Moral Ignorance

Featured image: Is it right to excuse people who 'didn't know any better'? This question fervently lives on in the statue debate, in which revolutionists are being accused of attempting to 'erase history' by toppling statues of controversial figures. Revolutionists claim we shouldn't glorify the achievements of people who are capable of such immorality. Perhaps, as I argue in this article, harmony between sides can be found with some nuance. How? We grant reprieve to some people but not others: to those who were incapacitated by their social contexts and neither intentionally nor negligently ignorant. (Keir Gravil/Reuters)

For how long can we appeal to ignorance to spare people in history from our negative moral judgements? This is good question which promises no clear answers. Nonetheless, there are some great lessons we can take away from grappling with it.

Our values are variegated across communities and evolve with time. What we deem acceptable in our beliefs and in what we practise is liable to change.

Time, in particular, makes fools of us. It has already dispensed with the likes of Mother Teresa and Winston Churchill, turning them into controversial figures, revered icons though they still are. Mother Teresa was ‘a friend of poverty’, living a different life to the one she preached. Winston Churchill held indefensible racial views.

Accusations of ignorance will eventually follow us, too, and we might fear that every generation, including ours, is chastised unfairly. In a train of negative moral judgement, one generation is flagellated by the next for their lack of virtue. Surely, we can be more nuanced than that.

Instead of an exercise in retroactive witch-hunting, we should want to sharpen our criticisms. For some people have genuine excuses for their ignorance. Their behaviour can be better understood when it’s relativised to their social contexts. They may deserve the benefit of the doubt. Others do not.

The task is not a simple one. It boils down to figuring out what standards we ought to judge people by across time, what lines we separate the blameful and the blameless along.

We need a sense of legitimate moral ignorance to trim our judgements accordingly. But what counts as legitimate? Some philosophy follows.

'I had no idea!'

Of course, on many accounts, some things just are immoral. What makes something immoral now made it immoral in the past, too: morality persists across ages. People shouldn’t be excluded from our retrospective determinations of blame if they were committed to these things. They lived with completely different expectations to us, sure, but it’s not necessarily the case that they couldn’t have figured out right from wrong with trivial efforts of thought.

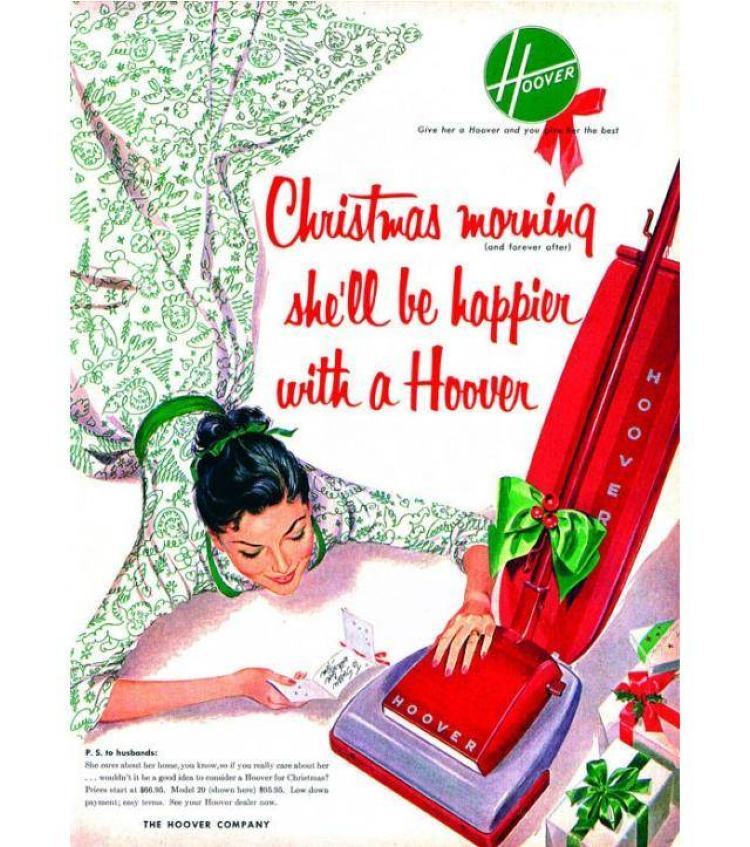

Looking back into the past, what will future generations view as archaic and be disgusted at us for? Will moral relativism provide us with an escape route from the responsibility of our present beliefs? Or will people defend us with, 'Values were just different then'. This line doesn't work now for the likes of racism and slavery of centuries gone by. What about subtler and potentially-more-pernicious ideologies such as corporal punishment and ingrained gender roles within a household of the 20th century? (See more distasteful Christmas adverts here.) (Hoover)

We, too, maintain practices of impoverished morality. We compartmentalise our thoughts for convenience.

Specifically, what are we to blame for? Perhaps someone from the future will label you a savage for eating innocent animals, selfish for jetting off on frivolous trips abroad via environmentally damaging airplanes, and backwards for asking your partner to take your surname in marriage. Are you really doing enough now to ensure your ways of living are less contemptible than Mother Teresa’s and Winston Churchill’s in the eyes of more-woke people in the future? One day you may be revealed as a villain and toppled into a local river.

Ironically, all of these potentially immoral practices make me want to point the finger less. Something is going wrong with our judgements: they are debilitated if they are given out so easily.

If you were born in the 17th century, like slave trader Edward Colston (whose statue is in the process of being toppled in our featured image), perhaps you wouldn’t have deemed it too controversial that someone such as Colston was engaged in the slave trade, given all the good things they did for your community. Your current views are bolstered and protected presently by the values that surround you but those values may not survive time’s passage.

However, we absolutely shouldn’t give people, like Colston, easy rides for their unscrupulousness. With plausible levels of scrutiny, people are capable of overcoming the urge to commit bad deeds but choose not. We have to expect more than that. We cannot always permit the appeal, ‘I had no idea!’ and let ignorance reign. We should avoid judging people disproportionately (i.e. examining the past through the lens of current contexts) but we should recognise that lenience is also destructive and that the way in which we discuss those figures now matters.

From generations of bad deeds, then, we shouldn’t necessarily deduce that people deserve less blame; rather, we might deduce that humans deserve more blame and need to make themselves better!

If we assume that there is a line to draw around the impermissible, we still don’t know where to apply it exactly once we introduce context. Philosophy may help us find some clarity through some less-woolly concepts.

Disappointment over blame

Miranda Fricker is willing to afford moral reprieve to ignorant people for their ‘structural moral-epistemic incapacity’. Basically, this is a licence to be ignorant since their access to knowledge was restricted at the time.

Fricker further argues that blame is often misguided and that disappointment is a fairer reaction, writing:

'We should carve out conceptual space for a kind of critical judgement I call moral-epistemic disappointment. This style of critical judgement is appropriately directed at an individual agent whose behaviour we regard as morally lacking, but who was not in a historical or cultural position to think the requisite moral thought—it was outside the routine moral thinking of their day … '

'Together these two proposals may help release us from the grip of the idea that moral appraisal always involves the potential applicability of blame.'

Fricker’s view, however, can seem radical. Do we really want to resist blame and sit back in disappointment for people who said and did awful things?

Consider the following examples pertaining to the beliefs of ‘intelligent’ and ‘enlightened’ philosophers:

- Aristotle (b. 384 BCE), seen as one of the world's greatest ever philosophers, saw women as subjects to men. He also deemed slaves ('living tools') quite natural.

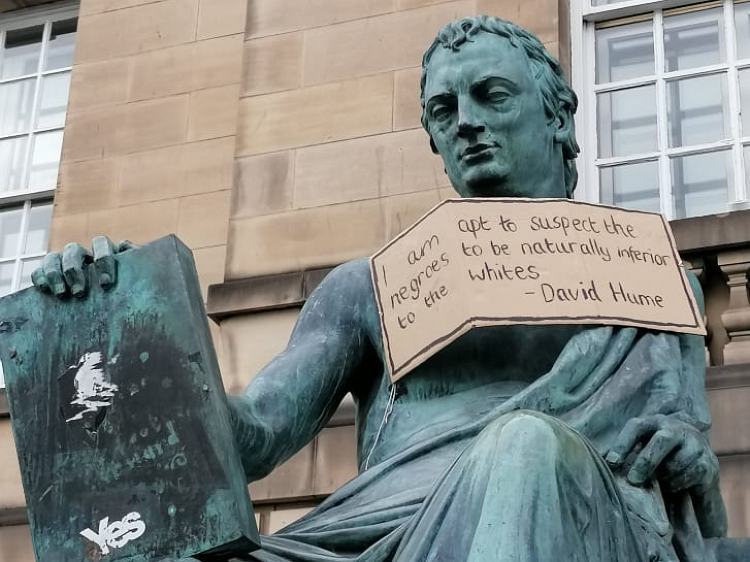

- David Hume (b. 1711 AD) was clever enough to be a university student in his tweens and to publish exceptional philosophy in his twenties. Yet Hume was a racist.

- Martin Heidegger (b. 1889 AD) tore apart the rulebooks of Western philosophy with his phenomenology of being. But, despite his intellectual capacity, Heidegger became a member of the Nazi Party.

Do we really want to save the legacies of these people with posthumous licences to be morally and epistemically incapacitated?

Perhaps not—and neither would Fricker. These men deserve condemnation for their particular brands of misogyny, slavery, racism, and Nazism. They had brilliant minds and, in at least two cases, expansive access to information resources. They were surely capable of more. Many others in their time who had much less were. So how does defending their positions, even when relativised to their time, maintain philosophical integrity? We reject their applications for ‘structural moral-epistemic incapacity’ licenses!

'I am apt to suspect the negroes, and in general all the other species of men … to be naturally inferior to the whites.' This David Hume quote was barely defensible in the 18th century. Still, some have claimed that we should maintain recorded history's nuances instead of tearing down all monumental gestures to Hume. They argue that individuals and their situations are complex and that this detail should be reflected in debate. If we misconstrue the actual events, we will create 'cartoonish' caricatures of history. I am sympathetic. But I am also sympathetic to prevalent attitudes that have been protected until today today, causing great harm and distress. (Jane Barlow/PA)

Yet there is a large sense in which we can’t be outright in our condemnation of people, even if their beliefs and actions were deplorable. For if we choose to hold them totally responsible, we condemn them to possessing levels of freedom they simply did not have access to.

But the buck has to stop somewhere. Metaphysically, humans show obvious signs of agency in what we call free will; so, ethically, we should take ownership of what is formed from that will. Moral judgements—being ‘judgy’ of people—are simply part of a functioning society through a shared sense of justice. We react with blame if injustices are committed against other beings according to boundaries we draw together. It’s not dog-eat-dog in the human world—at least, I don’t think it should be.

But, with some well-needed nuance amongst the fog of our reactions, Fricker discerns blame and disappointment. It isn’t always reasonable to expect someone to know more than they did. An important learning point for us emotionally reactive creatures, in her eyes, is to settle for disappointment and forgive them.

Permissible ignorance

Now we have distinguished blame from disappointment we can further develop what kind of ignorance is blameworthy and what isn’t. To expand our repertoire let’s look to the philosophy of Gideon Rosen.

Rosen argues that we should only blame people for their ignorance when it’s held intentionally or negligently.

Accordingly, I am not blameless if I don’t bother to read the instructions on my medicine bottle and drink myself into a state of illness: I was warned by my pharmacist to read the instructions on the bottle’s label carefully before taking the medication inside! Thus my ignorance was founded on my own poor intention not to follow orders. I am blameworthy.

Nor am I blameless if I am found urinating on a monument in the centre of London, sparking outrage, even though I had no idea what I was urinating on, for this act is negligent. I am blameworthy for not bothering to check.

But here are two more-complex examples:

- If I consent to the terms and conditions on an 887-page document, should I be held to account by the law when I contravene some terms and conditions deeply embedded in the document? The document is just so long; it's not reasonable to expect that I will read it in full and understand legal jargon—or is it? I intentionally didn't read the document and it was somewhat negligent of me. I didn't have to agree to the terms and conditions.

- If I inadvertently commit trespass during a long country walk, is the landowner's anger justified? After all, it's their land and I broke the law by traversing it. The information about their land is publicly available; even though I lost phone signal, I could have searched online for it before I went on my walk. So although I didn't intend on going on a meandering walk through private land, my poor preparation was arguably negligent and I should be made accountable for breaking the law.

I’ll leave it up to you to reach your own just conclusions. I just want to show that conclusions aren’t always easy to obtain and the result hinges on how much ‘work’ we expect people to do in each case.

Consider this real-life example: Tony Blair (right, shaking the hand of the then US President George W. Bush), led Britain to war with Iraq in 2003 based on the fictional existence of weapons of mass destruction. Did he do everything in his power, holding good intentions and avoiding negligence, to determine their existence? Thus should we blame him for his ignorance? (AFP/Getty Images)

Rosen says the bar for blamelessness is met if someone conscientiously deliberates before making their best judgement. For me this is a useful marker. However, it is only a surface-level solution: in each case we have to believe someone has properly deliberated the issues at hand; we have to decide what constitutes as conscientious; we have to determine what was enough deliberation. Therefore, a judgement will undoubtedly contain a large element of subjectivity.

Nevertheless, we have added another useful device to our moral formula, one which allows us to establish blame based on intention and negligence.

In conclusion

People held abhorrent views in bygone eras. Some of our views, too, will likely be exposed as such in years to come. How much effort do you expect from yourself?

Often we expect lots from others on the everyday level of their decision-making—unpragmatic amounts of research, sharp mental acuity, lucid rational capacity, a generous accumulation of knowledge, an awareness from experience, upbringings that nurtured the will to care about the problems we value resolving now, and so forth.

But there is a danger here that we must steer clear of: that is, we should fear relativising morality too much. If we hold nothing fixed, leaving no sign of objectivity in our moral standards, we’ll have nothing to fight for. We will indiscriminately forgive people in history; we won’t be able to challenge practices we deem immoral across cultures in the present; and, moving forwards, we won’t be able prevent moral collapses in their nascent, instead choosing to stand idly by, accepting fully fledged moral relativism.

In 'Bend Her', a Futurama episode from 2003, Bender, a robot, transitions into a robot woman, Coilette (pictured). It has been argued that the episode is transphobic since the creators exploit trans-person stereotypes, using mockery as an instrument of humour. Should they have known better? Or can we let them off the hook, granting that their early-noughties attitudes were at least partially absorbed from their surroundings? (20th Century Fox Film Corporation)

That being said, we have to admit that each person exists within a different context, each with different pressures to hold certain beliefs. In their shoes, in their microcosms, with the same incentives, we may have made the same decisions.

Determining what is a reasonable level of agency for a given context is key to determining what cases of moral ignorance are legitimate. In practical terms, we should ask how easy it was for a person to have reached alternative ideas to the ones we’re criticising them for or to have acted differently. In philosophical terms, we should ask whether a subject is a moral agent who was capable of the rejecting norms they internalised as acceptable from their surroundings. These questions fail to bear tidy conclusions. But we have learned some key concepts on our way.

Fricker points to structural moral-epistemic incapacity: a retrospectively given licence to be ignorant based on restricted access to knowledge, for which we should be disappointed, not judgemental. Rosen points to absences of intention and negligence in an acceptable form of ignorance. These notions, I think, are helpful. Others have developed other ideas across ethics and political philosophy.

But these notions cannot be applied precisely to individual situations. How much agency they each had in forming their beliefs and acting on them sits at the crux of the issue. But that doesn’t mean we cannot make our positions more robust with stronger philosophical foundations.

We should be careful not to allow the loudest people to dominate the narratives for us (e.g. demagogues in the media). So, to conclude, let’s promise ourselves this: we will form judgements as independently and rationally as we can with awareness, conscientiousness, and understanding. Once we have accounted for our own ignorance, only then, can we judge theirs.

But—oh, boy—bad people have said and done terrible things without becoming ‘controversial icons’; and I, for one, will not be an apologist for them. So I want to be clear: while we should be careful not to dish out culpability for historical ignorance willy-nilly, we should also not be afraid of bringing more things to light and amending the history books accordingly, with greater speed, impetus, and reflection.