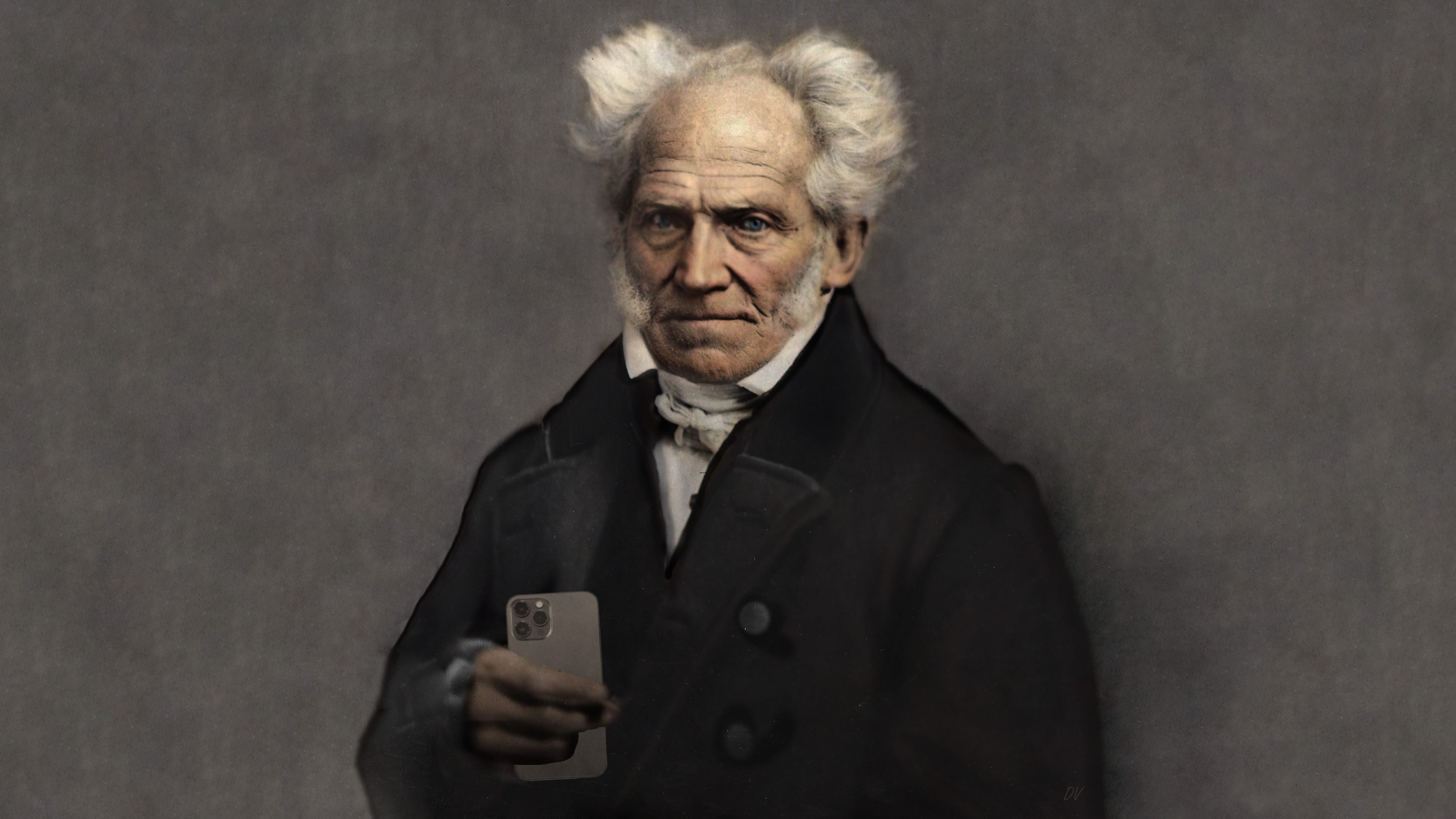

Schopenhauer on Social Media

Artwork by Dijana Vilić.

In 2021, deep into the Digital Age, we are seeing social media play a central role in the way we lead our lives. It is prudent to ask whether its influence is broadly a positive or a negative one.

What are our motivations for being on social media? How does it affect our happiness? Does it detach us from inward experiences and lead us towards outward pursuits of happiness? Of what priority should we consider validation from other people?

For some potential answers, let’s look to the warnings of philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (b. 1788). (Yes, you read that correctly: Arthur Schopenhauer.) Specifically, let’s pay attention to his 1851 essay The Wisdom of Life.

Why was he so wise?

In The Wisdom of Life Schopenhauer discusses three concepts of happiness: 1) the happiness that comes from within ourselves, i.e. from our inward perceptions of things and sensual experiences; 2) the happiness that we receive from property and material wealth; and 3) the happiness that we receive from the validation of others through concepts such as honour and reputation—or, in the terminology of 2021, ‘likes’. Let’s focus on the last one because it’s obviously the relevant one.

On people who feed into pursuits of honour and reputation, Schopenhauer writes:

In Schopenhauer’s eyes, if you’re of high honour and reputation in society, then with these may come things like increased security from the people of the town, and extra Christmas cards. But what are honour and reputation, and why should we value them? They are merely the contents of your self-perception which others have helped draw for you. They have no bearing on your true character (assuming you have such a thing) and the thoughts that come from it.

To briefly discuss the term ‘vanity’—Schopenhauer goes on to explain that vanity is the constant pursuit of external validation. Someone may post a topless selfie on Instagram; why are they doing this? The same question applies to the people of 1851 who coveted more Christmas cards. Both root their self-esteem to acceptance from others. They want to feel somewhat fulfilled from its validation. Their vanity is attached to it; it feeds off of it.

Likes for validation. (Getty)

Was Schopenhauer onto something way back in the 1850s? In particular, ‘considering the picture they present to the world of more importance than their own selves’ feels strongly applicable to life in 2021.

Who really goes on holiday, or runs a marathon, or even makes themselves a nice home cooked dinner if it is not shared on social media? Who even has a baby or enters a relationship if it is not on social media?

Surely, it’s time to reclaim these events and moments, enjoying our inward perceptions of things and sensual experiences without distracting ourselves with the urge to project these to the external world.

On the other hand, perhaps there is something positive to take from our pursuit of validation, from seeking high honour and reputation. Regardless of the means by which we pursue validation, reaching it gives us a sense of fulfilment, and that may not be a bad thing, at least not in itself. And aren’t we all at least a little bit vain?

Holidays and photos have come together since cameras became accessible. (Photo by Artem Beliaikin on Unsplash)

Sentiments against novel aspects of modern life aren’t exactly a recent phenomenon, either: society’s resistance to change is a tale as old as time, which might explain our negative judgements towards social media. Inevitably, fear dwindles over time as people slowly accept the changes as ‘normal’. For example, television was met with hostility due to the still much held worry that it turns people into ‘couch potatoes’; the hostility relented. People were scared of microwaves and other forms of radiation; they then embraced using them.

Much further back, Socrates refuted the then ground-breaking technology of the pen in Ancient Greece. He was certain that the only effective way to communicate was face to face, and that knowledge could not be effectively transferred any other way.

Today people will strongly oppose even small changes. For instance, they will vehemtly complain about the addition of features to operating systems and oppose changes to the user interfaces of social media platforms.

Back to the main point—should we not celebrate social media’s ability to bring people together and share ideas and experiences? Especially in light of a pandemic, it is a vital communication tool for people all over the world.

In spite of this counterpoint, if Schopenhauer was alive today, I doubt he would really say we are ‘living our best lives’. Neither would I.

It is time to hit the stop button and start taking pleasure in the simple things in life again, being in the moment and reaching to our own inward experiences for enjoyment rather than external validation.

Maybe go to that gig and sing along to every song, soak up the atmosphere, and leave the phone in your pocket off. Or, more realistically, start with waiting until you get home to post your pictures.