Existence Is Uncertain Because Death Is Not

Featured image: Death Comes to the Table of the Miser (1638) by Giovanni Martinelli.

Certainty and uncertainty, like life and death, are inherently related. Death is certain in that it comes to everyone that lives at some point; it’s just its timing that is unknown. Such certainty brings with it the realisation that one will cease to have any control over any events in the real world after its happening. The anxiety and fear that this mortal realisation produces results in a pre-emptive strike against death by moving to ensure that life continues after it, even if that life is not your own.

I.

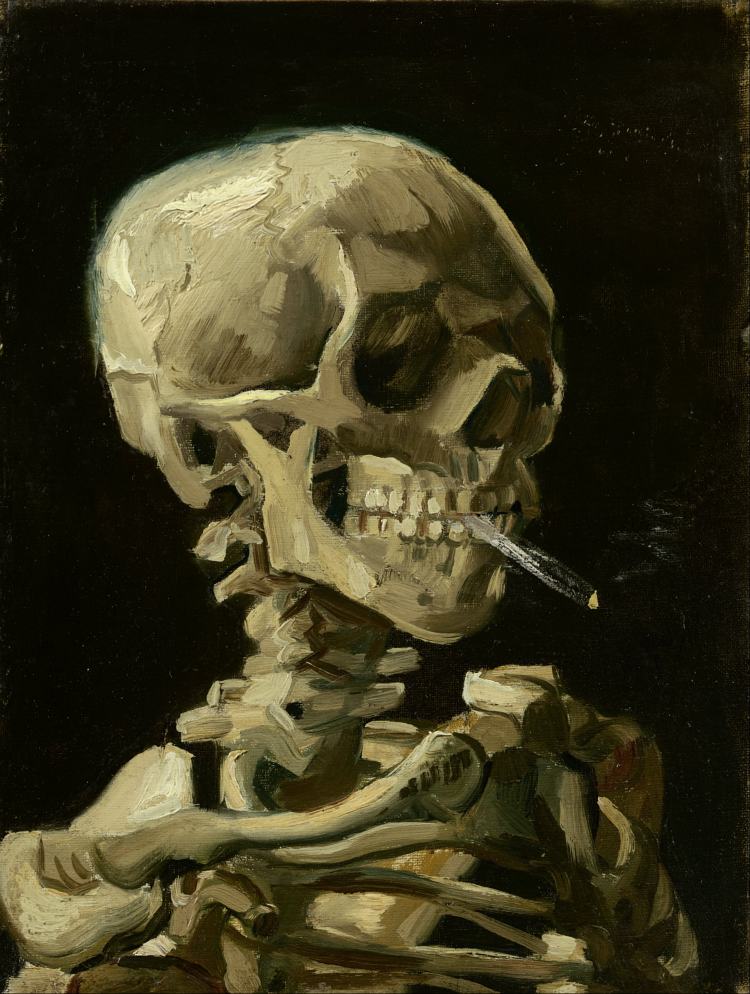

Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (1886) by Vincent van Gogh.

Death is, in fact, certain despite containing elements of uncertainty over the timing of its arrival.

There is that old adage, attributed to Benjamin Franklin, that ‘in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes’. The certainty of taxes is of no interest here. The certainty of the former, however, can often prompt an existential crisis in a person, be that in adolescence, when their youthful jouissance is cut short by the realisation of their own mortality (which, in my case, triggers forays into the internet universes of Tumblr, Reddit, Twitter and the like to express existential dread), or in the ‘middle’ of one’s life, whereupon mortality induces a quasi-messianic revelation that their time is indeed short and that they need do something about that now (divorce, lavish purchases and questionable new younger partners, likely in that order).

The realisation that death, in fact, comes to us all despite the juice cleanses, anti-wrinkle creams and workout regimes. Death is actually the one event that humanity universally experiences irrespective of differing identities or social positions. Death is inescapable.

However, despite death being life’s great known, it is rendered a great unknown, simply by virtue of one not being born with adequate notice of one’s death. The unknowability of death, or rather the uncertainty that it evokes in its omnipresence, is characteristic of humanity’s apprehension of the certainly uncertain void.

Jacques Derrida offers a treatment of the individuality of death in his work The Gift of Death (1995), in which he argues death to be a solitary event in which no other can be present. Considering this void that is, thus far, always possible, Derrida notes that

Thus, the individual both sees death coming and does not see it coming right up until it strikes; no person is able to identify when their time will come and yet is always sure it is coming. Life and death are always at the centre stage of existence’s theatre: they lock horns, one dodges the other, they trade blows, inflicting wounds, winning, triumphing, and until eventually one loses—the loser is always life. The life-death relationship is much like that of the intruder and the nightwatchman: the former hides around the corner with bated breath as each foot of the nightwatchman falls one after the other until the beam of his torch falls squarely onto the intruder’s face. At the point where the nightwatchman finally comes to the intruder it is, in fact, death coming to life, his looming presence was expected at some time or another but specifically when he was to emerge remained unknown until it wasn’t anymore, until the torch’s blinding illumination.

Returning to Derrida, he states that

Derrida’s conception of death here, strangely, makes one out to be special, to be one-of-a-kind in death’s eyes, in the sense that each person has their own death. When talking about war or genocide the emphasis is placed on its scale, on the mass element of death, and yet each death is special in that it is particular to that individual. One’s demise is one’s own: it is not something that another ‘can undergo or confront in my place’, and, therefore, we know it’s coming for us; everybody knows that they will meet their own particular death. For this there can be nothing other than certainty.

II.

Having prepared the ground of death-as-a-certainty, I will now turn from an analysis of Derrida’s work to one of Lee Edelman’s work and the key concepts of the latter in No Future (2004). Edelman outlines the concept ‘reproductive futurism’ (Edelman, 2004, p. 2): the reproductive basis of any society with a future. Edelman highlights how humankind’s broad response to the certainty of death is life, i.e., humans produce more humans so as to sure up the uncertainty of society’s continuation, for each member will face their own death and so fight the end with more new beginnings. The culmination of all the above is the reassertion of reproduction’s pre-emptive response to the certainty of death.

The picture that certain death paints is a bleak one: it’s not something you’ll find as a line in a schoolbook or a cheery Christmas carol. Moreover, the certainty of death breeds an often-insidious sibling: uncertainty.

This uncertainty extends beyond solely not knowing when death is coming but, perhaps more importantly, not knowing what transpires in post-mortem society. By ‘post-mortem’ I do not mean the afterlife: I mean the following scenes to be played out on the world’s stage one has just exited; I mean the impact of one’s life. It is the feeling that one needs to leave a mark, to have a legacy, to let the ‘world’ know that I existed.

This explains the need to prove that one lived, even after they cease, to see grand monuments being built, or gargantuan buildings being erected in their honour, or the naming and renaming of landmarks by others deemed ‘worthy’ enough. But the most-lasting effect had by this need to mark or quell post-mortem uncertainty is not tangible but rather attitudinal: it is the creation of what Edelman calls ‘reproductive futurism’, which is a desire for permanent continuation via the constant reproductive capacity of heterosexuals within the human race. In short, society is based on children.

Reproduction sures up society and society sures up reproduction, forming an infinitely regressive chain of bodies that serves only to populate and carry ancestral memory. Edelman remarks:

Thus, the future is a fantasy. It is uncertain. It is unclear what form or shape it will take. By inserting reproduction into the fundamental elements of societal formation humanity has attempted to take out some risk: it has attempted to make reproduction more certain by creating a narrative of necessity. The drive to live, or life-drive, has come to characterise human society simply by the fact that we are so afraid of death.

To return to the analogy of the intruder and the nightwatchman, rather than run the risk of there being only one intruder who, when discovered by the nightwatchman, will render the game of life well and truly up, there is instead a long ancestral line of intruders who lie in wait and continue the trespass unto this mortal coil.

Taking Edelman’s idea of reproductive futurism, it becomes clear that reproduction is, in fact, a shaky, uncertain crutch constructed to make abject uncertainty feel less so, to make death not the final end but a momentary one. Thanks to reproductive futurism, when I meet my end my bloodline will not. Society will be survived by the children. Ironically, then, reproduction becomes a form of replaceability—ironic because I do not continue.

‘Death is very much that which nobody else can undergo or confront in my place’ (p. 41) but this is not the case for life. Offspring can undertake the continuity of the parental life cut short by death: continue where their parent left off. Death makes an individual special or particular. Life does not.

Alive I am nothing; in death I am something. Death’s certainty is the cool embrace of validation, no longer racked by the fear of what if and when. It is the cessation of mortal being that meets us all. And under the framework of reproductive futurism we can slip into eternal sleep for the first and last time with the reassuring knowledge that the ‘we’ continues even after the ‘I’ has stopped.

However, not every person can or does reproduce. For Edelman, there is a class of (Queer) persons, which he labels ‘sinthomosexuals’ (p. 48), who are the ultimate aliens of heterosexual society. The sinthomosexuals are, for Edelman, those Queers who do not engage in society’s reproductive futurity by having any offspring.

Setting aside Edelman’s theory that the non-compliance of sinthomosexuals with reproductive futurity makes them a threat to the heteronormative society’s need for ‘futurity’, the reproductive decisions of these Queers make life more uncertain for them. By deciding not to participate in society along its heteronormative lines sinthomosexuals will not replace themselves with offspring, will not move to sure up society’s future, will not try to combat uncertainty with the certainty that the Child offers with its new beginning. Instead, sinthomosexuals interact only with the jouissance mortality: they begin and end with themselves.

III.

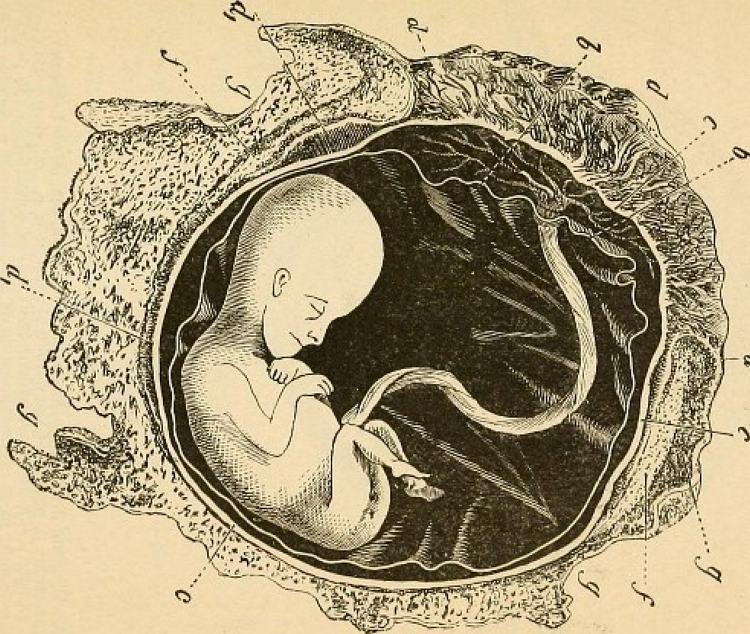

An image from a Hahnemann Medical College yearbook (c. 1910).

In sum, we can be sure of death. The fact it eventually comes is not a surprise. It is unfortunate that one is not born with this awareness because when mortality makes itself known, at one time or another, it is jarring and can trigger a sequence of additional traumas that can mark the road to the end with additional suffering.

However, death meets every individual at the door of mortality and each person must face it alone as ‘nobody else can undergo or confront [it] in my place’. Because of this certainty the events that follow death are made all the more uncertain—how those that continue on living remember you, how society functions in your permanent absence, how the world turns without you.

What is, however, even more uncertain is whether any events are even to follow at all. The uncertainty that the lives of others continue after one’s own death escalates the death-anxiety one feels throughout one’s life. As a response, some focus on the idea of reproductive futurism, that simply by reproducing one makes the realisation of a future all the less risky, all the more certain. Along these lines they attempt to pre-empt the cessation of future input by reacting to the footfall of the nightwatchman before he’s even turned the corner. Even so, a child can itself never be certain of the future because it too will be racked by the same existential issues I have outlined here.

Alternatively, one might—were they to be one of the sinthomosexuals—engage in the most certainly uncertain act of all: to be mortal without the reassurance of an offspring-cum-anointed-successor. In this case the certainty of death produces an ultimately uncertain post-mortem life because, when dead, one ceases to have any input into life at all (presuming the non-existence of the spiritual afterlife).

The solution to uncertainty, I propose, is to lean into it, to bring society to a close with a final curtain: no more life; only death. By rallying behind mortality humanity will have to face only one uncertainty: the time and date of Death’s arrival at the miser’s table. Living with the certainty of an uncertainly timed death is manageable and it engenders solace and solidarity in the dwindling few who still live.