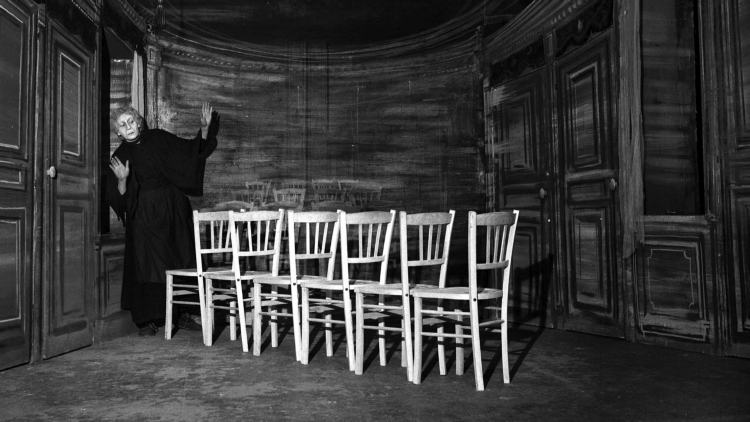

Theatre of the Absurd

The Chairs, a play by Eugène Ionesco, 1956. An elderly couple, aged 94 and 95, pass the time by telling stories. An audience assembles. But the audience is entirely composed of chairs. Is this story an indication of life's emptiness? Or, conversely, is it a satire of theatre's empty narratives?

Let us consider ‘the Absurd’. Absurdity is an apparent conflict between human’s search for meaning and life’s inherent lack of it. One may feel this intimate tug as their lives become more mechanical and repetitive, when time’s passing starts to feel destructive, and when an acute sense of alienation from other people and the world begins.

However, is the Absurd a useful concept for describing key existential moments of our lives? One could argue that it is merely a flashy term paraded by moody philosophers who have experienced severe bouts of angst and seek to make it profound. Or perhaps there is something comparable in their existential crises, something coherent we can relate to; and perhaps the use of the Absurd in drama can help us understand, for the Absurd has been explored many times before in theatre.

Albert Camus once said the Absurd, as a feeling, arises when ‘appetite for the absolute and for unity’ meets ‘the impossibility of reducing this world to a rational and reasonable principle’.

But perhaps Camus overstated our capacity for crisis as something so lucid. Maybe absurdity is little more than another romantic upsurge happening at times when our minds are most fissured: something existentially weighty but fundamentally incommunicable.

One answer, which brings the two together, is found in the poignant words of late theatre critic Arnold P. Hinchliffe. Hinchliffe argued that it took a while for the arts to finally recognise absurdity but when they did we were able to convey our fate with stronger but still-empty conviction:

Perhaps those moody philosophers were right after all.

What do you think?