The Philosophy of Working Out: A Personal Trainer's Perspective

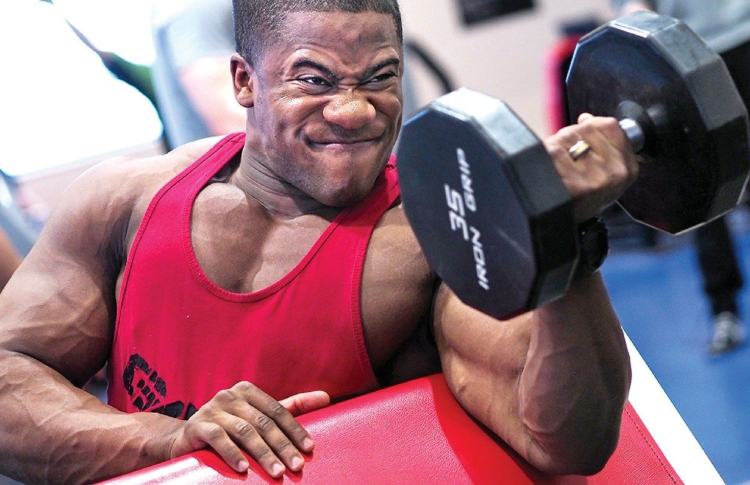

Featured image: Personal trainer Will Clayton.

Recently on The Human Front we dissected the topic of adversity. We asked, how should you react to hardship in your lives? One option, it was argued, is to apprehend the very problem that holds you back and to use it to fight for something.

Such a personal battle represents an individualistic journey of overcoming; of defeating that which aggrieves you. The underlying message was about constant growth: continually identifying hurdles and overcoming them in a constant but meaningful struggle.

A reader got in touch with The Human Front because they had an emotional response to this message—not because they necessarily lived their moral life pitted against adversity like this but because they had already appropriated adversity in another way by tenaciously training (working out) in the gym. How, I wondered, was going to the gym a reaction to anything other than a manifestation of one’s desire to be healthier, to perform better, or to be notionally more sexually attractive?

After I thought about this for a little while, I appreciated that there’s a relevant story to tell here about existentialism and adversity. It features a subject, their adversity, and a self-defined way out of it, whereby their body imposes limits which are the objects of the subject’s overcoming.

I went to interview the subject to gain a greater insight into the process.

The interview

Hello. I hope you’re well. Give the readers of The Human Front a summary of who you are and what you care about.

‘My name is Will. I’m passionate about music, I love almost all sports, and I follow a vegan diet.

‘I went to school in Winchester (Hampshire, UK) and studied psychology at the University of Sussex. I worked for a little while in the field of psychology after university. The original plan then was to go back and do a master’s degree via a practitioner’s education route. But after I went travelling things changed in my mind a bit. I started to make different kinds of personal decisions. Then, for one reason or another, I ended up in the fitness industry.

‘Although my ears aren’t to the ground as much as they were five to ten years ago, psychology still has a massive impact on my thinking—even on how I approach training.’

What do you do for a living exactly?

‘I work as a personal trainer and I’m an assistant club manager at the gym I do that in. I’ve been in the fitness industry for six or seven years now.’

Do you have any interests in philosophy?

‘I’m quite an introspective person. I think we all can be. I tend to like scratching beyond the surface of things. However, I don’t really read much into philosophy academically. I did study Freudian psychology, which touches on the selfish, innermost instincts of human motivation, which I still find interesting; and I studied falsification in philosophy of science, which still affects my thinking.’

What was your reaction to reading ‘Appropriating Adversity’?

‘I think the human reaction to adversity is a great topic. I think many people who read the article will find it agitating—but in a good way because of the relevance to it has to their lives.

‘Maybe this is the psychologist in me speaking, but we’re all human so our reactions to adversity will be quite similar. The points in the article were actually quite comforting. I related to choosing to fight for something instead of running away from it; I think hope can be our weapon.’

Why is training an important part of your life?

‘Fitness was something I already found really appealing before I embarked on a career in it. I came from a physically active family and, as I said, I love sports. But fitness increasingly absorbed my other interests. Something about it made me want to grow.

‘I think fitness is something which can, theoretically, inspire anyone. We have intimate relationships with our bodies because they embody our physical spaces in the world; and because we can nurture them, we can grow them in ways we see fit. That’s what I do and I feel it’s important to encourage people to have some of those benefits, too. We can look all after ourselves better and we each get to decide how.’

Physical training takes willing people to extreme levels.

What is your approach to training?

‘I’ve found adopting a philosophy that grew out of my interest in psychology. When I’m in the gym I’m obviously aware I’m physically training; but now I acknowledge that I’m psychologically training as well. I intentionally set things that are out of my reach. When I achieve them physically I feel the physiological benefits of accomplishment.

‘This approach is a bit dualistic—even detached and disembodied. I see my body as this thing from the outside. I also see what my irrational mind finds motivating and what will drive it the most. I design training programmes accordingly.

‘Like anyone, I naturally find some aspects of training more appealing. I specialise in strength and conditioning. I focus on particular aspects within these areas while growing slowly outwards into other areas with patience and self-discipline.’

Does your restraint extend to outside the gym?

‘Veganism is a massive part of my life; of my identity. It gives me purpose to be compassionate by giving me another worthwhile fight.’

How do you set yourself goals?

‘To push my mind away from impatience I generally think it’s essential to set achievable goals. They should be simple but not so easy so as to be light work. Whatever your end goals are, a realistic perspective makes growth more likely and, in the long term, discourages us from plateauing or simply giving up.

‘So I think growth should be an ongoing process of chipping away at ourselves. The journey is a continuous fight for more growth, not resting on our laurels when we suddenly hit a big goal.’

When did your motivation become serious, almost obsession-like?

‘My motivation became serious when I realised fitness could have a positive influence on the rest of my life.

‘Setting goals provided me with lessons: that when I pursued milestones that were previously out of reach, hitting them would be validating. I could define where I wanted to be and find the power to get there.

‘I like finding new ways to reach new goals within a structure. I accept that it’s fine for some levels of performance to be unobtainable right now. It’s not defeat because I know I can work towards these levels and reach them eventually. I’m regularly humbled but having this attitude gives me more motivations; I tend to want more challenges as soon as I’ve finished one.

‘In many areas of my life I now breathe a realistic but hopeful perspective. My self-discipline has been really rewarding.’

Can you point to any adversities in your life that drove you to start behaving like this?

‘There are many factors, really. The main one, I think, though, is the competition I had with my two older brothers when I was younger. One is two years older than me and the other is four years older than me. From a really young age we were competing, whether that was through gaming or some kind of sport, and I think I was really affected by the mismatches in physicality between us. They were always quite tall for their ages and I was quite small for my age; I felt like the odds were stacked against me all the time. When playing rugby or basketball, for example, I felt quite disadvantaged.

‘But I don’t think I ever accepted my deficiencies because I don’t think I ever quite accepted that I should ‘be fine’ with losing. Sure, I was generally competitive. I could have gone into a competition for who can jump the highest and been five-feet tall competing against someone who was six-feet tall and still be annoyed that I lost. But there was something deeper underlying this nature that I wanted to overcome. I’d always get suckered back into competition and lose again. But 5 minutes later I’d rise to my brothers’ again.

‘This attitude I carried was just this weird thing that stuck with me throughout my childhood. I was always fighting something and losing almost always reinforced my behaviour.

‘The rewarding thing from all of this, though, was that every time I repeated a task, I improved. I bettered myself. I used my adversity to grow—grow in strength, fitness, and skill—which was a tough lesson with great rewards, as with many things in life.’

Will after completing an ultramarathon.

As a personal trainer, what kind of frameworks for growth do you provide to other people?

‘I try to constantly move the goalposts for my clients. This requires upping targets slowly to encourage realistic development. It’s a fine balance, though, because making the client too comfortable will inhibit their progress to the extent their physical training becomes stale, static, and boring. I also have to logically work within the limitations of their physiological adaption.

‘Personalised training programmes are best. However, my clients often aren’t that sure of what they want, exactly. Often the motivation is there, somewhere, and, as a trainer, it’s my job to strategically find it. But, ideally, my personal training gives them the confidence to become a bit more introspective and then more autonomous with time.’

What kind of goals do people have?

‘Whatever the biggest personal motivation is, I think it should be tapped into and exploited the most. It seems obvious but it’s not a given because people assume there are set ways of doing things.

‘I’ve learned first-hand that nothing is concrete. People’s goals can be anything, from shifting a bit of bodyweight after Christmas to offsetting major health concerns such as high cholesterol or high blood pressure.

‘I also try not to drop bombshells on them. We have egos and often can’t see far beyond what we do already. We all have our own hang-ups and insecurities, our own pace of doing things, and our own preferred workouts. So I suggest new things to each client. But this is their process; their journey. I’m leading them to their own conclusions. I’m just trying to show them that their goals are achievable.’

Are many, if not all, people driven by insecurity? Are they fighting inescapable cycles of adversity where they surround themselves with suffering?

‘Many people do come with insecurities, naturally. For example, they can have body-image issues or more-morbid concerns about their health. Battling these insecurities can be sobering and can create adversities in themselves. Still, all I can try to do is guide people to their own empowerment, whereby they become more accountable to themselves. I’m not suggesting that everyone should actively fight their insecurities; but if they’ve turned up to the gym, there’s hope because they’ve already started the battle—and it can be a very rewarding one.’

Thank you.

The Human Front's reaction

I, too, love pushing myself physically. In my case I go to the gym to improve my physical performance for specific sports. I’m sure there’s some vanity and health concerns imbuing my motivations as well.

In Will’s case I can identify adversities that triggered him into action. He reacted with proactivity and discipline and humility and persisted with relatable resolve. This attitude spilled into other areas of his life, such as into his food choices, on his ongoing journey of improvement.

But I think there’s a greater motive here beyond physical exercise. Our adversities can inspire us; and, in the name of personal growth, with an appetite for change, and with a desire for empowerment, we can face the adversities in our lives head-on. And, so, we will be enthused into a life of meaningful progression, wherever it is we choose to go.