Life Is a Beautiful Contradiction (Awakenings)

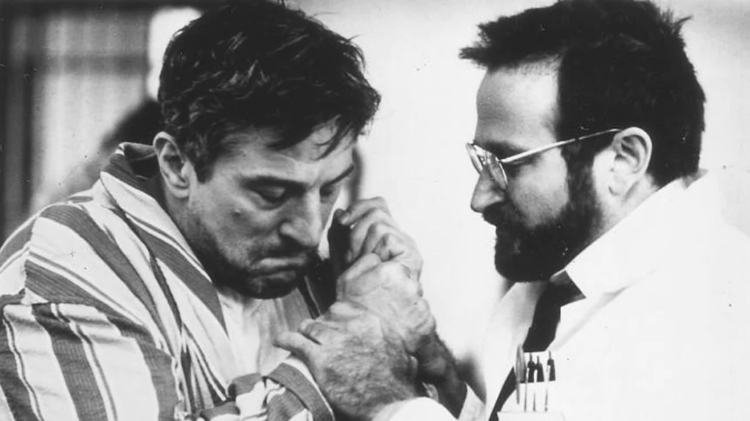

Featured image: Dr Malcolm Sayer (Robin Williams) consoles patient Leonard Lowe (Robert De Niro) in drama film Awakenings (1990). Awakenings is a commendably accurate retelling of a true story. Socially awkward Dr Sayer (Oliver Sacks in real life) is tasked with treating a group of catatonic patients who were mentally inactive for decades following the onset of a disease. Precariously, this offers hope to them and their families. (Columbia Pictures)

Eleanor: 'It's given to and taken away from all of us.'

Dr Sayer: 'Why does that not comfort me?'

Humanity is a gift that is destined to perish: the Lord giveth life then He taketh it away from us. Awakenings (1990) is a film which reveals the real-life impact of this God-given tragedy. However, in a slight adjustment from the standard paradigm of loss, Awakenings explores what it would be like to regain humanity after it was lost, only for it to be lost again.

When someone we love dies it is us who are left on Earth to absorb the damage. ‘Why did this have to happen?’ we ask. But there is no satisfying answer. Mourning is our existential response—an attempt to spare ourselves the unshakeable pain caused by irreversible loss—but, still, they are simply not with us. We can look to something spiritual to tell us they never left but this is a dangerous act of denial in the sobering face of reality.

But what if we could bring someone back from the dead? This is what Awakenings shows us by digging deep at the irrational hope we hold that someone we love isn’t, in fact, gone. Based on true events, this is a story of people coming back to life.

At a psychiatric hospital in the Bronx resides a group of patients who survived the 1917—1928 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica, a disease which attacks the brain to leave the victims ‘statue-like’. The patients are mere husks of beings in their severe stupors, experiencing little or no quality of life. Approximately five million people were affected worldwide, around a third of whom died from it.

Dr Malcolm Sayer was adamant that new drug L-Dopa was worth trialling on his patients. But this was his purely scientific perspective. How would the families feel? Hope lied dormant before the L-Dopa trial. Whilst their outlooks were modest and realistic, they were able to physically cling onto their loved ones, who were safe from untested intervention.

L-Dopa would turn their worlds upside down. Families knew that if it worked their lives would be immeasurably happier; however, like many clinical trials, the drug offered a chance, not a promise. Investing hope into L-Dopa only for it to fail would force them to rediscover old wounds while creating new ones. Fear was released back into their lives.

For a short while L-Dopa was a success. Patients were being revitalised by the medicine, families were reunited after many irrevocably lost years and compensated for by potential futures together.

Awakenings captures one of life's deep-seated themes: the value of hope.

But the success was short-lived. Practically, the patients, who were now old, had to learn how to cope with bewildering new times, decades after they were young, conscious, and full of verve. They also had to relearn how to live whilst possessing little physical and social autonomy.

Wasn’t the untouched, ethereal world the patients lived in every day, in their apathetic stupor, better than sunken hope and unknown side effects? The downfall could be brutal. Hope invites danger, for it gives us something that can be torn away. Whilst life wasn’t exactly happy before, the families at least knew what to expect.

This is where Awakenings teaches us not to be so nihilistic. Hope is our lifeblood: it provides life with the valuable vitality to go on. Without something to hope for, why do anything?

While the majority of patients in the trial never regained their former lives, L-Dopa allowed some patients to experience their humanity one more time, however transient, before they fell asleep again.

The awakenings were finite. So is life: it spites hope to be unbearably cruel. However, we should appreciate its beauty, even in these little gifts of humanity. With some perspective, we should come to realise that, even at its apex, life is necessarily contradicted: being requires nothing, action springs from rest, flair emerges from monotony. In the same vein, fear is inextricably bound to hope, for what we have is worth keeping.

Life’s fragility ought to give us impetus to fulfil our projects while we have a chance to. It is a unique experience: a series of self-overcoming acts through which we creatively flourish outward from one point of nothingness to another, birth and death, where the climax is as necessary as the beginning.

One life; one chance—or, in the case of Awakenings, two.

I hold it true, whate'er befall;

I feel it, when I sorrow most;

'Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.