On Forms of Violence and Our Relation to Them

Featured image: This article explores the fundamental problem of violence and how we manage our violent impulses. (Bēhance)

Violence … we feel it, see it, experience urges of it, use it in speech, and even display it in silence. From playgrounds to the planet, on small and big screens and in everyday life, violence pervades our lives. We are horrified, fascinated, and mesmerised by violence whilst simultaneously trying to distance ourselves from it.

We like to think violence is out there, rather than in us. Is that really true?

If we are afraid to acknowledge our own violence, then one of the ways we manage this is to repress such aspects of self. But, as Sigmund Freud famously described, the repressed will return in some form. In that case what might we look for to show its existence? And what of the less-physical, less-visible manifestations—can we spot violence in all its forms, including the more-hidden and the subverted?

In popular culture

As recently as 2015 the phenomenon of coercive control, described in one article as a form of ‘intimate terrorism’, has been included in criminal legislation as a form of violence. But, overall, it would seem we have had some difficulty in bringing psychological violence to light. We are made all too aware of physical violence.

One example of coercive control was highlighted in Patrick Hamilton’s famous play from 1938, Gas Light, where the husband engineers his wife’s experiences only to subsequently deny their reality.

In another example Tennessee Williams illustrated both physical and psychological violence in his 1947 play, A Streetcar Named Desire, as did William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which offers a dramatic connection between ambition, power, and violence.

Art and literature, then, often effectively portray the fundamental problem of violence in the human condition, inviting us to examine violence for ourselves, even if we cannot quite put our finger on our sources of strife.

In Fyodor Dostoevsky's gripping tale Crime and Punishment an impoverished Raskolnikov treads a precarious line between his rage at society and his conscience. Does his remorseless murder detail the gross limits of individual freedom in all of us? (Source)

Meanwhile, in everyday life many of us have seen a colleague, public figure, or company rise to the ranks by killing off any ethical considerations that might impede their trajectory. What might this tell us about our seemingly more-benign ambitions and what we will sacrifice to reach them?

So can we really live without violence, or is this notion a utopian dream?

It might appear that there is no solution to the problem of violence. Indeed, the psychoanalyst Paul Verhaeghe (1999) maintains that our drives are inherently violent, while Friedrich Nietzsche believed violence to be essential to life. But, even in such cases, as I hope to point out in this article, there are antidotes to the repression and return of violence that involve integration and creative expression.

Forms of violence

Slavoj Žižek (2008) identifies violence under two categories, which he labels ‘subjective violence’ and ‘objective violence’.

Subjective violence refers to direct physical violence.

Objective violence is less visible and within this category Žižek makes two further distinctions: ‘systematic violence’ and ‘symbolic violence’. Systematic violence resides within the structures of society, the ‘often catastrophic consequences of smooth functioning of political and economic systems.’ This type of violence had been elaborated in detail by Michel Foucault in his genealogy (e.g. Discipline and Punish), in which he offers an intricate insight into the more-hidden, structural operations that are enacted upon both bodily and psychological states. Violence, then, isn’t always obvious.

Systematic violence does not have to be overtly intended: an unquestioning adherence to authority or established norms can implicate us, albeit unwittingly, in reinforcing systematic violence. Consider a current manifestation of the catastrophic consequences of systematic violence in the social care setting, where a following of government policy promoted the release of elderly patients from hospitals into care homes without testing for COVID-19 in the UK. This, alongside the failure to provide protective supplies to those working in this field, brought a significant death toll to residents and care workers during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic.

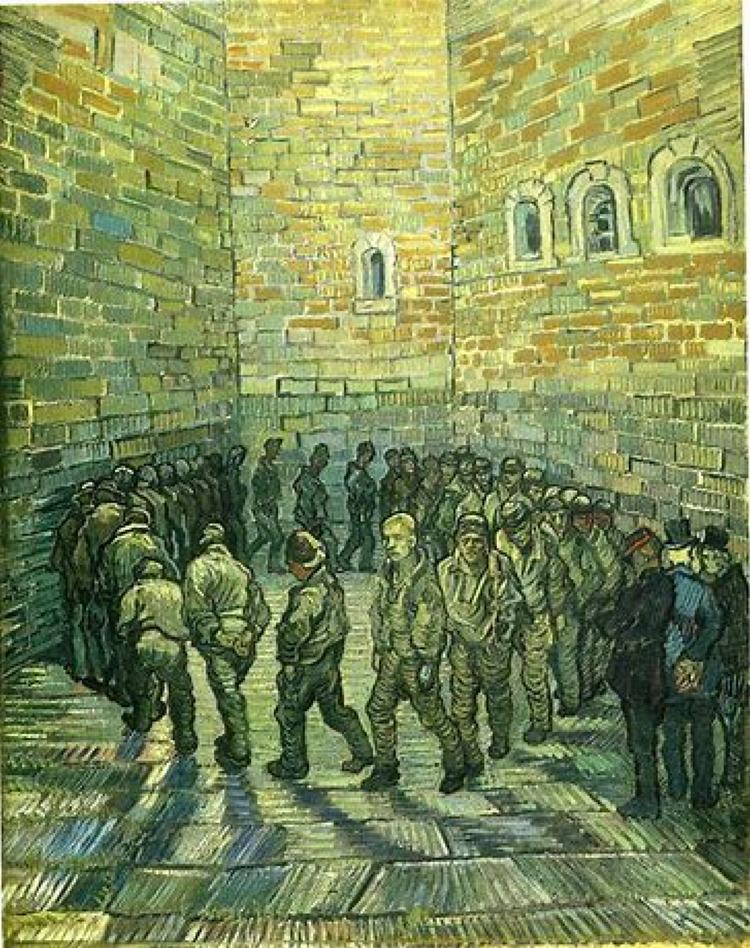

van Gogh's Prisoners' Round (1890) depicts enforced conformity within an enclosed structure.

Symbolic violence, meanwhile, is carried in language—its forms and associations. Like invisible prison walls, it can envelop us within its structure. When we analyse discourse we find more than the semantic content of the words: language can carry intent, emotive message, persuasive strategy, and so on. In this way language conveys an act or experience between speaker and audience.

Political speeches are often packed with psychologically persuasive mechanisms such as, in Britain, the classic three-word mantra: ‘Take back control’, ‘Strong and stable’, ‘Get Brexit done’. Their phraseology is simple and accessible and punches straight into the public’s insecurities. Additionally, politicians’ responses to in-depth enquiry are often loaded with tangential techniques to distract and nullify others’ lines of enquiry.

We must become adept at recognising violent acts that are projected through language if we are to subdue their impact. Awareness of symbolic violence, in the first instance, allows us to recognise instances where we might become trapped or constrained.

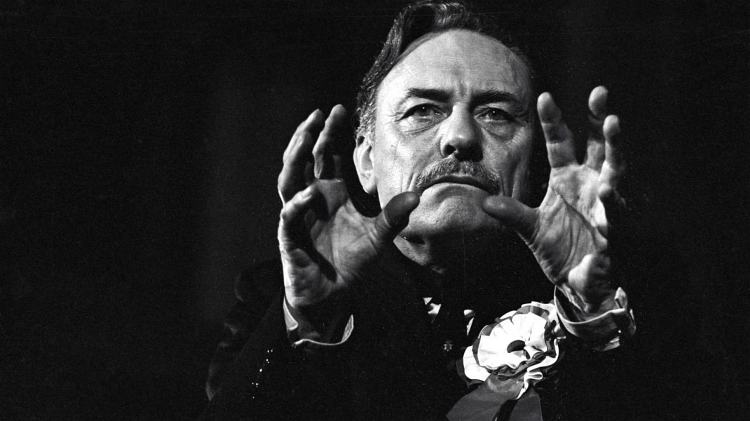

We often use language in speech to elicit emotive engagement and alignment with our discourse. Enoch Powell's 'Rivers of Blood' speech (pictured), delivered in 1968, is said to have stirred racial tensions. (Don McPhee)

Let us now consider a narrative of ‘invasion’ used to describe refugees crossing the channel; we can see how such discourse might position our thoughts and feelings with regards to those mentioned.

Compare the language of ‘invasion’ with a language of ‘investment’ used to refer to Jeff Bezos’ worldwide presence through his company. The associations of such choices of terminology reverberate across a simplistic binary separation of bad versus good, preying on moral norms whilst inviting associated emotional and behavioural responses.

Many instances of symbolic violence are glaringly present in news articles that reduce not only the individuals described in them but entire groups. For instance, a journalist may make a reference to the attire or the body of a female politician, which they would not direct towards a male politician. The formulation of such discourse and its associations constitute an act of profiling, feeding an economic agenda of selling news whilst side-lining the professionalism of giving an important political account. In furthering traditional gender roles, the journalist submits themselves to a structural and symbolic violence they merely re-enact.

The conflict between ethical journalism and propelling a news article into the limelight means that much symbolic violence becomes relished, used as an economic tactic that denigrates not only certain groups but ironically, the very writer of the article themselves. In selling a prejudicial, reductive account of the other they sell and reduce themselves. They become primarily an economically productive unit (to which other values must be relegated) within the contemporary societal system; they are what Foucault describes as ‘docile bodies.’ Docile is not to be confused with inaction; many forms of activity are exceedingly compliant. A docile body is one used to promote and enhance the societal agenda and norms in which it is embedded.

Systematic and symbolic violence are intricately linked. We can see how discourse can serve to profile or even exclude a group according to restrictive, derogatory narratives which endure as part of the structural narrative, becoming normalised into acceptance as a truth about the way things are.

Our relation to forms of violence

The popularity of symbolic violence warrants further exploration. After all, the success of such coverage depends on the public consumption of it. We cannot simply assign responsibility to the individual putting forward such accounts when so many people seek out and consume such material.

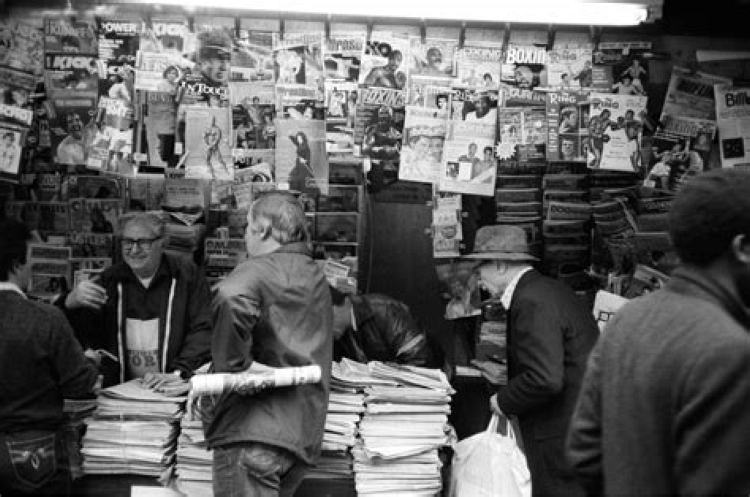

What is it that we seek out in the popular press? (Vaticanus)

Neither can we assume a simple causal direction from writer to reader. The writer or speaker may instead be the medium or channel for popular opinion.

Depictions of symbolic violence must serve some purpose. Perhaps we are related to violence by desire, whereby symbolic violence allows us to subvert violent impulses whilst maintaining a notion of ourselves as non-violent. Such accounts potentially serve as mirrors upon our internal conflict.

Perhaps there is some opportunity for catharsis in these external manifestations of violence—in allowing us to find temporary release from repressed emotions. Alternatively, we are infected by such material.

I suggest that both such processes are possible. If, for example, I feel a violent impulse towards my boss but think it unwise to express my issue through speaking directly with them, I might find temporary relief in attempting to satisfy this impulse by denigrating them to a colleague. My problem with my boss remains unsolved but an unsatisfactory, yet seemingly safer, outlet for my impulse gets set up which I can return to repeatedly. This toxic outlet can sit in me like an infection that rises up each time I sense an unrest in myself.

An important point here is that I may not be fully aware of these processes within myself or of any link between them. I can assuage to some extent a problematic violent tendency in myself which I have repressed and which bubbles up and seeks outlet. Even so, a satisfactory solution remains outstanding.

One of the first problems of violence, then, is a recognition not just of its forms but of our producing and partaking in them. To see violence only as elsewhere can constitute a denial that maintains the problem.

Our denial of this instinctual life is maintained by our desire to conform to notions of being morally good, to see ourselves as only good an attempt to expel that which we cannot admit to consciousness. Violence then needs to be recognised as a problem for all of us, one that necessitates expression of some kind. Repression and the return of repression is a cycling of the problem rather than a solution.

We see this happening on a societal level with the return of nationalism, fascism, and extremist politics. Repression offers but a temporary solution when there are less-toxic, more-healing, and life-affirming forms of release. As Aristotle believed, we can experience katharsis in an encounter with an artwork which allows us to moderate our emotions. In that case, it would seem we can turn to forms of art to manage forms of violence.

A flourishing culture harnesses violence

In the Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche offers us an account of how a successful culture can support its people in coping with existence, allowing for the safe expression of human impulses. In contrast, a declining culture fails to fulfil this functional role for this purpose. Nietzsche saw modern Europe as an example of the latter. He raises the question of how to remedy such a cultural decline. For comparison, Nietzsche offers Ancient Greece as an example of a flourishing culture.

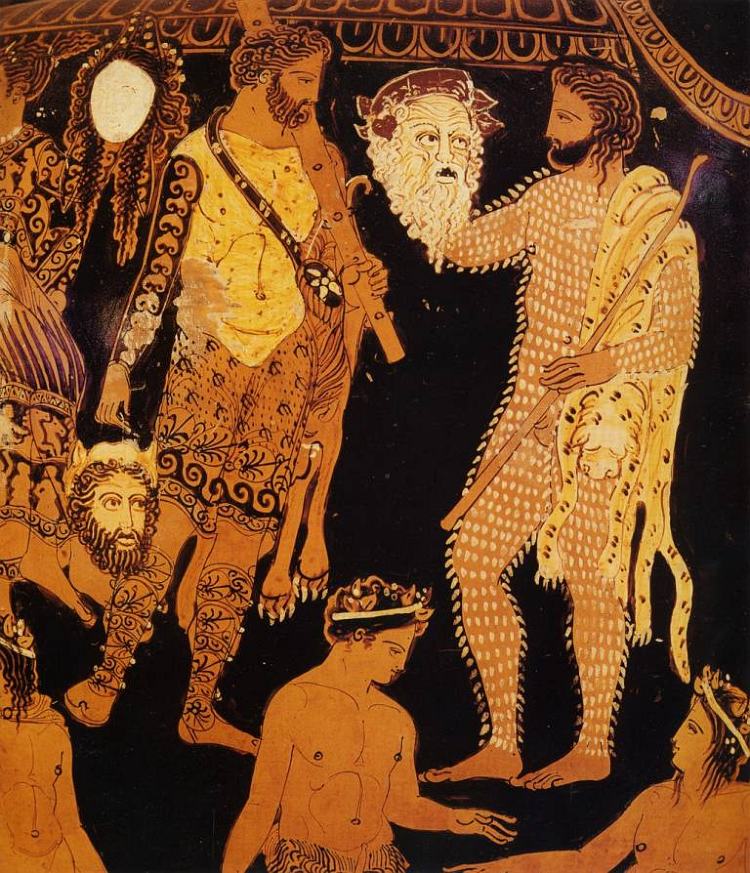

The Ancient Greek version of the Dionysian festival offers a safe mechanism for the release of powerful feelings, giving expression to human impulses that are often kept at bay or repressed. It does so via the creation and dramatic performance of a new art form, i.e. ‘Attic tragedy’.

Violence is expressed via dramatic performance. (Source)

The festival serves as a container, allowing for the repressed aspects of human experience to come to the fore whereby people participate in an intense, collective experience, transcending boundaries of the self and individual subjectivity. This dissolution of boundaries within the form of the festival allows for a release in defences, a surrender to life and its impulses, that revitalises rather than destroys.

The celebration, by offering an encounter beyond everyday norms and a safe transcendence of individuality and its associated defences, enables a reestablishment of harmony within the self and across the collective. As such, the Greek Dionysian festival is a life-affirming act, in contrast to the ancient barbaric Dionysian practices that were taking place elsewhere. The chaotic violence is instead harnessed in the Greek Dionysian festival before its destructive force is unleashed and expressed via symbolic, artistic form.

Further to a recognition of our violent tendencies and getting beyond a desire to see ourselves as virtuous, there is a way in which we can find a healthier expression of these impulses. A life-affirming expression is one which transmutes the impulse to destroy, exclude, or coerce the other into creative form. We can see contemporary examples of this in the artistic and sporting events that we flock to in a bid to engage in personal yet collective emotional journeys. Indeed, great sports people are thought to bring artform into their game. We are not simply spectators; we undergo experiences that bring some psychological equilibrium.

We can take Nietzsche’s highlighting of the mechanisms contained within the Ancient Greek Dionysian festival as a timeless message; he indicates that all societies must find ways to resolve the propensity to act out violence upon others.

The message I have taken from my philosophical and psychological examination of violence is that we cannot rid ourselves of what is a fundamental aspect of our existence. However, we can aim to attain a form of expression that does not destroy but instead affirms the human condition over and over in collective acts of artistic celebration.