Foucault on the Invention of Man

Inspired by Kant (b. 1724), Michel Foucault pointed to the beginning of the 19th century to identify the origins of 'man', the time at which we began asking why we see the world as we do, not simply asking why the world is the way it is. Bidirectionally, we consider ourselves subjects and objects; we conceive of 'man' in a situation.

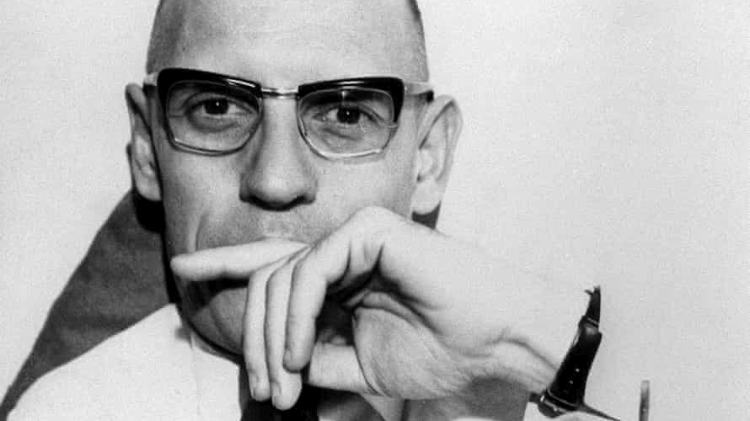

What is ‘man’? According to Michel Foucault (b. 1926; pictured), ‘man’ is an invention, one which is liable to change. ‘Man’ here doesn’t signify a gendered being; rather, it shares meaning with notions like ‘humankind’ and ‘human nature’.

Our knowledge of these ‘truths’, says Foucault, is socially constructed and constituted under conditions of power (‘power’ represents an ‘archaeology’ which continually produces new ‘truths’, not a metaphorical gun to the head). We build our ‘truths’ in workplaces, schools, and prisons, whose overarching infrastructure shapes our ‘docile bodies’ into acceptance.

Thus the supposed truth of ‘man’ is an idea embedded into us. We are vehicles of a ‘truth-event system’, by which ‘man’ is ‘historically determined and situated within our culture‘—at best, temporarily. Our societies follow unconscious rules, born out of everchanging historical conditions, which determine ‘man’.

We only have to trace a genealogy, beginning in the 19th century, to unearth the history of ‘man’ in one instant. For example, ‘man’ apparently has a fundamental set of interests in virtue of biologically evolved traits (Darwinism); ‘man’ possesses self-authenticity belonging to inner subjectivity (Sartre’s existentialism). However, each view is mistaken, writes Foucault. For ‘man’ is an invention whose properties will be erased again in the future—perhaps eventually to the point of no return.

‘God is dead,’ declared Friedrich Nietzsche. ‘Man’ now walks lonelily on thinly constructed meanings. These ‘glittering surfaces’ are crumbling, says Foucault. Already technology is eroding the boundaries of what ‘man’ is supposed to be.

Some fun facts for you:

- Michel Foucault, a Frenchman, was once tutored by Maurice Merleau-Ponty at École Normale Supérieure.

- Foucault argues in his PhD thesis that the distinction between madness and sanity isn't real but a social construct. (We've written about this as well.)

- Foucault worked and lived in Sweden, Poland, and West Germany. Generally, he was a systematiser: a post-structuralist and discursive epistemologist.

- He was also a political activist.

- Then there was his philosophical feud with Sartre …

What a ‘man’!