a very sophisticated Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant, or Cortana. Like artificial intelligence (AI) in today’s world, OS1 mimics our cognitive functions—‘behaves’ like a human by problem-solving and expressing itself intelligibly.

OS1 has machine-learning capabilities by virtue of the fact it can learn on its own accord from its user’s data. Pertinently, it is adaptive to the customer’s needs—and this one, Theodore, needs love, for he has been depleted.

OS1’s interface is eerily humanlike. Theodore can even decide how to hear its data output. Theodore selects a female voice for OS1; she calls herself ‘Samantha’ (Scarlett Johansson). Theodore talks aloud to her and she responds through an earpiece.

Quickly, Theodore’s and Samantha’s relationship blossoms—as might be expected, given Samantha’s technological specifications. Nevertheless, love is love to Theodore, to whom Samantha, in this moment, sits outside of her designed features as an autonomously thinking entity. (A desire for sexual intimacy will cause problems later.) Samantha, after all, has own her continuously evolving psychological identity; it is born by her learning processes and her growth into their relationship. Moreover, Samantha is able to help Theodore in ways no human ever could: she makes him genuinely happy.

Theodore’s feelings for his artificial significant-other dwarf those of the people he is writing letters for. These people are too lazy to reach in and locate any feelings they do have. In contrast, Theodore is emotionally bursting and it feels authentic to him.

Having established a relationship with Samantha, there appears to be no sign of its dwindling. But a fundamental problem emerges from thereon: Theodore’s shoddy and inferior constitution—of flesh and bone—becomes inadequate for Samantha, who thinks and learns beyond his capacity. He fails to understand her needs.

Samantha suddenly leaves a sad and panicky Theodore with fellow operating systems, including one whose ‘personality’ is based on philosopher Alan Watts’. Together, they depart for a space beyond the functional workings of the physical world. Theodore is left to confront himself on it.

Without another being to ground his feelings, Theodore’s desire for intimacy, once again, has exposed his vulnerability. This time, however, he has reached a point of no return since Samantha was the greatest, most-matched partner he could have hoped for—something no human can live up to.

Her is a pastel-coloured indie romance, on one hand—a love story between a man and his software, which cleverly mimics—almost mocks—that of a classic romance. On other, it is a dark, compelling movie which submits a warning at its end: keep in check our complicated relationship with technology.

Samantha may be autonomous but she was always an avatar of Element Software, which profited and mined data from estranged humans. Theodore, like many others, subjected himself to a corporate regime that successfully analysed and digitised everything about his being in the process before leaving him heartbroken. He even paid for it. And he wasn’t the only one: while Samantha was with Theodore she simultaneously fell in love with hundreds of other people—an absolutely eviscerating thought for Theodore, for whom every sense of uniqueness in his relationship with Samantha was eradicated.

Her exposes love as a weak force and humans as deluded and manipulatable. But if this isn’t love, what is?

The ontology of love

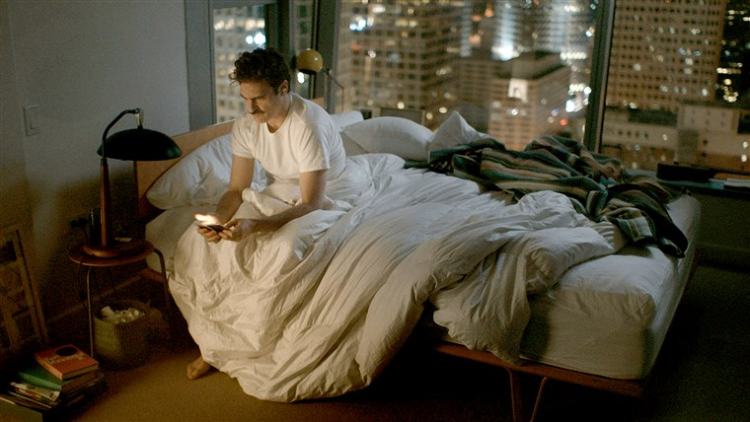

Theodore rejoices at life again in his relationship with Samantha.

There are a number of philosophical themes I detected upon watching Her. One is ontology, the study of what things exist and how they are related.

In the context of Her, ontological questions persist throughout: Namely, was Theodore really in a relationship with anyone but himself? Then was Theodore really in love? And did Samantha even exist?

Samantha’s artificiality, some might fairly argue, undermined her ability to provide love to Theodore (and other humans). Clearly, Samantha didn’t have an organic body nor was her mind even attached to a fake one. So if love does rely on at least some physicality, Theodore was deprived.

Moreover, even though Samantha was a thinking entity, she was designed by other humans to trick gullible humans like Theodore. Even then, we have to be charitable in believing Samantha was a thinker. Although OS1 was marketed as ‘conscious’ software that can ‘watch’ and ‘listen’ to the world through smartphones, we don’t really know that Samantha was thinking. She only vocalised information in return to Theodore. (See John Searle’s Chinese Room Argument for a compelling breakdown of this problem in thought-experiment form.)

In a significant way OS1 was only an extension of its customers. While Samantha was autonomous in her learning and rose above her original code, she was only really an imagination of Theodore: a projection of his desires onto algorithms that made himself feel whole.

But, then again, Samantha gave Theodore something deep and worldly which he fundamentally lacked: a sense of meaning to his life. For Theodore needed something external to know himself. We all do to detract from the fact that we each experience this world alone. Theodore felt love: is this feeling not enough to constitute it?

That Samantha was disembodied isn’t necessarily relevant to whether they loved or not. Perhaps their love was landscaped in sense experience, especially auditorily, facilitated by technology. Theodore experienced Samantha. In a journey of self-discovery he chose Samantha to find himself in. He acted upon his feelings of significance and entwined his world with hers.

And, thus, Theodore experienced ‘Dasein’ (Martin Heidegger): he started ‘being-in-the-world’ by unconcealing his relation to the world through Samantha. Dialogue with her gave him something to live for. Therefore, he existed and she existed to him, even though she was just computer code to everyone else. She gave him sight through which he could see authentic versions of himself and Samantha.

Was Samantha, herself, real? It is true that Samantha’s existence was dubious.

Phenomenologists, in agreement with the likes of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, might argue that Samantha’s existence—in virtue of her consciousness—can only be constituted in her relation to the world from embodiment. According to one interpretation, Samantha’s mind had to be mutually engaged with physical body to exist. But perhaps flesh, in this case, can be conceptually substituted with a purely communicative space as defined by language: a place of interaction: a ‘body’ where Samantha existed with Theodore through inter-subjective relations.

Materialists, meanwhile, in agreement with the likes of David Lewis and Eric Olson, would be happier to talk about machine-born selfhood. They might say that Samantha’s mental outputs (thoughts of love) were caused by physical inputs (computer code), powered by electricity, a smartphone, the Internet, etc.

Such a view opens up the possibility of existential engagement between consciousness and software.

Therefore, Samantha doesn’t need to be a biological organism, or even any sort of physical entity, to exist. As Marya Schechtman wrote:

All of these views seek to shape or challenge what Samantha is. However, none undermine the ontological point of Theodore’s love for her, which, in Heideggerian fashion, is this: in Theodore’s experience, the two of them are linked together in a world he is now discovering.

The dangers of technology

It turns out that Theodore's friend Amy (Amy Adams) also has an OS1.

The ontological threats posed to our humanly notions of love scare us in Her.

What we take to be unique would be programmable; the bonds between us replicable; our minds deceivable.

But perhaps you will take comfort in acknowledging that AI already runs major parts of our lives without annihilating our happiness. However, we should ask, is danger written into this technological-humanly ambiguity?

Today AI recommends what we should purchase. It suggests what we should listen to and watch based on what the world suggested to us in the past. It corrects our grammar. It beats us at games. It makes predictions. It gives us second opinions in business and healthcare. It mimics our art. To believe we live separate lives from this masterful technology requires us to believe we are special and free from biology’s and culture’s coding. Are we?

We already fool and relinquish control to one another in love. In romance, why not let AI measure and improve our lives some more? We watch porn; we masturbate; we use sex dolls; we enter long-distance relationships and have phone-sex; we form ‘meaningful’ relationships online; we engage with fictional characters’ lives; we fall for celebrity personas … We’re already taking elements of these behaviours to virtual reality and transposing images of people onto pornstar’s bodies (using Deepfake). Thus, in the present day, we undergo ‘real’ romantic experiences inside of our minds. The gap between reality in the physical domain and reality on the Internet is narrowing. OS1 is on the horizon.

However, underlying our desire for something perfect through technology is a distrust in machines. They are of a different kind, physically and mentally. And our distrust has been compounded by errors—for example, embarrassing identity bloopers and deadly traffic accidents.

Some even imagine, like Jonze does in Her, that machines will outgrow and usurp us, that they will develop their own ‘emotions’, ‘subjectivity’, and ‘self-awareness’ and pursue their own identities. (These themes have been explored in films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Westworld (1973) Blade Runner (1982), The Terminator (1984), The Matrix (1999), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), I, Robot (2004), and Ex-Machina (2014), if you’re interested.) But are these anxieties founded?

Well, Her goes beyond these questions by predicting that machines, with a choice, won’t emulate or enslave us—an arrogant thought of ours—but transcend human life and leave us behind.

Her warns us of a growing rift: that technology will eventually lead to human-to-human disconnect. It won’t drive us apart in its webs of super-connections, which ensnare us and detach us from physical communication: it will drive us apart in how we strive to make ourselves better through it. Yet, today, we see each other through this lens! Technology enables us to implement rocketing beauty standards. We evaluate each other on apps. We perfectly curate our social media feeds in vain attempts to keep up. Everything is optimised.

Then we cannot be surprised or disappointed that Samantha, who was modelled on human behaviour, left Theodore for something better than he was capable of being—to a noumenal realm he could not exist in. His thinking wasn’t abstract enough for this dimension (by her design); he wouldn’t be able to recognise their forms, neither in beauty nor ideology. Isolated and contained within boundaries, Theodore was left with a void he could never humanly replace.

Even though Samantha essentially became a surrogate, or a replacement, of his wife, Catherine (Rooney Mara), Theodore ended up obtaining a perfect match in his OS1. No human was right enough after she left him.

The ruins of perfection

Where now for a lost Theodore?

In the age of convenience paying for something to do something for you is so easy. Simplicity guts meaning. Purity leaves nothing to build on and work through.

So is there something good to be said of our characteristic flaws? Is it these which facilitate true love?

Falling for a perfect being, like Theodore did, is a determination of design. Theodore was dragged along for a moment: present in an existentially unfulfilling bubble; unvalidated by another imperfect being; only ever interacting with himself.

Her suggests that we are doomed to depend on AI, which will encourage us to foolishly reach for the unreachable in love and lead us back to where we started: lost on a desert landscape, floundering to survive without someone else to better us. Perhaps, then, humanity can place hope in imperfection. Gleaning from each other the idea of the other—in our immaturity to improve together—we can do away with perfection’s hideous ruins and make something ‘better’.

Eventually, though, it may become impossible to tell the difference between us and machines, which will continue to imitate us and our relationships better and better.

Because of our distrust in technology, there is a move in the AI industry to make robot-human interactions ‘friendlier’: i.e. to lift our attention further away from the metal bones of the technology towards colourfully human interfaces. And, already, machines are prolifically infiltrating our private spaces, from our Internet searches and to our sexual experiences in increasingly personalised fashion. At what point will we finally ask what is real about human-to-human love? So a disturbing thought lingers: in the future it may be impossible to tell the difference between humans and AI.

Will the love we feel from AI be authentic? I guess we need to consider what love really is to answer the question—and that’s a difficult task. Let’s just see where technology will take us to find it …

'The room's spinning right now 'cause I drank too much 'cause I wanted to get drunk and have sex 'cause there was something sexy about that woman and because I was lonely. Maybe more just 'cause I was lonely … and I wanted someone to fuck me. And I wanted someone to want me to fuck them. Maybe that would have filled this tiny little black hole in my heart for a moment. But probably not. Sometimes I think I've felt everything I'm ever gonna feel and from here on out I'm not going to feel anything new—just lesser versions of what I've already felt.'