The Illusion of Causation

Featured image: Scottish philosopher David Hume.

Hume's regularity theory

David Hume’s theory of causation (Hume 2008) has had profound effects on philosophical thinking and is still considered relevant today. But his ideas are counterintuitive: he claimed that our minds play no role in causation; that we do not make decisions which move the Universe from one state to another. We may apply the notion of causation to all kinds of phenomena, from subatomic particle interactions to the mechanics behind the expansion of space, but what we really care about here, in the context of metaphysics, is whether we affect how things turn out in the world.

Hume claimed that, since we are all born with tabula rasa minds (blank slates), we are born with no innate knowledge of causation. We have to empirically learn how one thing leads to another by experiencing the world’s regularities—associations and patterns in event. This made Hume an empiricist.

Hume’s regularity theory is a controversial stance because it goes against all of our intuitions. Is this not a case of philosophy going too far? Take Dave. He might use his empirical knowledge of the world to claim that we do cause things to happen: it is self-evident. ‘Look’, he might exclaim, ‘I am going to cause your nose to bleed by punching you straight in the face’…

[Punch] (cause)

[Nose bleeds] (effect)

But a cause, C, might simply be an event which precedes another event, the ‘effect’, E, in time and space. Dave just predicted his bodily movements accurately and ‘causation’ just describes a relation between conjoined events which we have come to understand so far—cold chains of events which we have no say in but tell stories to ourselves about to make predictions about the future (inductively).

If this is all true, Dave only thought he made his bodily movements come together to punch me. His ability to predict that my nose would bleed was drawn from his fountain of associated personal experiences, while his bodily movements were ‘programmed’ for him. So while his intention to punch me was spot on with regard to the result, the control he thought he had over the movements was illusory.

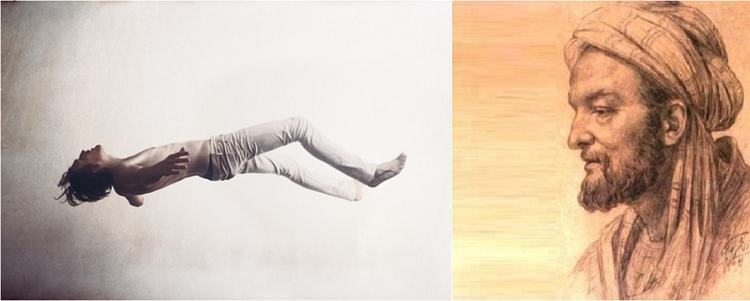

Did someone necessarily cause that nosebleed? (Island Records)

As a brief but relevant digression, I have inserted here a stance that is in contrast to the one held by Persian philosopher Avicenna of the Islamic Golden Age. Philosophers advocating a position akin to Avicenna would contest Hume’s arguments at all costs on the basis that we supposedly can possess innate notions of cause completely separate from experience. Avicenna, born 980 AD, posed the concept of The Floating Man, a man permanently suspended in air and deprived of all his senses from birth, removing the possibility of him ever experiencing anything. Yet this man, so the thought experiment goes, still knows who he is through his ‘knowledge by presence’—primordial knowledge of oneself which is not dependent on biological senses or even a physical body. (Douglas Adam’s sperm whale in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy did not possess such knowledge.)

Avicenna thus postulated the existence of a transcendent self or ‘soul’, which is born outside of experience. I am sceptical. How does The Floating Man know who he is? Is he anybody? If he was suddenly gifted with senses, would he be able to see objects (e.g. humans) like we see them from theirs shapes and their behaviours? Unlikely. Photons of light would reflect from an object’s surface into his eyes but he still has no learned perspective of what he is looking at, until now, to form a picture. Would he be able to predict what an action upon it would lead to? Even more unlikely. He requires experience to appreciate anything.

'Then let the subject consider whether he would affirm the existence of his self. There is no doubt that he would affirm his own existence … And if it were possible for him in such a state to imagine a hand or any other organ, he would not imagine it to be a part of himself or a condition of his existence.'

New ideas are conceivable, according to Hume. However, these ideas are still constrained by the experiences we have already had. Take Hume’s take on unicorns (‘virtuous horses’):

A virtuous horse.

Ideas are impressions of other objects we have interpreted somewhere else in our lives. We can conceive of unicorns because we have formed impressions about horses and horns and rainbows and they have coalesced in our imaginations. Moving back to Dave, he might have seen red stuff coming out of his own body following physical impact before; or, possibly, he might have read about nosebleeds in a book or seen one in a Hollywood action movie. Either way, he gained a relevant understanding of objects in the world such that he could predict what would happen when his swinging fist met my nose.

This idea ambiguates what objects are real, in the usual sense of the word, for, as subjects, we determine their realities. Thus unicorns are real, just like horses; fictional characters are real, just like our friends; gods are real, just like forces of nature. Both objects in each case can provide truth and meaning in our minds.

Objects, such as unicorns, then, are only deemed extraordinary because we are unable to align our thoughts with them. One day if we find that we can account for their existence, unicorns would lose their mysticism (the downside being that other people would consider us insane). This idea pertains to all kinds of beliefs, say, regarding our physical abilities. As Hume stated, this places our minds at the centres of events we ordinarily take to be causally related:

Kinds of 'cause'

When we recognise regular successions of events we project our narratives—wills, intentions, motivations—onto the Universe. Events are constantly unfolding around us—chains of conjoined events which are contiguous in time and space. These sequences are apparent to us only because we view them subjectively as ‘necessary connections’ to make sense of them consciously.

In terms of causation, we believe we ‘cause’ events to unfold because we ‘will’ them to and, subsequently, we understand the results. Like my typing on the keyboard now—I sense I am causing words to appear on the page, using my knowledge of the English language and laptops, and I make sense of the words that do appear by providing the necessary connections between all the events, such as the necessary finger movements (hopefully with few errors). Naturally, we do not hesitate to call the first the cause and the second the effect by this associative connection—but it is our minds which create this inference since human experience is rooted in its own empiricism. I, therefore, believe it was me who caused the right words to appear on the page.

Take three kinds of ‘cause’ we notionally take to be real but are arguably just associations of ideas which we connect using our own intuitions:

- Resemblance: See something happen and assign it a cause (e.g. the fact that I believe I can cause this door to open is only a result of enacting certain movements before on similar doors).

- Contiguity: Expect something to happen because events usually precede other events (e.g. Pavlov's dogs were conditioned such that they salivated when they heard a metronome usually preceding food; similarly, a fear of non-white people has ingrained itself within my psyche because the only non-white person in my school was a bully).

- Cause-effect: Posit a cause (e.g. sleep is affected by the presence of a full moon; even if people's sleep does reduce, a full moon is an extremely unlikely cause).

In each case there is only an idea of a true cause in our thoughts. What makes it harder to give us causal power is that our thoughts might be conveyed to us by the Universe—entailed with other events in one long chain (E1, E2,…Ex), deterministically or indeterministically.

Relations between fundamental components of our universe (e.g. ionised gases emitting radiation when 'excited' in certain ways, constituting the pattern seen) can be used to be explained this beautiful nebula. In this way causation is real. The same underlying physical relations might govern human behaviour too. Or, perhaps, a god with a trident dictates what happens supernaturally. Either way, there would be no 'us' acting behind our 'actions'. (NASA)

Possible worlds

Let us take a different approach to defining causation by turning to possible outcomes across different worlds. By theoretically probing what outcomes can occur, we can explore the nature of causation in more detail. Specifically, we can understand it through the limits of possibility.

I might, for instance, believe that swinging my cricket bat against a window will cause it to shatter. However, even if the glass does shatter, I cannot claim that I definitely caused it to shatter: there was a chance this would not have happened. We ought to then think about it shattering in terms of a possibility.

Did I use this implement to cause the glass to shatter? Am I just a physical object too but conscious?

In a more-extreme example, I might, counterfactually, postulate that my pen will not fall to the ground due to gravity when I release it from my grasp. Someone could argue that there are real versions of reality where this is possible. There are no logic guarantees to the contrary since it cannot be logically guaranteed of what will happen in the future; we only know, in retrospect, how something occurred in the past, where we use this information to infer the likelihood of certain outcomes. Hence there is always something probabilistic about conjoined events—between cricket bats and smashed windows, pens and Earth, and more—as counterintuitive as that first seems.

During our lifetimes, in our own experiences, we see enough of the same thing to know when to expect certain outcomes since we can associate causes with effects. Our worldviews are built on such experiential assumptions. We place the most confidence in future events which stem from the most likely events, in accordance with explanations we have constructed for the sake of our understanding. A scientist develops evidence in exactly the same way. Particle physicists at the Large Hadron Collider, for example, announced the existence of the Higgs boson to the world only when they saw it with 5-sigma (99.9999-%) certainty. This finding was used to validate the Standard Model theory. However, even scientists, in line with scientific method, can ascertain their descriptions of things with statistics—in this case to affirm the laws behind things smashing together. But their statistical certainty only expresses confidence by removing levels of impossibility.

We can never be sure, then, that causation is anything more than constantly conjoined events when we analyse anything empirically like this. Even if we come to see a regularity of events 100 % of the time (e.g. my pen falling towards Earth’s core after I release it from my grasp) my predictive power would only be directly relevant to the times I saw this regularity in the past. A claim to the contrary requires an inference—a generalisation about what will probably happen in the future. We would have to repeat the experiment infinitely-many times to prove the truth of the hypothesis (e.g. that pens always fall towards Earth’s core released from one’s grasp above Earth’s surface’). But ‘infinitely-many times’ is, by definition, unobtainable: it is a human construct used to define something we cannot reach. Therefore, we should transfigure our understanding to appreciate all kinds of possibilities and recognise that we infer causation between events through necessary connections we hypothesise.

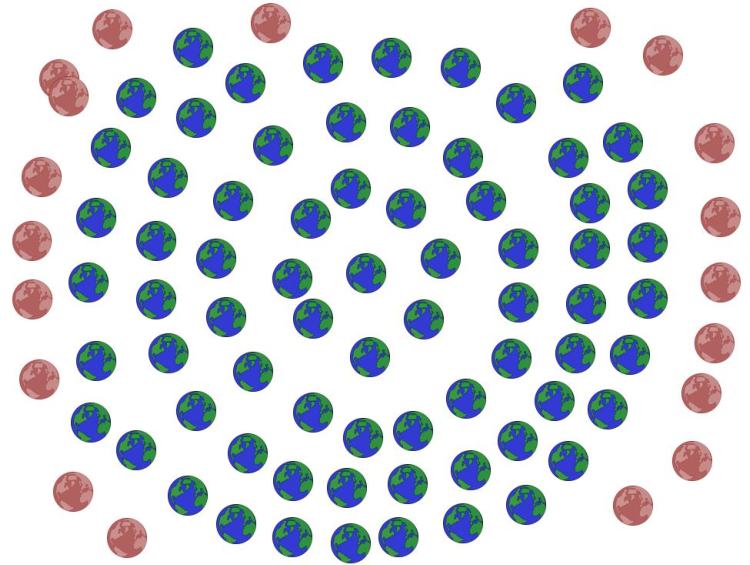

For any given event many different permutations—many alternative states of affairs—could have actualised instead. Each has its own degree of likelihood. Do we need to stretch the realms of reason as far as abstractly possible (to infinity) so as to conceive of actually impossible worlds (red)? Say, could an electron be an elephant if the Universe metaphorically evaporated before recombining? Perhaps this is possible.

Counterarguments

Hume, as discussed, believed that we contrive ideas of causation from personal experience. However, his views demand that the human mind cannot possess innate knowledge for it to begin existence as a blank slate. But Hume would have been intellectually obliged to accept new evidence which suggested knowledge was innate to humans. This is exactly what some studies suggest.

One such study (Muentener and Carey 2010) purports to show evidence of innate knowledge in infants. More than a summation of learned experiences from their surroundings, the authors claimed that the infants were able to expect certain things to happen, suggesting that there is a bodily origin to how humans make predictions, meaning we genuinely possess causal insights into the physical world from birth, akin to Avicenna’s ‘knowledge by presence’. Some animals, like chimpanzees, too, have been shown to use notional senses of causation to generate creative plans of action (Kohler 1925). If these arguments are correct, Hume’s entire stance would be undermined, for humans could be credited with knowledge outside of experience. As such, we could claim that we are capable of exerting control over objects in the external world and not be limited to cognitively holding impressions of them and watching things move around us, so to speak. If, however, these experiments are instances of scientists demonstrating incorrect conclusions, Hume’s position would not be undermined. The jury is still out on this one.

Are they figuring out the world or, in part, do they already know it?

Conclusions

The arguments against all human causation being a necessary connection between constantly conjoined events are compelling. While we can be quite sure an ‘effect’ will follow a ‘cause’ from experience, without ever possessing innate knowledge of what can happen, without ever having certainty, without ever being free in action, we cannot truly claim to possess the power to cause anything. What staggering implications this view holds for our intuitions.

Bibliography

- Hume, David. 2008 [1748]. Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Jonathan Bennett.

- Kohler, Wolfgang. 1925. The mentality of apes. New York: Harcourt.

- Muentener, P and S Carey. 2010. Infants' causal representations of state change events, Cognitive Psychology, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 63—86.