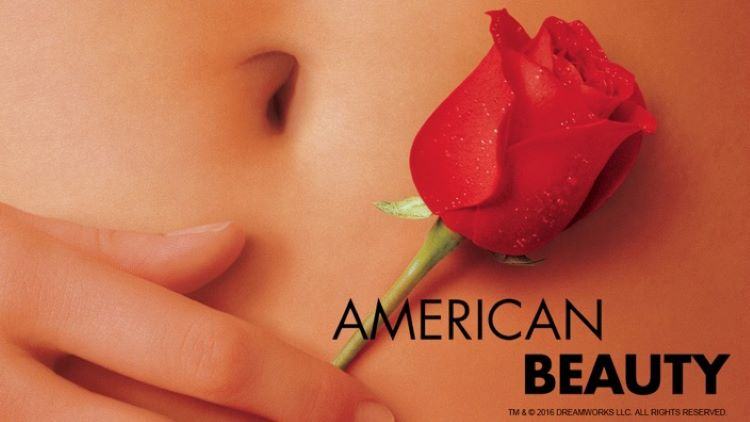

The Philosophy of American Beauty

Featured image: In American Beauty (1999) roses symbolise façades of outer happiness. Not everyone is happy to live behind them: they want to face life with existential honesty, peering into an oftentimes-bleak reality to find out who they really are. And in one middle-class, leafy suburbia, there's about to be an awakening. (DreamWorks Pictures)

Sam Mendes’ American Beauty (1999) not only touches our nerves but singes them. The film is about a sexually frustrated father, Lester Burnham—played by Kevin Spacey, no less—becoming infatuated with his daughter’s best friend. Lester is subsequently hit by an existential crisis, which leads him into making a number of questionable decisions as a father, husband, and employee. American Beauty is a stunning black comedy which satires his misery. The film was well received by critics, who were duly generous with their awards, and rated highly by cinephiles around the world.

A significant amount of existential philosophy is written into the film’s narratives and, as drama unfolds, we, too, begin to ask ourselves what the hell we are doing with our lives. As we turn the camera to ourselves we are prodded and provoked enigmatically. Are we living miserable existences? Will we embrace life honestly or will we awkwardly put these questions to the backs of our minds?

American Beauty is an uncomfortable watch but for all the right reasons. Here’s to the philosophy that makes it so.

A humdrum suburban life

Husband Lester (Kevin Spacey) and wife Carolyn (Annette Bening) recklessly expose their teenage daughter, Jane (Thora Birch), to a number of ugly marital scenes in American Beauty (1999).

The Burnhams—father Lester, mother Carolyn, and daughter Jane—live a quintessential middle-class life in a friendly suburban town: their large house is fronted by a finely mowed lawn and a white picket fence and furnished with a bed of red roses. Everything, from the outside, is perfectly functional.

However, though their lives are coated in ideas of success, no one in the family is actually happy.

Lester and Carolyn’s marriage is a joke. Their terrible relationship and their bad parenting have collectively fostered a toxic environment for Jane, who wants out of the family as soon as she can. They neither respect nor like one another, a fact which is made more obvious by their dull and quiet surroundings. Individually, they are all depressed. Their relationships fundamentally fracture them from their independent needs.

Instability sits at the nucleus of the family. In the end, all it takes to capsize their lives is a single vibration of sexual desire …

Turbulence

Lester Burnham: 'I feel like I've been in a coma for the past twenty years. And I'm just now waking up.' Lester's fantasises about his daughter's best friend, 16-year-old Angela Hayes (Mena Suvari).

Lester’s reality is the first to be shaken in the family as he becomes infatuated with Jane’s best friend, Angela Hayes (Mena Suvari). Angela is a cheerleader at Jane’s school and, during one of her performances, Lester completely loses himself in sexual fantasy. With it, the first foundation of the happy nuclear family—the strong, loyal, immovable man of the house—is shaken and the devolution of the family unit rapidly advances from this point onwards.

Prior to setting eyes on Angela Lester was performative in almost all aspects of his life. He has lost his sense of self (that is, if he ever had one). His smiles are only notional; his successes symbols. He works every day; but he hates his job. The family eat together in the dining room every day; but no one enjoys it. Carolyn, Lester’s wife, is a selfish bore (like him), and his daughter, Jane, resents him. And he resents them. So it doesn’t take much of an insight into Lester’s life, then, to appreciate its true mediocrity.

Lester’s life wasn’t always this bad, he says, but it’s got to a point when something has to change. In a middle-class slumber he has lost himself. He wants to start directing his life again. He wants his individuality back. And the introduction of Angela provides a disgraceful catalyst, which spurs Lester into some kind of a disturbing upturn.

Revolt

Lester, much to his wife's dismay, bought himself a remote-control car (and a real car too) with the money he blackmailed from his employer. His clear disunification was sparked by his sexual attraction to a young girl. But his pain was beckoning him to rebel before that, only he was latent. Now Lester is ready for the spice of liberation, whatever the consequences.

Existential philosophers often speak of people revolting against their situations (or something similar) to overcome a lack of meaning in life. They suggest we take the fight to the world, which has accustomed us with its norms, and rebel with character to live with a sense of purpose, born from autonomy and authenticity, to fill the void.

Revolt is precisely what Lester seeks to achieve. Upon meeting Angela he learns what she likes in men. His work- and family-centric drives are given up and replaced by motivations towards attracting Angela. His desires are clearly immoral—raw and animalistic—but they unshackle him from the weight of a dispassionate and apathetic life which was directing him into roles that made him feel unimportant and forgettable. He could have held an important role in his family, at least. But his wife, who he still finds attractive, emasculates him: she doesn’t love him, despises his weak will, and prefers mantra and self-help audiobooks over his company. But Carolyn is dry and boring and poisoned by her own perfectionism. She is disingenuous and guarded, showing no genuine care for others. Janes suffers most from this deprivation of love and attention, calling her parents freaks, signalling patriarchal and matriarchal collapse in her life.

Facing his abyss, Lester is ready for revolt. He is willing to sacrifice his marriage and his job for the life of a lonely bachelor, inverting his current values and replacing them with older ones. He buys tacky things, smokes weed, and gets a low-paying job at the drive-thru he worked at 18 years prior. He works out and drinks shakes. He retraces his life and reverts back to the last point he felt things were on his terms after years of disappearing; he’s too cowardly to create new solutions. Lester regrets his years lost to obedience to the ‘American Dream’ and he is ready to return to embrace much-simpler, much-more-disreputable, and much-uglier truths. For at least his existence would be honest.

Hence much of American Beauty is about rebellion. The other main characters, not just Lester, feel the overarching weight of society’s and other people’s idealistic expectations, too. Their lives up until now have been silently miserable. But in revolt there is a chance of freedom: a moment to define where they each actually want to go in life—away from broken families, social status, masculine order, and heteronormativity and towards free and open expression.

Dread

'It was one of those days when it's a minute away from snowing and there's this electricity in the air, you can almost hear it. Right? And this bag was just dancing with me. Like a little kid begging me to play with it. For fifteen minutes. That's the day I realised that there was this entire life behind things, and this incredibly benevolent force that wanted me to know there was no reason to be afraid, ever. Video's a poor excuse, I know. But it helps me remember … I need to remember … Sometimes there's so much beauty in the world, I feel like I can't take it, and my heart is just going to cave in.' — Ricky Fitts

American Beauty’s plastic-bag sequence, augmented by its infamous score, is an emotive scene in the film. Lester’s new neighbour, Ricky Fitts—who is also Lester’s new weed dealer and the new romantic interest of Jane—narrates a moment he apprehended on his video camera: a plastic bag being lifted and dragged round by the wind. Ricky is transfixed by this moment despite its apparent insignificance to everyone else. Are we like the bag, passing through time and space, changing course every now and then, flittering, but never really in control?

The moment elicits bone-depth emotion in Ricky. He cries. It’s not immediately clear what perturbs him but he says:

On one hand, his words suggest optimism—the possibility of a wonderful existence within this beautiful world—beauty within each of us. But, on the other, there is dread—dread arising from the responsibility of having to find one’s own beauty. To be free, to be open, to be full of love—these require courage. One must search themselves blindly—take ownership and commit themselves to a beauty that might not truly exist. And while Ricky could leave his sad existence and tragic family situation behind, he would have to do so alone and exposed.

Condemned to be free

Meeting rebellion with a bleak reality.

Are we just summations of experiences? How can we be in control? What does it really mean to be free? Each main character undergoes a rebellious transformation in spite of these questions, journeying further into the unknown: Lester rocks his life’s foundations with untouched, stigmatised sexual desires and a newfound power to make decisions; Carolyn is having an affair; Ricky plans to leave home, fleeing his ex-military dad, Colonel Fitts, who internalises his traumas and doesn’t allow himself to exist, and his sick mother, Barbara; Jane is going to leave with Ricky.

Freedom comes with fear. This is all they’ve known! People now have to craft their own worlds’ meaning; and the Universe is an empty place.

We can live like Lester did before he met Angela, in bad faith, passively accepting a fate of some kind, taking little responsibility for the choices we make and dealing with the constant uncertainties of our environments; or we can take an alternative route: we can question what we’re meant to do, revolt against it and build essence into our existence by searching or rediscovering our true selves. But does a true self really exist?

Before an awakening in American Beauty the characters find it easy to perform according to expectation. When shaken they are compelled to break free. To quote Rosa Luxembourg: ‘Those who do not move, do not notice their chains.’ They must escape somewhere to define their place—to sketch purpose with the vibrancy of individuality atop dreary and superficial worlds—but where?

This question screams the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre, according to whom ‘Man is condemned to be free’.

Sartre’s man transcends in revolt. But, because he is ontologically rooted in what made him, his existence is stricken by a fraught ambiguity. While he can find freedom, it will come at the cost of being terrified: of feeling torn and isolated from the world. Total responsibility is now his.

Yet, while the burden of freedom and responsibility is nauseating, quite possibly, it’ll be worth it.

To be heard; to be free

Lester reflects on the sad invisibility he's been cloaked in until now.

Thus American Beauty begs for revolt: can we be validated for who we really are? Lester was subdued by his own choices but retransforms himself and shows us what we are capable of, too.

Towards the end of the film we witness a touching exchange between Lester and Angela:

LESTER: [smiles, taken aback] God, it's been a long time since anybody asked me that. [thinks about it] I'm great.

Having had a sexual encounter with a 16-year-old girl which restored his self-esteem, being on the brink of divorce with a cheating wife, after he is fired and professionally rid of all responsibilities … Only then is Lester visible to the world: his existence recognised but his life torn apart.

With this saddening awakening we see Lester give himself the opportunity to restore himself, to test where he could go, in order to pursue happiness with existential honesty.

Lester only reached this pivotal point of existential crisis through self-destruction. He had to transform who he was—nobody—to try, possibly in vain, to become someone. Yet the prospect of embracing questions so fundamental—of wilfully choosing to be terrified by the responsibility of freedom—induces dread. But, through the life of Lester Burnham, we learn that, with a push, the fate of ignorance and inactivity is the destruction of self.

Tread carefully. The question lingers.