Philosophy as ‘Great Art’ - an Interview with Sophie Grace Chappell

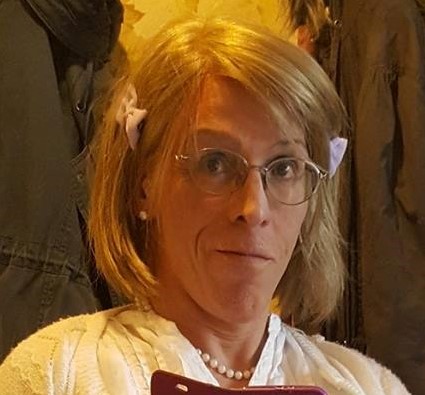

Sophie Grace Chappell, the only transgender professor of philosophy in the UK.

Today (21.02.22) I had the pleasure of interviewing Sophie Grace Chappell. Sophie Grace is a professor of philosophy at The Open University who has published over 100 articles and various books on a broad range of topics—ethics, ancient philosophy, sex and gender, literature, epistemology … Sophie Grace and I briefly worked together at the Mind Association, where she was the Treasurer and I am the Administrator. I found her pleasant and insightful and was always keen to get to know her more. An interview was my finest chance.

In a wonderful interview from 2020 Sophie Grace spoke to The Guardian as UK’s only transgender philosophy professor, having published an open letter to JK Rowling, and opened up about her life. Her story is one of authenticity and wisdom; I was inspired reading it. It’s a coup to have her here.

Hello, Sophie Grace. How are you?

‘Mildly abashed by your introduction—but fine.’

Congratulations on surviving my flattery. You deserve it!

Tell our readers how you got into philosophy.

‘From the start, the questions that—I found out later—people call “philosophical” simply came naturally to me. What are numbers, really? Do other people really see the same colours as me, and how can I tell one way or the other? If you keep on repeating the question “Why?”, as toddlers like to, will you always get back to the same place eventually, no matter where your Whys started from this time? What counts as translating a word from one language to another, and why? Is there a God, and does he—or she or they—interact with us, and how, and how can we tell? How, if at all, are right and wrong connected with happiness? What makes a beautiful poem beautiful? A thing can be both a key and a lump of steel at the same time, or both a sonic event and the words “Come in and sit down” at the same time; if these simultaneities can happen, why shouldn’t something be both a mind and a body at the same time too? And so on. I was pestering people with questions like these well before anyone ever told me that they were philosophy, and that some people spent their lives pursuing them.’

Socrates would be proud of your incessant questioning, no doubt. As a working philosopher today, what are you currently researching?

‘I am very lucky indeed to get paid to think about philosophy. But I’d do it for free if I had to and could. Not a word of this to my employers’ Salary Office, of course.

‘What am I working on … this year, this month, right now? This year, I have a book to write on friendship, which I hope everyone will like. This month, before I turn to the friendship book, I am trying to finish up Trans Figured, my rather unorthodox and left-field book on transgender, which I’m sure some people will love and others will hate. I take that as an invitation to make the book even more Marmite. You might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb.

‘And today, I’m preparing for a radio interview about gender self-ID in Scotland. It’ll be on Radio Scotland on the Kaye Adams show at 1130ish today, 21.02.22. Wish me luck!’

Good luck!

Kaye Adams. (BBC Radio Scotland)

You have many interests, spanning often-disparate parts of philosophy. What part of you connects these interests? In other words, what unifies your love of the subject?

‘Would it matter if nothing did? Is there something in common between all those questions I started by listing? Does there have to be?

‘My interests in philosophy are, yes, various. But my interests in life are various. What unifies the more general interests is, I suppose, just me—as in, I’m the one who has the interests. I’m not sure there’s a lot more to it than that in the case of philosophy.’

No, I guess there isn’t.

‘I mean, the world is amazing, and life is interesting. It just is, and in so many ways. And if you explore what interests you, you do very often find surprising and unexpected deep connections between superficially disparate areas: everything is connected to everything else, like Lenin said. But unlike Lenin, I don’t believe there’s any a priori magic formula for finding the connections. Except that you need to keep your eyes and your mind open, which is the opposite of a formula.’

I note that, in quite a few publications of yours, you’ve written about philosophers of the distant past—Plato, Aristotle, Augustine … Today what kinds of things can we learn from their approaches to life when their environments were so vastly different to ours?

‘The first thing we can learn from them is this: that when thinking about history you should start by saying to yourself “Screw relevance”. I think the present-day attitude of only being prepared to study anything if it’s “relevant”, that is if “there’s something in it for us”, is a huge mistake. It’s the classroom variant of Iris Murdoch’s fat relentless ego. And the way to talk people out of it is to point out that it is even self-defeating. What’s the best thing for us, for our egos? It’s to get beyond constantly asking “What’s the best thing for our egos?” and take an interest in the world out there in its own right and on its own terms.

‘So we should look at philosophers like Plato and Aristotle because they’re intrinsically worthwhile, not because there’s some handy detachable take-away that we can apply in a committee meeting, or portentously quote on a first date—and a last one, no doubt—or stick on a cheesy meme-poster on the internet. We should take them as objects of attention in their own right and on their own terms, not as raw materials for our own self-improvement schemes. And we should fight very hard, and with deep self-directed suspicion, against our own ingrained tendency to assimilate them to our comfortable selves and our pre-existing values.

‘Aristotle, for instance, can look very moderate and humane and sensible to us in some ways, at times to the point of seeming boringly platitudinous; especially in some of what he says about ethics. But Aristotle absolutely wasn’t a twenty-first century liberal democrat, and there is something rather sophomorically myopic about appropriating the bits of Aristotle that fit our prejudices, then trying to explain away his “unpalatable views”. I keep on writing essays on virtue in which I insist on the alienness of Aristotle, on how seriously he meant the bits that people keep wanting to hush up, about women and slaves and barbarians and so forth.

‘This phenomenon of alienness is unsettling partly because it so often comes into view right alongside things that look absolutely familiar. You get this in other writers, of course; it comes up all the time, for me at least, in Hilary Mantel’s novels about Thomas Cromwell. Or take Dante, who has this marvellous passage in Inferno Canto 34, lines 10 to 15, where he uses a utterly mundane image, something that anyone alive today has seen who’s been in a farmyard in a cold winter: a rotten straw captured in half-clear yellow ice.

Here all the souls—how to say this versified?—

were deep-encased beneath that crystal skin

like pale straws in puddle-ice vitrified,

frozen for ever: some lying in their sin,

some standing upright, others on their face,

others, like longbows drawn, bent round and in.

‘You read that simile and it sends a shiver of recognition down your spine: this man was writing over 700 years ago, yet he very clearly lived in the same experiential world as we do. And then you look at what Dante uses the image for—it’s an image of traitors “frozen for ever” into the deepest depth of hell—and you remember that Dante’s world accepted the Inquisition, and burnings at the stake, and crusades against the Cathars, and crazy antisemitism, and almost constant civil war and civic violence—and hell, of course—and you are lost in bewilderment: how can a life-world so familiar, also be so foreign? Well, you get the same baffling combination with Aristotle and Plato: one minute they’re hugely recognisable, the next they’re completely different from us.

‘For sure, his non-PC views weren’t inevitable views for Aristotle—there were people in his society, notably Sophocles and Euripides and Plato and Diogenes the Cynic, who questioned them in a fundamental way. But they were natural views for him, in his time and place, and if Aristotle has a fault it’s that he idolises whatever he takes to be natural. There’s plenty to think about here, but insisting that Aristotle must really deep down just share our values will not help you to see it.

‘At the same time as all this, of course some of the ancient Greeks’ questions are exactly our questions too, and of course some of their experiences are very much our experiences too. I am just thinking today—for teaching purposes, I’m writing an Open University course on it—about Plato’s small masterpiece the Crito, where Socrates has the chance to run away from patently unjust execution, and refuses to take that chance. Why would he do that? Isn’t he letting wrong triumph over right? Is this a good way for his story to end? How can he abandon his friends and family? We read the Crito and we share his friends’ bewilderment and sorrow. And in this case there are things to learn directly, about civil disobedience, and about the citizen’s relation to the state, and about that well-known ethical test-question “What if everyone did that?” Even today this is a conversation that we can pretty much join in too, provided we stay alive to the huge chasm of time and difference between us and Socrates and his friends.’

That’s fascinating. Often I imagine transporting myself to ancient Greece, too, to watch some of these events unfold and hear what these people had to say directly. Part of me is awe-struck by what I am imagining—how different their worldviews are—while another sees people very similar to us pondering the same kinds of problems.

Okay. Now I’m going to ask you our Ten Questions. Are you ready?

‘As I’ll ever be.’

Question 1: What’s your number 1 hobby?

‘It’s really touring the Scottish landscape. Sometimes I do that on foot, sometimes on a bike, sometimes on skis, sometimes by swimming, sometimes by rock-climbing, sometimes by ice-climbing, sometimes in a kayak, sometimes on a train, sometimes, if there’s really no alternative, in a car. The constant in all this movement is the same: it’s Scotland, the land I’ve always wanted to live in, and actually have lived in since 1998. In all sorts of ways, I am so lucky to be here.

Action shot.

Question 2: You have a poster of a philosopher in your room. They are your hero. Who is it?

‘Am I allowed to say Dante Alighieri? No? Too bad, I just have.’

Question 3: An alien visits Earth. As a parting gift you give them the three greatest texts of philosophy to read on the way home. What are they?

‘The complete works of Plato; the Bible; the Summa Theologiae.’

Question 4: As you hand over the texts you explain to them what philosophy is in one sentence, hoping not to confuse them. What do you say?

We were wondering what All Of This was all about;

so we wrote down All Of That, to figure it out.

Nice.

Question 5: Who do you think the most-underrated philosopher is?

‘Someone we’ve never heard of, because that’s how underrated they are.’

Damn it: you keep catching me out.

Question 6: When do your best ideas come to you? In the shower, looking at blue sky … ?

‘When I shut up and listen. When I stop writing and read. When I switch off the computer and my mind turns on.’

Relatable.

Question 7: What fictional character do you identify with most?

‘Alice in Wonderland.’

Question 8: What’s your favourite film?

‘The next one. I love watching new films, and I don’t want to get stuck in a rut or obsess over things I’ve loved in the past, though there are lots of them—and too many to pick just one, anyway.’

Question 9: And your desert island disc?

‘It’s not a disc at all, it’s a piano or keyboard. If I have to be stuck on a desert island I want to be able to make music, not just listen to other people making music. I’m a very poor pianist, but I’ll be a much better one by the time I’m rescued, if I ever am. Oh, blast. I shall need to tune it or power-supply it somehow. Whatever.’

Question 10: You’re being forced to start university as an undergraduate student again. What are you going to study? It can’t be philosophy.

‘Forced? How would you force someone to study? Even when I was a voluntary undergraduate I didn’t study anything like as much as I should have. And I doubt I would have been better incentivised to study by anything worth describing as force. You know how it is; I just had a lot of growing up to do. As 19-year-olds do.

‘Anyway, if I stop being annoying and allow your supposition that I get a second go at the university menu—’

Thank you and sorry—

‘Then I’ll read classics again, please, and focus on the literature this time. Especially on Greek and Latin poetry: Homer, Sappho, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Horace, and Virgil. Or maybe, if there’s a degree in this, ancient and modern literature, so I can read all the other good stuff since the classics as well?’

Fantastic. Now I have a few more questions.

What’s your favourite part of being a philosopher?

‘It’s either the excitement when you realise that there’s a paper to be written, or the relief and the celebration, the yay-moment, the dancing around the sitting room moment, when you finish writing it. I like the bit where an idea emerges, and you know you have something to say but you aren’t yet quite clear what, and you have to work out how all the details go. It’s a bit like decorating a Christmas tree, or building a Meccano set: this all fits together somehow, but how? You feel frantic and smothered by the pace at which all this new stuff is dropping out of your head: when I am writing I scrawl notes and reminders to myself all over the backs of envelopes, and I have to remember to take a pen and some scrap paper if I go on a bike ride, because once the distractions of the internet stop and my mind clears, the ideas and the clues will start raining down on me. You only feel able to relax once you are reasonably sure you have managed to catch it all, and to slot it all together in the right combination in your paper.

Then someone makes an objection that brings down the whole edifice and you have to start again. Often this someone is you.

‘Or alternatively, another three weeks pass, and you’re back at the ideas-emerging stage with another paper.’

Where do you think philosophy can improve as a discipline?

‘Ideally, we should stop thinking of philosophy as a discipline at all, at least if that means as a science, or quasi-science, or pseudo-science, beset by what Freud called the narcissism of tiny differences, and pursued with pedantic competitiveness for money and prestige in a university academic-bureaucratic setting, and rigidly categorised and pigeonholed separately from all the other university departments. There’s a lovely bit in The Sword in the Stone where Merlyn explains to the Wart that hawking, like poetry and dance and music-making, is one of the Great Arts, and you can’t use magic to cheat at the Great Arts, so they have to get the Wart’s lost hawk back without using any of Merlyn’s spells. I know almost nothing about hawking, but I very much like the idea of philosophy as a Great Art. That’s exactly what it is, and there’s no way of cheating.

‘Ouch! Now, boy, flying is not merely some crude mechanical process. It is a delicate art. Purely aesthetic. Poetry of motion.’ (Walt Disney Productions/Buena Vista Distribution)

‘We can, and should, think of philosophy not, or not merely, as a single discrete pigeonhole in the Faculty Board Of Studies, but as a spectrum of big-sky humanistic explorations. And as a field of inquiry that is open to anyone to explore: under current socio-economic conditions it does help, on the whole, to be an academic if you want to be a philosopher, but at times academia gets in the way, and you really don’t have to be a university employee, or even a university student, to think about the big philosophical questions. Anyone can do it, though of course some people do it better than others: it’s all about explorations of the textures of our shared experience and reality, and of the relation between that experience and that reality. This relation is also, from another aspect, the relation between the humanities and the sciences; that’s why philosophy straddles the humanities-science divide.

‘When I say that philosophy should not be thought of as a discipline in the bureaucratic-pigeonholing sense, I don’t at all mean that philosophy shouldn’t be disciplined. Of course it should; if it really is a Great Art, it must be. Philosophy, I think, should be a loose-bordered range of inquiries that are kept rigorous, maybe even a little bit austere, by the rather different but very much complementary requirements of two things: first of logic, and secondly of a grown-up, and open-minded, and kind, and humane, and humorous, and inquisitive, and un-fanatical, and tolerant, and mature—and sensible—sensibility.

‘So there are two kinds of quality-controlling challenge in particular that philosophers should push each other hard with. One is “That is logically inconsistent”, the other is “Come off it”. In the academy today, partly because of the bureaucratic pressure to mark out research territory, we hear plenty about inconsistency, but rather less about “Come off it”. In an age of perversely brilliant research programmes, for example about whether we’re living in a computer simulation—and also, in an age of conspiracy theories—“Come off it” is an important challenge too.’

From the perspective of a white man, I feel aggrieved by the social inequality within philosophy affecting me. How does it feel to be the only trans philosopher professor in the UK? You represent an entire group! Do you feel pressure to act in certain ways?

‘Pressure? Pressure to act? Just try it. Just try pressuring me to act in any way at all. I am the most counter-suggestible person in the entire world. Tell me to jump and I say “Why?” and “No, you jump” and “What’s so great about jumping anyway?”

‘I think I’m still the only openly transgender professor of philosophy in the UK, but I know for a fact that others are coming along soon. All power to their elbows. To our elbows.

‘Do I represent an entire group? I don’t know. I’m not tactful or diplomatic or anything. I blurt. I shoot from the hip. I think aloud, and sometimes that gets me into trouble. I can’t see a cage without rattling it; I am as a rule against cages. I’m not an accredited spokeswoman for The Transes. Other trans people often disagree with me—in particular, as with my adoption analogy, they often think I’m too concessive.

‘What really is a problem that I hope to be a solution to, is the visibility problem. There are very few publicly transgender people in the UK. That makes it hard for us all, especially the trans people who aren’t out yet, and who are nervous about sticking their heads above the parapet—in the present climate, entirely understandably. This lack of visibility makes it too easy for transgender people to be monstered—we become a dark vague threat that no one actually knows, not people with faces but a “woke mob” or shadowy semi-criminalised lurkers in the Ladies’. This shows up in polling returns: people treat trans people as a menace in a way that they couldn’t possibly, if they actually knew any or had seen any on the telly. Me, for instance: menacing? Come off it. I’m about as menacing as a traffic cone. But—when will Coronation Street or The Archers get a serious transgender character? That’s what I want to know.’

In another interview you described the debate around trans issues as ‘a kind of refusal to listen to transgender people’. Often moral progress is slower than erosion. So what do real solutions look like and how can philosophy help in the long run?

‘The present UK government is about to run out of track with Brexit. It’s shortly going to become completely obvious, even to those to whom it isn’t already obvious, that except for a few currency-jockeys who have got extremely rich—and some of whom are in the UK government—Brexit is an utter fiasco. I would say “I hate to say I told you so”, but truth to tell, I don’t hate to say I told you so in the least; saying I told you so is pretty much the only pleasure that Brexit’s ever given me.

‘When the track does run out, the UK government will look for any distraction they can think of. They’re already signalling that culture wars will be one such distraction. I predicted in May 2017 that the Brexists would eventually come for transgender people. No doubt I was called a fearmonger at the time, and I admit that it felt to me, when I made it, like a slightly out-there prediction. It doesn’t look so out-there now, does it?

‘Right now, I’m sorry to say, the whole UK is pretty much Transphobe Island; the UK is way out of step even with Ireland, even with the island next door, on trans inclusion, never mind other western democracies. And one thing that can happen is for the UK to wake up to this fact, and do something about it: take a step back in the direction of equality and tolerance. With any luck Scotland will get this momentum moving later this year.

‘And how can philosophy help with all this? Well, by being itself. I think philosophy sometimes overrates its own cultural influence. Believe me, compared to Coronation Street, or even The Archers, we’re nowhere. And everyone understands that, I think, except a few philosophers who have this delusion about philosophy as the King Discipline in the real world, as opposed to Plato’s Callipolis, and get all agonised about whether we’re doing enough to “change the debate”. We should do what we can, of course—that goes without saying—but we shouldn’t be ashamed or worried of pursuing recondite questions too. It’s not either/or: there’s nothing wrong with writing about trans rights in the morning, and four-valued modal logic in the afternoon. We have the freedom to spend at least some of our time in the ivory tower, and we should enjoy it without guilt.

‘Also, we shouldn’t worry too much about our audience size. Of course at the Open University we have relatively big audiences for UK academia, but even those aren’t that big. And wherever you’re a university teacher, it is nearly always the personal encounters that students value most, and that are most transformative for them. As William Blake so wonderfully says—no doubt he’s having a dig at Bentham: “He who would do good to another must do it in Minute Particulars: general Good is the plea of the scoundrel, hypocrite, and flatterer, for Art and Science cannot exist but in minutely organised Particulars.” If I can’t have that picture of Dante, I’ll have a picture of Blake instead, please.’

Permission granted.

Finally, assuming philosophy helps with a good life, what would you say to someone who is thinking about getting into it?

‘Read, read, read, read, read. When you’re doing philosophy, reading is the petrol in the tank; if you don’t read, you’re not going anywhere.

‘And what D.H. Lawrence said in a moment of irritation and impatience with the bland, complacent moral maxims of Benjamin Franklin: “Find your deepest impulse, and follow that.”’

Nice. Thank you, Sophie Grace.

‘Thank you.’