‘Grounders Gonna Ground’ - an Interview with Joaquim Giannotti

Smile if you love philosophy.

On Twitter Joaquim Giannotti describes himself as a ‘box-to-box metaphysician’: a reference to a football position in which hard work is demanded from the player. While I don’t usually question the hard work of metaphysicians, sometimes I wonder if they put their undoubted ability to good use.

As part of our newish drive to see what philosophers are up to and why, I invited Joaquim for an interview. My hope was that his answers to my questions would stave off my insecurities about pursuing a career in philosophy. Of course, I didn’t tell him any of this so as not to pile pressure onto him. Still, I wanted Joaquim to convince me that the kinds of things metaphysicians—and philosophers at large—worry about do hold significance. (Spoiler: he did not disappoint.)

Joaquim works as a teaching fellow at the University of Birmingham and as a research associate for the project FraMEPhys (A Framework for Metaphysical Explanation in Physics). He specialises in metaphysics, metaphysics of science, and philosophy of science. He obtained his PhD at the University of Glasgow. I am very happy that he agreed to be interviewed by The Human Front.

Hi, Joaquim. How are you?

‘Hi, James! I am good and somewhat more prepared than last year for the new teaching semester. Thank you for having me.’

Excellent. Well, it’s a pleasure having you. So I’m going to dive straight in by asking: Why philosophy? I love hearing about people’s different routes into it. What was yours?

‘I went to high school in Italy. There, you have mandatory philosophy classes. The approach was historical and not particularly appealing to me. But it sparked interests in exploring whether the kind of conceptual work of philosophers I studied could be applied to some questions I had.

‘Back then, I was mostly interested in the relationship between language and reality: How do words have meanings? How does a language shape our way of thinking about reality? What are the limits of language in making sense of the reality that we inhabit? I was happy to discover that such questions, and many others that I found extremely interesting, were the business of philosophy. By the end of high school, I was sure that I wanted to pursue a degree in philosophy at university.’

As a fellow metaphysician, what do you think the most important questions of our discipline are?

‘Tough question. Here are five:

- How can we reconcile the scientific and the manifest images of the world?

- How do we get the less fundamental from the more fundamental?

- What are the fundamental categories of our reality?

- What is the nature of modality?

- How can metaphysics help us make sense of the natural world as well as of our social reality?

‘I wouldn’t bet my money on whether these are the most important questions of our discipline. But they strike me as pretty important.’

Joaquim researches problems in metaphysics for FraMEPhys (A Framework for Metaphysical Explanation in Physics).

You must be after my own heart with passions and questions like that. I’m going to put on my sceptical-of-metaphysics hat for a second, though: be a devil’s advocate and all that. Why think there are any fundamental categories at all? And, if there are, what might these categories be and why can’t science populate our ontology for us?

‘In a Lewisian fashion, I would say that the hypothesis that there are fundamental categories is fruitful, and this is a reason—defeasible, of course—to think that it is true. It is fruitful in that it allows us to systematise and make sense of the patterns we find in our world.

‘I am sympathetic to the view that the complementary categories of substance—or property-bearer—and property are fundamental. At the start of my PhD, I would have excluded the category of relation from the fundamental ones. But these days, I am happy to include it without many reservations.

‘And science does not wear ontology on its sleeves. This is the main reason why I think that we should not give to science the exclusive privilege of writing the inventory of what there is. Of course, science has a strong bearing on matters concerning what exists. But science alone does not suffice to settle all ontological disputes.’

On social media you use the handle @nothumean. What did Hume do to upset you?

‘I heard that Hume was a racist. If true, that would be a good reason to be upset. But I decided to stick with that handle to funnily express my opposition to a contemporary metaphysical doctrine called “Humeanism”.

‘As it happens, it is unclear whether Hume would be a Humean. It is also difficult to characterise Humeanism. But minimally, as I understand it, this view says that the fundamental properties of our world are inert and freely recombinable qualities. These bear no necessary connections to dispositions or causal powers. I hold a contrasting view: the fundamental properties are modally tied to powers and enjoy necessary connections across the board. On this picture, the world has less room for contingency than one might initially suppose.’

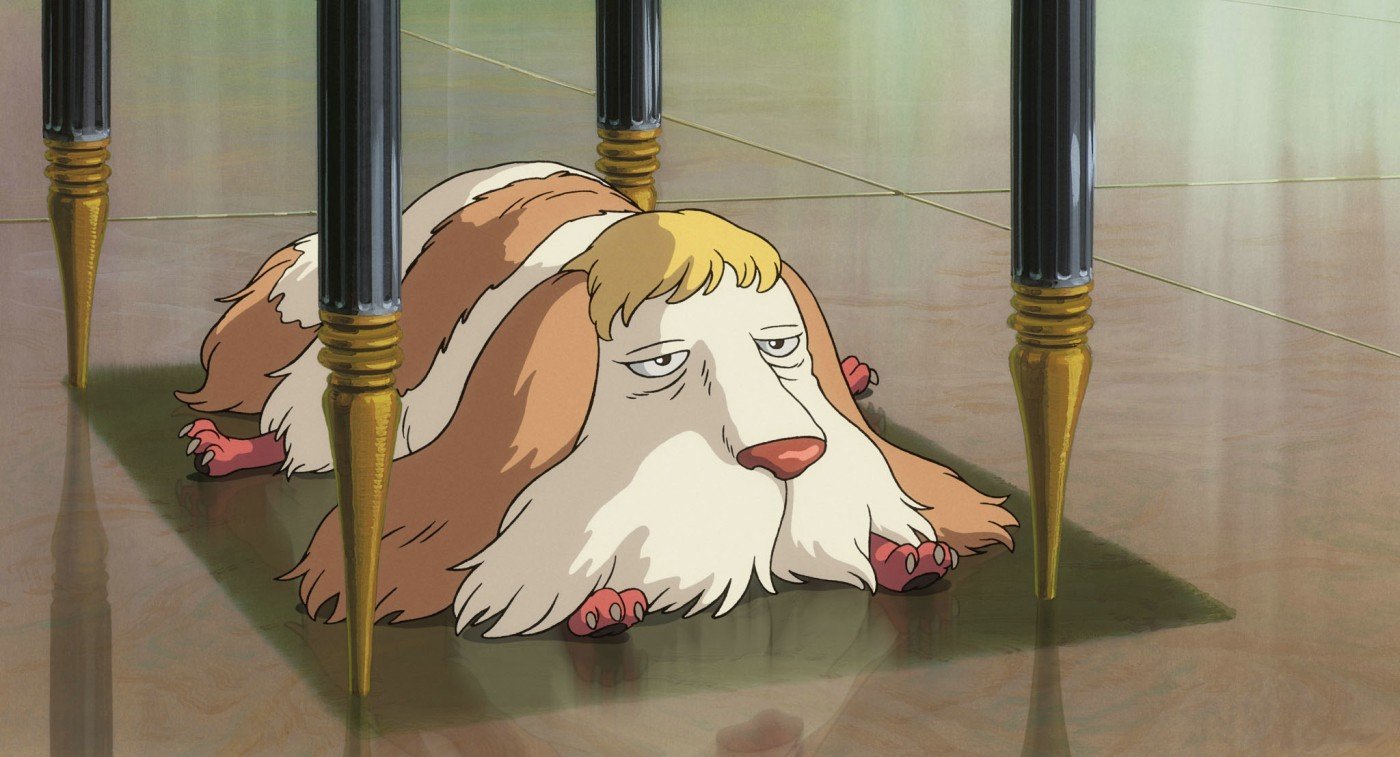

[Hume hears criticism]

So what are you currently researching?

‘My current research focuses mainly on grounding and its applications in the metaphysics of science. I would like to persuade folks of the theoretical fruitfulness of grounding in metaphysical areas of science. For example, I am preparing an article on grounding, structural equations models, and difference-making. But I am also doing research for a joint work on grounding and scientific explanation. In addition, I am drafting two chapters for different edited collections on the metaphysics of powers. I keep myself busy.’

And what do you say to the grounding haters?

‘Haters gonna hate; grounders gonna ground.’

Ha ha. Touché.

Right. It’s time to get to know you a bit. Ten Questions: let’s go! Are you ready?

‘Let’s do it!’

Question 1: What’s your number 1 hobby?

‘Weight training.’

Question 2: You have a poster of a philosopher in your room. They are your hero. Who is it?

‘David Lewis.’

Question 3: An alien visits Earth. As a parting gift you give them the three greatest texts of philosophy to read on the way home. What are they?

‘On the Plurality of Worlds by David Lewis, The Problems of Philosophy by Bertrand Russell, and The Fragility of Goodness by Martha Nussbaum.’

Question 4: As you hand over the texts you explain to them what philosophy is in one sentence, hoping not to confuse them. What do you say?

‘Philosophy is a peculiar kind of activity, whose principal aim is understanding, rather than truth or knowledge, of reality in the broadest possible sense of the term.’

Question 5: Who do you think the most-underrated philosopher is?

‘D. C. Williams’

Question 6: When do your best ideas come to you? In the shower, looking at blue sky … ?

‘When I am at the gym.’

Question 7: What fictional character do you identify with most?

‘Heen from the movie Howl’s Moving Castle.’

Heen is a dog. (Toho)

Question 8: What’s your favourite film?

‘Spirited Away.’

Question 9: And your desert island disc?

‘Burial – Untrue.’

Question 10: You’re being forced to start university as an undergraduate student again. What are you going to study? It can’t be philosophy.

‘Economics.’

Awesome. Thank you so much for this insight into your life.

I now have a few more questions. I’ll start with your passion for weight training. Apart from coming up with new ideas in the gym, do this world of yours and philosophy ever cross paths?

‘In many ways, they do. As with philosophy, weight training demands a steady commitment, discipline, a critical attitude, and a willingness to compromise. If you want to make progress in weight training, you must challenge yourself and your limits. As I see it, this process is somewhat structurally analogous to that of making philosophical progress.’

I like that.

By the way, what football team do you support?

‘AC Milan.’

Iconic. (Getty Images)

What’s your favourite part of being a philosopher?

‘The intellectual gratification of knowing that philosophy is a never-ending affair.’

The following is just another concern of mine; I want to see what you think about it. Why do you think more philosophers of the past—Socrates, Machiavelli, Locke, Hegel, Sartre—had prominent and influential roles in society in ways which today’s philosophers don’t? Or am I wrong? We do have the likes of Žižek, Dennett, and Chomsky.

‘I believe that it has to do, at least partially, with the way academic philosophers are trained nowadays. Academic philosophy is fragmented and parcelled. While it pushes philosophers to show evidence of impact outside the academia, the system does not really reward that. Practitioners of the discipline are certainly influenced by a tacit yet institutionalised conception of what counts as philosophy and what does not. Moreover, the academic system incentivises a publish-or-perish culture, often confined within specialist journals.

‘I disagree with the view that philosophy is valuable only if it has a prominent and influential role in society. Certain deep philosophical questions are technical and should not be trivialised for the sake of making a piece of research more impactful. Likewise, I think that it is perfectly fine if discussions about, say, the foundations of truthmaker semantics, are not straightforwardly accessible. But I do believe that philosophy would benefit if there were suitable platforms giving an opportunity to researchers for presenting their work to a general audience.’

What do you take to be a good life?

‘In my view, a good life is one which has dogs, coffee, philosophy, and someone special to share these things with. But more seriously, I think that the goodness of a life, whatever this means, is supervenient upon other things. But I am still undecided about what these things are.’

Lastly, assuming philosophy helps with a good life, what would you say to someone who is thinking about getting into it?

‘Be patient; philosophy is difficult. And you should keep in mind, as Kit Fine puts it, that

Nice. What a way to close.

Thank you for doing this.

‘Thank you.’