Medical Science: From Fiction to Fact

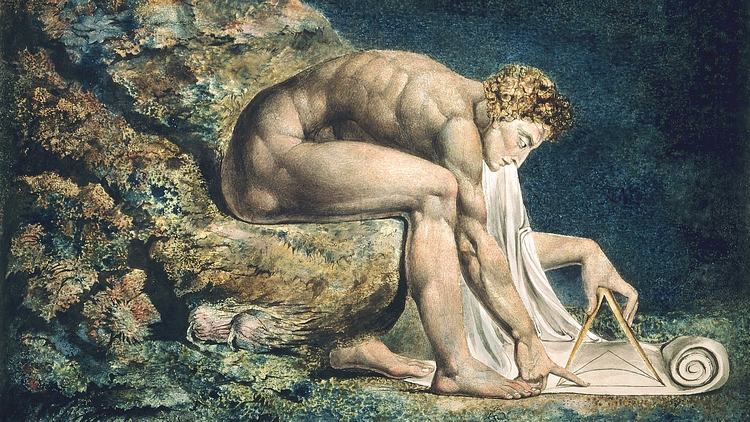

Featured image: Newton (circa 1800) by William Blake. Blake mockingly portrayed Newton at the bottom of the sea, preoccupied with his reductive, scientific approach and calculations and oblivious to the God-created beauty of nature around him. In a separate work, Blake denoted: 'Art is the Tree of Life. Science is the Tree of Death.'

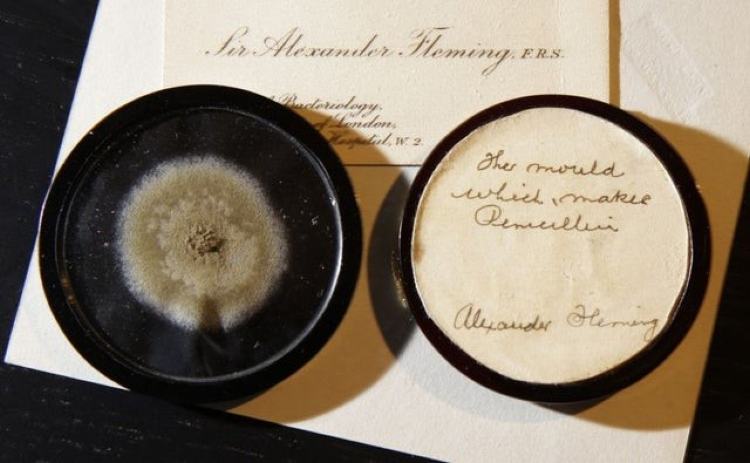

Science is fraught with chasm-wide history gaps wherein hypotheses which are made but don’t prevail are never heard about again. In medicine, much of our discoveries and advancements are down to chance, luck and political will. For example, the animal blindly selected by Axel Holst and Theodor Frolich to study scurvy was fortuitously one of the very few species of mammal that cannot produce their own vitamin C (guinea pig); Luis Pasteur discovered virus attenuation as a method of vaccination creation because his lab assistant left virus broth out for longer than intended, inadvertently vaccinating chickens against cholera instead of infecting them; and the mould from which we synthesise penicillin was only discovered to have antibacterial properties because Alexander Fleming went on a two week holiday after accidentally contaminating a staphylococcus culture plate.

Some leaps and bounds in scientific advancement were only made possible by happenstance and coincidence, and some through the active challenge of established doctrines. What do they teach us about scientific progress?

Trusting science

‘Science is amazing,’ people exclaim. ‘I fucking love science,’ people declare. Tropes of scientists emerge in popular media but primarily in only one of two ways: the benevolent knowledge seeker who aims to cure all ills; or the mad-eyed sociopath who seeks to destroy for own gain in societal status, fame and riches. Science thus has a reputation for being an all-powerful tool as well as a weapon.

Neither archetype is easily found in the real world but neither is absent: all scientists want to do good, however ‘good’ is measured; and all have ego which fuels their desires for permanence and the permanence of their work. Accordingly, brilliant scientists have developed ingenious cures for deadly diseases as well as atomic bombs for widescale decimation.

We all hold scientific beliefs. We refer to current scientific claims as ‘facts’, using the terms ‘theory’ and ‘truth’ interchangeably on occasion. We cement ‘best-fitting’ scientific claims, which are founded in ‘most-plausible foundations’, all too keenly. We also have a way of arrogantly celebrating the present and deriding the past. We sit on the shoulders of giants who came before us. Of the times that came before them, we speak of ‘dark ages’, ‘middle ages’, ‘loss of knowledge’, ‘stagnation’, and ‘lack of progress’. We describe the times that came after as ‘renaissance’ and ‘enlightenment’.

This is the modern narrative. They had no answers, we do. They had religion, we have science. They had their facts, we have ours, and ours are right and theirs are wrong.

'It had been the mere plaything of nature, when first it crept out of uncreative void into light; but thought brought forth power and knowledge; and, clad with these, the race of man assumed dignity and authority. It was then no longer the mere gardener of earth, or the shepherd of her flocks; it carried with it an imposing and majestic aspect; it had a pedigree and illustrious ancestors; it had its gallery of portraits, its monumental inscriptions, its records and titles.' — Mary Shelley, The Last Man

Steps in the evolution of medical science

Medical science has undergone many mutations to get to where it is now. In a long chain, it started from herbalism and rose to magic, to humorism, to miasma and theory of filth, and, finally, to germ theory: a theory that infectious diseases are caused by microscopic organisms with biological incentives to reproduce and spread. But now we have germ theory, we understand, we know, for science led us here. Right?

Herbalism came first. Ancient people used plants and their fruits and flowers to treat ailments. Plants have chemical properties—active ingredients—which can affect the human body in favourable ways, as can be well intuited by anyone who is an avid tea lover or coffee drinker. Quinine is extracted from the bark of cinchona tree and used to treat malaria; willow bark relieves pain; echinacea is still commonly used to fight colds; St John’s wort is used to treat depression. Herbalism is thus the first recognisable attempt at medicine, which was utilised for centuries.

Magic followed herbalism as a medical doctrine. The rise in deities for purpose of explanation facilitated the embracement of the supernatural. The chief scholar of a Babylonian king wrote The Diagnostic Handbook, a medical book of symptoms, prognoses and supernatural remedies such as incantations and exorcism rituals. It remained the primary diagnostic text for thousands of years. Other nations had their own equally enduring texts: see Egypt’s Ebers Papyrus and London Medical Papyrus, India’s Ayurveda and China’s Huangdi Neijing.

Humorism, though it predates Ancient Greece as a thought, was first formalised by Hippocrates and his followers. It postulates that the human body works through four vital bodily fluids—phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile—which are in balance in a healthy individual. If one fluid becomes dominant or insufficient, the person becomes unwell. The treatment approach of the era was, therefore, to re-establish balance through bloodletting and through diet. Galen of Pergamon, a Roman physician and philosopher, explicated humorism, writing The Art of Medicine, which became the go-to collection of medical texts for the next 1300 years. Subsequently, Avicenna of Persia, a polymath and a philosopher, wrote The Canon of Medicine in 1025 describing contemporary medicine of the Islamic Golden Age. Medical teaching in Western universities all around Europe was based on these texts; humorism became affirmed, immovably, as the obvious truth which held for a total of two thousand years.

Miasma, the theory of disease-spreading bad air—air filled with particles of decomposed matter—followed as the next most-obvious truth from the 1500s to mid-1800s. The shift from humorism was facilitated by the plagues which decimated populations worldwide in regular intervals, the height of which was culminated in the Black Death, killing between 20 % and 60 % of the European population. Bouts of plague, smallpox, malaria, yellow fever, measles, cholera, influenza and typhus accompanied the increase in global travel, demonstrating either the wrath of God, else that diseases were able to spread in ways which humorism could not account for.

The Triumph of Death (1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder: a scene depicting utter destruction as Death commands its armies from his horse, destroying the living without exception. Themes of death and helplessness were common in medieval art and literature.

Germ theory replaced miasma and is the current principal theory of infection. According to germ theory, microorganisms cause infectious diseases as they invade and reproduce within human hosts. This was first demonstrated by Louis Pasteur, a scientist and a businessman, through fermentation, then scientifically proven by Robert Koch, a physician and microbiologist, who, in 1876, demonstrated that a species of bacteria was the causative agent of anthrax in sheep. All else followed from this.

The zig-zagged road to prevailing thought

'One sometimes finds what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on Sept. 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I guess that was exactly what I did.' — Alexander Fleming. This quote would have you believe that Fleming conducted an experiment and all the world changed in an instant, when, in reality, his discovery was ignored by the scientific community for years, largely due to Fleming's terrible communication skills.

The fight for a theory to be accepted, followed and embraced is eternally an uphill battle in science. And, when it does prevail, it can be usurped like its old-fashioned predecessors.

The foundations for germ theory were laid when microorganisms were confirmed to exist. They were observed by a Dutch businessman, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who developed his own microscope lenses for the purposes of inspecting the fabric sold in his draper shop. His lenses were so good he could see unicellular organisms in rainwater, which he found endearing and wrote to Royal Society in London about. His discoveries were met with scepticism and many wished to confirm what he saw by observing these organisms themselves. But Leeuwenhoek was protective over his lenses and refused to send them to London. He kept writing letter after letter, until they sent delegates to visit and confirm his observations, and the Royal Society officially acknowledged the existence of microorganisms, ‘animacules’ (‘small animals’), in 1677. Similarly, in 1720, Benjamin Marten, an English physician, suspected tuberculosis could be caused by ‘minute living creatures’.

The intuition of contagion, the spread of disease between organisms, was already well exploited in warfare (see how the Tartan army hung plague-ridden corpses over the walls of Caffa to infect the citizens fleeing to Italy in 14th-century and British troops presented blankets laced with smallpox to Native Americans as ‘gifts’ in 1763). Further, people with leprosy were shipped to leper colonies and stripped of their possessions and shunned from society for life. The first vaccinations took place from 1796 onwards, when Edward Jenner demonstrated that infection with cowpox—which is a very mild and often-asymptomatic infection in humans—grants lifelong immunity to smallpox, a gnarly and deadly disease in humans. In 1854, John Snow traced the source of cholera infection to a single water pump, demonstrating that contaminated water can cause disease.

Two and two could have been put together to infer germ theory at least 200 years prior. Why weren’t they? Are they being put together now?

It is easy to see where the sceptics were coming from: germ theory certainly doesn’t explain autoimmune diseases, cancers, illness of the mind, cardiovascular diseases and genetic disorders. Sexual transmission of syphilis and gonorrhoea were recognised, but they were connected to morality and god’s punishment. Sepsis was considered a natural part of the healing process which (sometimes) resolved on its own.

Spontaneous generation of organisms from non-living matter, a theory established by Aristotle which hypothesised that disease and parasites come into being in dirty environments, also slowed the acceptance of germ theory.

What would the need be for a novel explanation when Jesus and humorism, hand in hand, could explain every ail without bringing animacules into it?

Humorism, the theory of humans’ four vital bodily fluids, still makes sense intuitively: symptoms of disease, poisonings and injury manifest externally, but arise from within, as the body seeks balance through vomit, diarrhoea, bleeding, coughing.

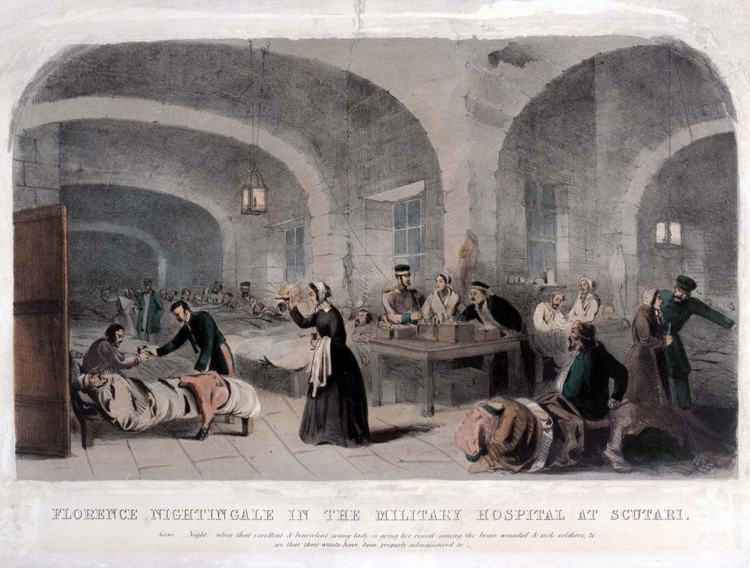

Florence Nightingale, the ‘founder of modern of nursing’, upheld miasma even in the face of John Snow demonstrating that contaminated water caused the epidemic of cholera, not ‘bad air’.

Miasma makes sense, also: corpses make the air smell foul and if, for example, you spend much time with your deceased loved one who succumbed to the plague, disease will enter through your nose and you will fall ill with it too.

Further, if there is an omnipotent deity which put all this here, they too made disease and could unmake it: let’s invoke their name and win their favour so they rid of it.

'The specific disease doctrine is the grand refuge of weak, uncultured, unstable minds, such as now rule in the medical profession. There are no specific diseases; there are specific disease conditions.' — Florence Nightingale, paraphrased in Eras in Epidemiology: The Evolution of Ideas. This quote is misused and appropriated even today as anti-vaccinators and homeopaths with no medical training uphold it as their truth and seek value in it, even though Florence accepted germ theory in the 1880s and advocated for it thereafter.

All these theories can follow logical steps to arrive at not-necessarily-true conclusions.

So when Ignaz Sammelweis, a Hungarian physician, noticed that the number of patients who died in childbirth could be drastically reduced by having the doctors who performed the deliveries wash their hands after handling cadavers in the mid-1800s, he was mocked. He was humiliated so severely, he suffered a breakdown and died shortly after his admission into an asylum. Surgeons at the time even referred to their operating gowns as having a ‘good old surgical stink’ for years after. Antiseptic methods were not implemented into hospitals until after Joseph Lister demonstrated and published the effectiveness of spraying surgical instruments with antiseptic spray between surgeries in reduction of sepsis and gangrene rates. His experiments took place only after Pasteur’s and Koch’s.

Were the physicians and scientists of the time wilfully ignorant? Were they too egotistical and narrow-minded or were they simply … stupid?

(Erroneous) certainties

No. They weren’t stupid! In fact, they were not that different from us: they were born and raised under a doctrine that was considered to be fact-producing by their eras’ experts. Medical science works on a conviction that the fundamentals are accurate; it builds upon them enormous systems of work which are based on observation and logical explanation of these observations. But these methods don’t necessarily always find truth. Shaking the foundations to bring about shifts in doctrine takes centuries. Our attempts to claw our way forward are persistent: we get closer to truths with reproducible data that imbues confidence, but we do this without ever knowing what truth really is.

Furthermore, resistance to change isn’t always unwarranted. Scientists such as Antoine Béchamp, a bitter rival of Luis Pasteur, was a fervent denier of germ theory and even proposed his own alternative, ‘terrain theory’, preaching that germs come to a diseased body as scavengers, not as causative agents. John Brown, a Scottish physician, proposed in 1780 that bodily disorders are results of too much or too little excitation. Franz Mesmer believed all living things possess invisible natural force which can have physical effects and can be used for healing. Count Mattei invented Mattei cancer cure and peddled the idea that cancer can be cured by bioenergy contained in plants. These theories came from experts, but they are all patently wrong.

These scientists held to their untrue theories as firmly as Sammelweis, Pasteur, and Koch held to their true ones. To demonstrate this even further, in pure frustration at being ignored, some even resorted to self-experimentation, with mixed accuracy. Jonas Salk volunteered himself and his family to test the new polio vaccine when he developed it: it worked. John Hunter, an 18th-century physician, aimed to prove that gonorrhoea was an early stage of syphilis and not a separate disease and gave himself both diseases at once, believing himself to be correct, hindering medical progress in treating either. Stubbins Ffirth, certain that yellow fever was not contagious, poured black vomit from yellow fever victims onto his own open wounds and even ingested the vomit, never contracting the fever and thus erroneously concluding it isn’t contagious: it is, but it’s transmitted via mosquitos only.

So have we arrived at the final, actual truth? Is germ theory here to stay?

We have observed germs in action and thus we believe in the germ theory of disease, analysing infectious diseases in humans through its lens. All scientists who live now and conduct research were raised, so to speak, on this theory. We are as certain of our approach as Galen was of humorism, as Florence Nightingale was of miasma, as ancient Egyptians of their gods.

But what if we’re wrong again?

Where do we go from here?

Let’s do a few quick calculations on how long each school of thought remained prevalent:

- Herbalism: thousands of years (beginning of civilisation to approximately 1000 BC)

- Magic: about six hundred years (1000 BC to 400 BC)

- Humorism: two thousand years (400 BC to 1500s)

- Miasma: a few hundred years (1500s to mid-1800s)

- Germ theory: just under two hundred years (1850s to present)

Each epoch bred its own experts, wrote its own gold standards, and devised its own methodologies through rational and systematic thought. It achieved its own set of goals through the same formula used today: diagnosis, prognosis, observation, remedy.

Blind faith should not be afforded to anything. Science is a belief system, one that seeks truth and is malleable in that quest.

Still, the scientific method is the most-promising approach to physically unlocking the mysteries of life. The biggest danger and potential for stagnation comes from the assuredness that current medical orthodoxy is final. Critical open-mindedness, therefore, is crucial to ensure each next step in medical science is progressive and made quicker than the previous one.

Certainty, as we have pushed for throughout centuries, is not warranted. Though it allows for emotional relief resulting from hope, it may blind us yet to the potential of furthering truth and uncovering patterns that help us navigate this world as a species, as well as individuals.

We are closing in on the truth, whatever that may mean to us in the long term.